At the turn of the twentieth century, Reedy's Mirror was one of the most important literary journals in America and abroad. William Reedy, its editor, was the "Literary Boss of the Middle West" and a St. Louis playboy. He once partied so hard that he woke up married to the owner of his favorite brothel.

In those World's Fair days with trolley cars and steamboats, when St. Louis was the fourth largest city in the U.S. and growing, Reedy did things his way. He mingled with Oscar Wilde and called poet Ezra Pound and anarchist Emma Goldman friends. Reedy's Mirror took risks publishing no-name writers like Emily Dickinson, James Joyce and St. Louis' own Kate Chopin, ushering in a new literary era called, roughly, modernism. The poet Orrick Johns wrote that "Reedy was the only figure to give St. Louis a literary character in the eyes of the rest of the country between 1900 and 1920."

But Reedy, excommunicated and controversial, paid a price for his iconoclasm. Much of St. Louis found him "hopelessly depraved," writes Max Putzel in The Man in the Mirror: William Marion Reedy and His Magazine, a thorough literary biography published in 1963.

Reedy, however, wore his mantle of controversy lightly and stayed in the Midwest even when moving to the East Coast could have possibly reduced his infamy and broadened his influence. Often, it feels like New York is the only place for capital-L Literature. But for a time, if you wanted to make it as a writer, you needed to travel west to St. Louis, at the far edge of the country, and convince William Marion Reedy to publish your work in his Mirror.

Reedy was born in December 1862 at the start of the Civil War. He was raised in the Irish neighborhood of Kerry Patch, north of downtown, and grew up a child of Reconstruction.

His father, Patrick Reedy, was a cop in their home district, also known as the "Bloody Third." If Patrick had a dispute with a fellow Irishman, "a policeman was expected to lay aside coat and weapons on occasion and fight the Irish with his bare knuckles," Putzel writes.

The younger Reedy attended the leading Catholic prep school of the time, Christian Brothers College, but got mediocre grades, graduating with a business certificate. "This fact always struck Reedy and his friends as exquisitely ironic," according to Putzel, "for his life thereafter was one long financial emergency and he never gave up reading Greek and Latin poetry."

Patrick Reedy found a newspaper job for his son after he graduated from Saint Louis University. As the youngest reporter for the Missouri Republican — which was sympathetic to the Confederacy — William Reedy first made his name covering a fistfight between a priest and schoolmaster in Carondelet. He moved up in the newsroom to cover more gruesome events, such as hangings at the Four Courts building. Reedy estimated he witnessed around twenty. "Reporters and jailers would march their victim out to face the crowd and gallows," Putzel writes, "and Reedy would note how [the prisoner] glanced up at the sky, or at a bird perched on a tower, and then look straight ahead with 'fluttering swallowings in his throat.'"

One night, two of Reedy's CBC buddies broke out of jail, and a patrolman Reedy knew shot one of them dead. "Shea was very much like me," Reedy wrote of his friend, "and had a natural right to as much as I have had of the world."

Later Reedy wrote for the St. Louis Globe-Democrat. One possibly apocryphal story is that Joseph B. McCullagh, the paper's owner, gave Reedy his first assignment to go to Forest Park every Sunday for a year. Reedy's Monday column, "Sunday in Forest Park," showcased his early talent as a critic and essayist.

Reedy was supposedly also fired from the Globe-Democrat and went to McCullagh to get his job back. When he was successful, he promised to report for work the next day.

"But Reedy failed to appear," recounts the Kansas City Star. "And when McCullagh met him in the lobby of the old Southern hotel and asked the reason, Reedy waved the editor aside with a lordly air and said, 'I have decided to dispense with your employment.'"

Journalism was not Reedy's only interest. He enjoyed art and literature and was a regular at the public library. "Only the man who built the collection knew it better than Reedy," a librarian remarked at the time.

"Literature," Reedy said, was the "common dream" of him and fellow young reporters, but these aspirations felt "foredoomed." America had yet to produce a true literary movement.

Reedy got a chance to show his own literary acumen when he was just twenty years old. In 1882, Oscar Wilde visited St. Louis on a well-publicized tour of America. The Post-Dispatch greeted the Irish writer by running a cartoon of Wilde as an ape. The Globe-Democrat described him as "a dandy in a fur overcoat." Reedy's Missouri Republican interview was one of the only columns to recognize Wilde's greatness.

Oscar Wilde's work is a high-water mark in this literary period. "[Wilde] was a Man of Feeling tainted by progress and materialism," Putzel writes, "jaded, disillusioned, and content to be corrupt because he was helpless to stem the spread of corruption around him." The same was true of Reedy, who complained about corruption but was offended if his bribes weren't taken. Both writers were also known for their witticisims and were fans of the poet Walt Whitman. "Do I contradict myself?" Whitman asks in his epic "Song of Myself." "Very well then I contradict myself, (I am large, I contain multitudes.)"

After Wilde was outed as a homosexual, many called for his plays to drop his name from the credits. Reedy was indignant. By then, April 1897, Reedy was editing the Mirror and, in an essay, described Wilde's plays as the "brightest comedies of the century ... constructed with a skill beyond the attainment of any contemporary."

This open-mindedness would characterize Reedy throughout his career. "I don't know what party ticket he votes, if any, and I don't care," wrote Bert Love in the Tulsa Democrat. "I don't know what church he prefers above others, if any, and don't care. I don't know whether he eats caviar or Boston beans for breakfast, and I don't care. I do happen to know, however, that he despises pajamas, whilst I secretly adore them! What matter? The good in Reedy is his intellectual honesty, his large-hearted human kindliness, [and] his civic-ethical stand pattism as he conceives it."

Reedy lasted four years as a reporter before striking out into ward politics. He hoped to be appointed commissioner of parks, but wound up back in journalism, starting a "journal of society" with a business partner.

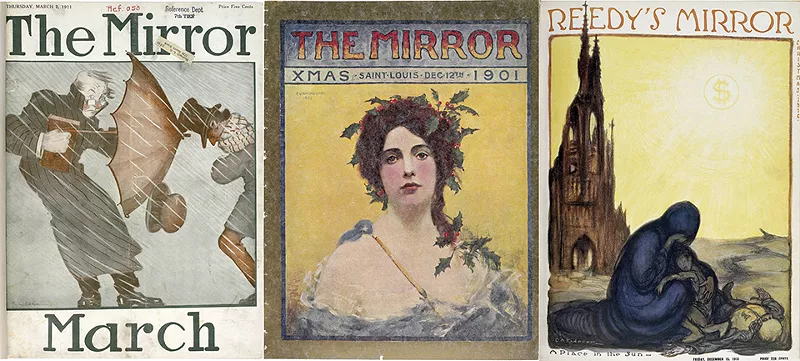

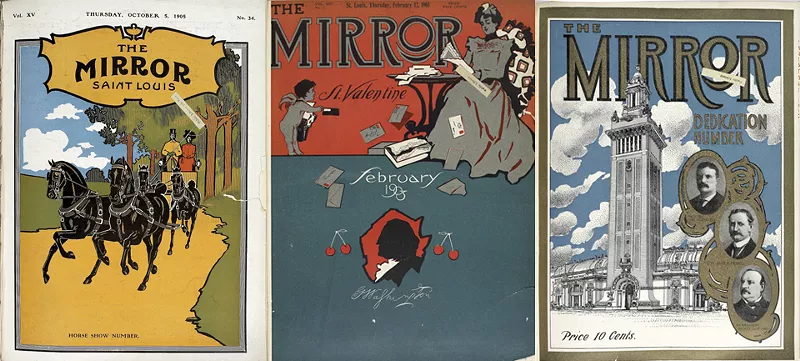

Town Topics was a gossip rag publishing "saunterings," poems and news of club openings alongside Reedy's essays. It was profitable based on blackmail; something Reedy called a "peculiar commercialism." (Prominent people would pay the paper not to print certain scandals.) Town Topics became the Sunday Mirror, and the Sunday Mirror became Reedy's Mirror when his business partner dropped out in 1892. With a 30-year-old Reedy at the helm, the Mirror moved away from journalism toward literature and poetry.

Around this time, "in the course of a prolonged debauch," according to Max Putzel, Reedy woke up hung-over and married to Addie Baldwin, the operator of a notorious St. Louis "pleasure resort" called the White Castle, which has nothing to do with the burger joint. From 1870 to 1879, brothels were legal if licensed in St. Louis, but soundly illegal by the 1890s.

If this is the same Addie Baldwin from an 1897 news account, then she was "a stout muscular woman, capable of whipping an ordinary man without using weapons." (The article is about an Addie Baldwin who was accused of stealing money from a horse dealer. She lived in a house that entertained men, let them sleep over and had many other female occupants, but the article didn't call it a brothel.)

Baldwin is said to have paid for Reedy's treatment for alcoholism shortly after the wedding. Reedy received the much-advertised "Keeley Cure," which included mysterious injections and tonics and was performed by a priest. The first printing of the Mirror began shortly after, and Reedy estranged himself from Baldwin. "Tell her to go back where she belongs," he told his business manager.

This first coupling would complicate his second marriage to Miss Eulailie Bauduy in 1897. Due to his being married and the Catholic Church not recognizing his divorce, Reedy did not get permission from Bauduy's parents to marry her. Eventually, the couple eloped and Bauduy's parents didn't attend the ceremony, which might have been for the best. Since Reedy was not allowed to marry again, all who participated in the ceremony excommunicated themselves "without necessitating any formal declaration of the fact by the church," according to one report at the time.

"The step was taken with full knowledge of what it involved," Reedy told the Post-Dispatch, in an article with the headline "Mr. Reedy Isn't a Bit Worried." The reporter described Reedy, who spent his honeymoon at the Planter's Hotel with his wife, as having "a satisfied and happy air."

"What the attitude of [my wife's parents] will be hereafter I do not know," Reedy said. "The church court says we are not married, but the hotel register over there says we are, and that is about the situation."

Reedy clashed with St. Louis' anti-divorce archbishop, John Joseph Kain — a major reason his annulment was denied. When asked about Reedy's new marriage, Kain replied: "They have never been married, according to the rites of the church."

The marriage shenanigans were just some of the many local rumors Reedy let spread. Putzel writes that "when a rival editor sent him the proofs of a scurrilous article about himself, probably intending blackmail, Reedy offered to fill in the scandals that had been omitted."

By 1898, the Mirror was receiving national attention, in part for Reedy's opinion pieces called "reflections" (in the mirror, get it?). He wrote in opposition to the Spanish-American War and other political follies. Especially during the war, popularity soared and the Mirror outsold the Nation and the Atlantic.

Reedy even printed critiques of his hometown. William Allen White's article "What's the Matter with St. Louis?" argued that wealthy leaders had let St. Louis become a "bloated village." Reedy himself speculated that St. Louis would not get the World's Fair.

The Mirror also benefited from Reedy's reputation as a literary genius. He was known for spotting the "primitive stirrings of naturalism" in American fiction. But Reedy didn't arrive at this conclusion on his own. Many female artists and thinkers, such as Sara Teasdale and Thekla Bernays, pushed Reedy's tastes towards naturalism, away from the stodgy Victorian verse of the last century.

In 1914, the first lines of what would become Spoon River Anthology appeared in Reedy's Mirror. This work by Edgar Lee Masters is perhaps Reedy's most important find — a collection of short free-verse poems that narrate the epitaphs of fictional small-town residents. Spoon River is the river near Masters' hometown of Lewistown, Illinois. The poems sought to demystify rural American life while creating an unabashed tapestry of the community. "At last!" Ezra Pound wrote of the poems. "At last America has discovered a poet."

T.S. Eliot, meanwhile, was famously ashamed of St. Louis. He claimed he never saw the Mirror, but there's no way that's true. Reedy's publication, in return, took little note of the poet, only mentioning Eliot's Harvard ode in 1910.

In early 1900, Reedy's second wife died of heart disease before the age of 30. Reedy was heartbroken. An obituary ran in the Mirror, and Reedy rarely discussed his wife's death, opting for a cheery mask at the parties he attended. "It gives me great pleasure to find myself in this large and distinguished gathering," Reedy would say, having become famous for after-dinner toasts. "I am large, and you are distinguished."

The man liked to eat and drink — with both poets and presidents. Reedy became so influential that he traveled to Washington, to dine with President Theodore Roosevelt. On his way home one evening, Reedy received an angry letter from Captain Asbury of Higginsville, Missouri, canceling his subscription to the Mirror because Reedy defended the president for "entertaining a Negro at his table." The man in question was Booker T. Washington.

Max Putzel notes that the editor "had grown up sharing the racial prejudices of the South." Of Washington, Reedy said: "If the South is insulted because a man of brains and character and philanthropic educational achievement is shown the respect due these high things, then the South prefers barbarism to civilization."

Reedy responded to Captain Asbury's angry letter in the Mirror, stating he had a nice luncheon at the White House, and he pointed out that a dog was also present at the presidential board. Putzel, who released his biography of Reedy 59 years ago, takes this mocking response as evidence of Reedy "outgrowing all racial prejudice." While Reedy was open-minded for his time, his joke doesn't work. It lowers the humanity of Washington to the level of an animal, demonstrating how white society men like Reedy could create Jim Crow standards, even while attempting a woke clap-back.

The Mirror was always booming and busting. In 1894, Reedy had to put the paper up for auction to satisfy his creditors, and his friend bought it, returning it to Reedy with enough working capital to keep it in business.

According to some, Reedy was poor because he was honest. "His poverty is a proud poverty," wrote a friend. "Most men of intellectual acumen plus honesty are poor in shekels, though rich in satisfaction." The truth is more likely that Reedy was just bad with money, particularly given his vices. (But there was also a rumor, later in his life, that Reedy turned down a job with famous publisher William Randolph Hearst that would have paid $50,000 a year in favor of intellectual integrity.)

In 1907, Reedy's Mirror nearly went bankrupt again, and Reedy retreated into hard drinking — but was bailed out by his mistress, Margie Rhodes. Rhodes owned a brothel where Reedy was said to have his own room, which he used to "accommodate distinguished visitors to the World's Fair."

For a while, a 40-year-old Reedy chased an eighteen-year-old Zoe Akins. Akins was a friend of the St. Louis lyric poet Sara Teasdale and would go on to become a Pulitzer Prize–winning playwright. She ultimately spurned Reedy's advances.

Eventually, Reedy married Rhodes, making two of his three wives brothel owners. The couple retreated from the city to a 28-acre farm called Clonmel, Irish for "vale of honey." Reedy continued as editor of the Mirror. In 1910, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch did a lengthy story about Reedy on his farm.

"Farming is a delightful occupation if you are a multimillionaire or have nothing else to do," Reedy said. "Otherwise it does not pay."

Reedy described himself as "farming by ink pot" — that is, hiring farm hands to work while he managed the books.

"Since I have been farming, I have had enough farm hands to organize the Ancient Order of Clonmel Hired Hands, with all the 'past grands' and 'exalteds' and 'supremes' necessary to success," he said.

The farm was quite labor intensive, with cows, a bull, hens, "somnolent sows," hogs, horses, a collie and a donkey. But Reedy had hired so many farm hands because he kept finding terrible ones. Much of the article is about all of the ways the farm hands failed.

"I remember one chap who did almost nothing except read The Country Gentleman, and suggest tools and plantations and improvements that averaged about $80 each, but he didn't know how to harness the horse. He got more mail every day than I did," Reedy said.

It was not all bad. A few years later, Reedy made the papers when his wife told him to find a cook. He wrote an advertisement that began with a poem from Edward Robert Bulwer-Lytton:

"HELP! We may live without poetry, music and art, / We may live without conscience and live without heart; / We may live without love, we may live without books, / But civilized man can not live without cooks.

"I want a cook who can cook cookably for a fat man and his frau. Just plain cooking for plain folks — on male side of the house. No chef de cuisine I crave — just a cook. Mild and gentle disposition preferred. Out on the farm, close to Nature. Cuckoo of a place for a cook. Pay, anything short of a Wall Street campaign contribution. Victrola in the kitchen; records of all [classic] operas. Picture shows accessible by automobile."

The ad received thousands of responses, and newspaper editors called Reedy up to ask if they could run it in their papers.

Reedy still attracted controversy, though, even in his later years.

For her lecture on free love at the St. Louis Artists' Guild, anarchist Emma Goldman asked Reedy to introduce her. Coming off stage, a commentator told Reedy — a famously rotund womanizer — that Goldman was "probably the only woman in the world whom Billy Reedy could render respectable by his patronage."

Later, during World War I, St. Louis Germans were attacked in the streets, but in typical fashion, Reedy was not afraid to stand up to censorship. He was happy to be labeled pro-German or pro-communist. Reedy was a staunch supporter of free speech. He was convinced that the war was a result of "economic conflict intensifying nationalism into madness," and railed against red-bait committees forming to censor communist artists and intellectuals. Those groups, he argued, could "choke off, eventually, every plea for justice to little nations, or mercy to political prisoners, every protest against the iniquity of coercion and the insolence of office."

"He found himself constantly pleading the cause of literary friends against the efforts of government and patriotic volunteers to suppress their work," Putzel writes. The U.S. attorney general rounded up communists and anarchists to deport to Russia, and after two years in a Missouri prison, Reedy's friend Emma Goldman was on one of the first boats.

In 1916, Reedy collapsed from hypertension. The episode caused a hemorrhage in one of Reedy's eyes, which had to be amputated at Jewish Hospital (later Barnes-Jewish). "Since only one eye was affected, he could still enjoy the vision of pretty nurses, on whom he hoped to exert renewed charm," Putzel writes. "Outside the hospital, he stopped to gaze on a pretty ankle ascending a streetcar step, and on his way out to Clonmel he pondered the beauties of the new short skirts and figured he would be able to get along with just one eye."

Despite the setback, Reedy seemed in fine health. In his appreciation of Reedy from 1918, Bert Love wrote, "Often I have wondered what will become of Reedy's Mirror and of St. Louis in the event of the passing of William Marion Reedy. But he is young — only 55 — and it seems to me that only in recent years has he learned the tremendously happy secret of youthsomeness."

Love was wrong. In July 1920 at age 57, Reedy passed away while traveling in San Francisco. He was in the middle of starting a third-party political movement called the Committee of Forty-Eight, and some thought he was going to run for a Missouri Senate seat.

Love was right, though, that the Mirror could not continue without Reedy. It ceased publication shortly after its founding editor's death.

The Mirror was "The Mid-West Weekly," where articles like "Our Indians as an Oppressed People" ran alongside Robert Frost poetry. It readied the world for T.S. Eliot's modernism, though Eliot might be the last to give it thanks.

And since Reedy, there have been other influential St. Louis literary journals, such as Neurotica, which inspired the Beat poets. Today, St. Louis hosts a half dozen nationally recognized literary journals, including New Letters, Boulevard and River Styx.

When asked about his life, Reedy was never grandiose. "Strictly speaking, ambitions I have had none," he told a newspaper. "I always wanted to write and haven't quite learned how. Anyhow, I've said my say about things and tried to present Truth and Beauty. I keep plugging along for [what's] right as best I can with some doubt that there is any Absolute Right, and much certainty that there is no finality about anything we can fix up in human affairs."

As Max Putzel notes, "Had Reedy shifted his center of activity to New York, as his successful contemporaries usually did, he would have achieved more — though at the cost of that 'autochthonous' quality he prized above success." To be autochthonous is to be "of an inhabitant, of a place" — the je ne sais quoi of a St. Louis brothel or bar.

"I used to wonder why he stayed there," wrote Love. "Now I wonder no longer: I know why. St. Louis needs him. He stays in St. Louis as a benevolent physician stays by a sick patient, to minister, to medicate, to cauterize and cut. Reedy has done more to foster the artistic impulse in St. Louis than any other St. Louisan or St. Louis institution."