Alan Hunter, one of the original VJs during the first years of MTV, is a very close personal friend of mine.

Or at least, that's how it always seemed. I mean, we go way back. He was in my house practically every day when I was a teenager. I looked up to him. He was a key source of company, he helped me forget the drudgery of the school day and he turned me on to a lot of music.

The fact that I was a teenager in small-town Missouri and that Alan Hunter was a television personality in New York who had never heard of me did little to lessen our bond.

When MTV debuted in 1981, the moment video killed the radio star, Hunter was the first VJ to appear on the network. Of the original five VJs — Hunter, Martha Quinn, Mark Goodman, Nina Blackwood and J.J. Jackson — Hunter was my favorite. So I hung out with him the most.

Each of the five VJs was also an archetype, as though picked from central casting, like a video-jukebox Breakfast Club: Martha, the girl next door; Nina, the rock vamp; Mark, the jock; J.J., the elder statesmen. And Alan?

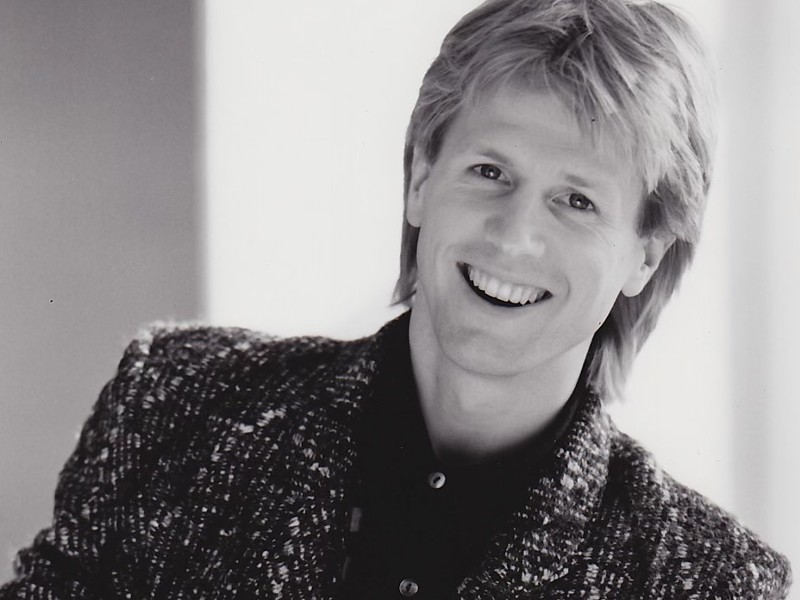

Alan was the lovable goofball, a jovial, blond-mulleted everyguy who talked with a warm amiability, a comic physicality and a unique blend of telegenic polish and parodic irony. Of the five VJs, it was Hunter who most established the standard VJ aesthetic — informal accessibility, sharp speechcraft, cool whippersnappery — that was as new to television hosts as was the music-video format itself.

Hunter was not a rock expert like Jackson, a radio legend who helped break Led Zeppelin in America, or Goodman, a seasoned disc jockey from the biggest rock stations in Philly and NY. But what Hunter lacked in musical expertise, he made up for in Cronkitean trustability and easy charm.

I wanted my MTV. All the time. The way kids come home from school today and transform into video game zombies, I got lost for hours in the music videos ushered in by Hunter. I felt like I was hanging out with a cool older neighbor kid who brought his Tom Petty and ZZ Top records over. I came for the U2, the Madonna, the Whitesnake; I stayed for the Alan Hunter.

So imagine my surprise when I heard that Hunter is now living in St. Louis. My old buddy lives here! I was floored to discover that Hunter's SiriusXM radio shows broadcast from his home in Webster Groves.

I wasted no time in tracking him down, and Hunter agreed to meet me at a pub in Webster.

As I arrive for our big reunion, I realize that I had not laid eyes on my old pal in decades. When I watched him on MTV, he was in his 20s. Now he's 65. Would I recognize him?

Then, through the door walks Alan Hunter. Wearing a blue puffer jacket and jeans, Hunter approaches me with much the same youthful countenance as I remember, his blond hair a little darker, his downturned eyes now behind glasses.

"How ya doin'?" he asks — as though this is in fact a reunion of old friends. I immediately feel as if he is about to pull out a microphone and point it at me à la his old MTV spring break segments. But amid the clatter and laughter of afternoon drinkers, we snag two pints and a table, and I ask him about the things I always wanted to know.

We discuss his early bio: Hunter grew up in Alabama, attended college in Mississippi where he met his first wife and, in 1980, struck out for New York to become an actor. He landed minuscule roles in Annie (the Carol Burnett one) and David Bowie's video for "Fashion," but the kind of Broadway roles he wanted eluded him.

As he recounts these events, Hunter is quick with details when I ask where he lived ("55th and Broadway in a little one-bedroom apartment for $550 a month"), where he tended bar ("The Magic Pan at 57th and 6th") and what he thought of the city then ("In 1980, New York was in the toilet").

In June 1981, Hunter had a chance encounter in Central Park with a TV producer named Bob Pittman who was starting a new cable channel that would show music videos around the clock. "I said, 'That's funny — I was just in a David Bowie video. Good luck with your channel,'" Hunter says, adding that he thought nothing more about it. Two days later the phone rang.

"They brought me in to audition at the studio at 33rd and 10th in Hell's Kitchen," Hunter says. "Being an actor, I needed a role. They said, 'Be yourself.' And I said, 'Who's that?' So I thought I sucked. But they had me back three more times in three successive days."

Hunter was the last of the five VJs to be hired, and a month later he was on the air. If he was unsure how to do the job, he was not alone. "MTV was put together by duct tape and tons of people who didn't know what the hell they were doing," he says. "It was a 50-ring circus. Total chaos. Things would change every day. I would come in, and the set would be moved around. They were constantly experimenting."

What of Hunter's signature look with the feathered hair, the suspenders, the vests? "When I got hired, they gave me an envelope on the first day with 500 dollars cash in it and told me to go buy some clothes," he says, noting that MTV had no makeup or wardrobe staff. "So my wife and I went to Macy's and bought some clothes on sale."

As I ask more questions about the behind-the-scenes production of live television, Hunter drops a bomb: "Well, MTV was never live."

Wait. What? Alan, Mark and Martha were not talking to me in real time? I admit that I always thought his video intros were live, as if this new information was some sort of betrayal. "Sorry to take some of the luster off for you," Hunter laughs. "All of our breaks were pre-recorded a day in advance. I would do my five-hour shift in an hour and a half."

I also get my old amigo to reveal his VJ salary that first year: a cool $28,000. "That wage was a little bit better than a chorus guy on Broadway, which was my yardstick at the time," Hunter says. He even kept his bartending job for a while after he started VJing, unsure as he was about MTV's future.

Hunter says he had no idea that MTV was going to be a success, noting the channel was losing money. Moreover, Hunter had no sense of the network's cultural impact early on, as MTV was not broadcast in Manhattan for its first year of existence.

Then, after a few months, MTV sent its VJs to make promotional appearances across the country, and Hunter realized something big was happening. "They would send me to a record store in Little Rock or Grand Rapids or somewhere and a thousand people would show up," Hunter remembers. "I would say, 'What are all these people doing here?' And they would say, 'They're here to see you.'"

Hunter hit it off right away with Quinn and Blackwood but not Goodman. "He thought I was a nerd, and I thought he was an asshole," Hunter says.

Later, they became close, but the early friction came as Goodman's music snobbery clashed with Hunter's casual fandom. "My schtick was less about being some music journalist and more about being a fun guy messing with regular folks," Hunter says. "They eventually started having me do man-on-the-street stuff and going on trips to cover spring breaks and other things."

The Hunter-hosted trip I most remember is MTV's Hedonism Weekend in Jamaica with Bon Jovi in 1987, a wild hair-metal beach party with the world's hottest rock band and a smorgasbord of booze and bikini-clad girls. I had to ask Hunter — with such immediate access to Bon Jovi-level sex, drugs and rock & roll — how much did he himself partake?

"Did I party? Oh god, yes," Hunter says. "But I was happily married at the time, and I have a pretty strong willpower. That doesn't mean that when it's three in the morning and I'm partying with everyone that I'm not struggling to try to not do another line of coke. But you have to show some professionalism. I wasn't going to screw up my job."

While Hunter says he was never about serious music journalism, he was nonetheless at the center of some history-making musical events, including Live Aid and Billy Joel's groundbreaking concert in the Soviet Union. At Live Aid, Hunter was given the tough task of interviewing the members of Led Zeppelin just after their infamously maligned reunion performance. "The whole scene was so chaotic, that about all I could get out was, 'What was that like?'" Hunter recalls. "But overall it was 17 hours of standing in awe of everything that was going on."

Hunter's talent for conversational spontaneity led to road shows such as Amuck in America, which saw Hunter traveling across the country interacting with locals, a ratings boom that precipitated MTV's eventual pivot from music videos to reality shows. Ironically, the changes that Hunter helped initiate roughly coincided with his 1987 decision to leave the network.

"Burnout was high, and I felt like I should leave while I was on top," Hunter says. "So I chose not to exercise the last two years of my contract. In hindsight, I should have stayed longer."

Hunter moved to Los Angeles, looking to fulfill his old dream of being an actor, only to find that path blocked by his success as a VJ. "I would go to auditions, and they would be, 'Hey, it's Alan Hunter from MTV,'" he says. "What I didn't understand is that I had played 'me' for six years. It's very difficult to change that."

Still, Hunter forged a successful path in entertainment on the other side of the camera. In his hometown of Birmingham, he started Hunter Films, was nominated for an Oscar in 2004 for producing the short film Johnny Flynton, built a multi-use entertainment facility and co-founded the acclaimed Sidewalk Film Festival.

Several years ago, while planning Sidewalk, Hunter, then divorced from his first wife, received an email from a female film executive in New York. "She said, 'Your high school girlfriend's older sister's daughter is my first cousin's roommate,'" Hunter says with a laugh. She was interested in teaching a film workshop in the festival.

That email eventually led to a second-time-around family for Hunter. His wife, Elizabeth, became a pioneer in the world of digitally augmented reality and experiential theater, and Hunter started hosting shows on two of SiriusXM's most popular channels (80s on 8, Classic Rewind) six days a week from his home office. (Brace yourself: Those aren't live either.)

Then, in late 2021, Elizabeth accepted a position at Washington University, and the Hunters relocated to St. Louis. And we're caught up.

After a thorough 90-minute walk down memory lane, Hunter is due to pick up one of his kids from a class. "Let's talk again," he tells me.

Strolling alone out of the pub, unbeknown to the patrons around him, goes a pioneer who was at the tip of the spear of a music and cultural revolution, and is a seminal figure to a generation raised on MTV. And, also, is a very close personal friend of mine.

This story has been updated.

Follow us: Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter