Here's one thing anyone who knew Bob Cassilly will agree on: Cassilly, whose body was found yesterday morning in a bulldozer at Cementland, his larger-than-life sculpture museum/creative experiment, died the way he lived, building something unlike anything else the world had ever seen.

"He was out there working every day," recalls Bill Streeter, a video artist and friend of Cassilly's. "It was his favorite thing to do."

And here's another thing anyone who knew Cassilly or visited the City Museum can agree on: There will never be anyone else like him.

"That a single mind has the whimsy to conceive something like that, and the muscle to make it happen," marvels Matt Strauss, founder of White Flag Projects. "That's singular."

"He really put St. Louis on the map as far as being creative goes," says Barbara Geisman, the city's former executive director of development, whose friendship with Cassilly stretches back to the 1970s when they were among the first urban pioneers to settle in Lafayette Square. (Geisman and her partner, PR maven Richard Callow, later moved into the City Museum building.) "The City Museum got people to come downtown who wouldn't ordinarily be near here. It made them realize there's more to downtown than a baseball stadium."

Before he became a builder, Cassilly was a sculptor. He worked mostly in concrete, though Geisman also recalls him using the wood left over from the renovations of his house in Lafayette Square to create dragons in empty lots. He populated Forest Park with baboons, a hippopotamus, Marlin Perkins and the giant turtles in Turtle Park. He also made a surprisingly ethereal monarch butterfly for the Butterfly House in Chesterfield.

But his most lasting achievement will undoubtedly remain the City Museum, an urban wonderland of caves and five-story slides and an enormous jungle gym that also encompasses a circus, a surprisingly sober display of some of St. Louis's discarded architectural treasures and a shoelace factory, an homage to the building's earlier incarnation as the International Shoe Factory.

"We closed on the building on June 21, 1993," recalls Tim Tucker, who left his position with the Missouri Department of Mental Health to go work for Cassilly. "I told Bob to buy the smallest building on Washington Avenue because everyone else who had tried to build there had gone broke. He said, 'I bought the International Building.' I said, 'Bob, that's the biggest building on Washington Ave!' That was when 'city' was a four-letter word. Bob negotiated with Washington University to lower the price from $2.5 million to $525,000. Back then, if you gave anyone with any sanity half a million dollars, they would not spend it on Washington Avenue. But Bob said, 'For 69 cents a square foot, you can't go wrong.'"

From the start, the City Museum was destined to be both a work of art and a grand improvisation. The first piece Cassilly constructed, the serpentine wall in the parking lot, won a Concrete Council Award. But just hours before the museum was scheduled to open in 1997, Geisman and Callow were downstairs, pounding nails.

Even after he started work on Cementland, Cassilly continued to tinker with the City Museum, building more slides and installing trees and the world's largest pencil. "As long as there was available space," says Mike DeFilippo, who once served as the City Museum's resident photographer (and also, at one point, the Riverfront Times' staff photographer), "Bob would build something new."

For St. Louisans, the City Museum was a place they could be proud to take out-of-town guests. "Everyone who comes here, even the New York Times, thinks it's a special place, the likes of which will not be found anywhere else," says Geisman. "It's a tribute to Bob's willingness to try anything. He didn't sit around worrying. He was going to try and make it all work."

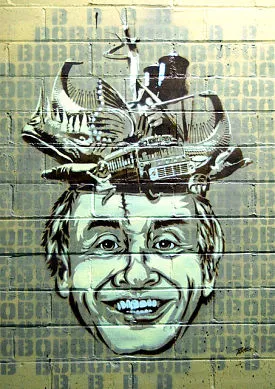

For local artists, Cassilly was an inspiration. "I moved back here from Chicago, and I wondered if I'd ever be able to stay here," recalls Peat Wollaeger, a street artist. (You can see some of his work on the new and improved South Grand Boulevard.) "But things like the City Museum kept me here. It inspired me, made me think, why not do something like that here and make St. Louis a better place?"

Cassilly hired young artists such as Stan Chisholm and Ryan Frank to paint murals inside the City Museum; another artist, Angela Perry, works there now in the children's art area.

It wasn't just young artists who felt a special loyalty to Cassilly. So did his team of workers, the "Cassilly Crew," many of whom had been with him for 30 or 40 years. "They were his real family," says Tucker.

Adds DeFilippo, "So many employees depended on him for their work and their livelihood and even their identity." They stayed with Cassilly even though they could have earned more money working elsewhere. But, says DeFilippo, "if you had a choice between building a rest stop or building something like the City Museum, to see a child playing on your creation, which would you do?"