Big Star, it's said, was a band ahead of its time. But it's more true to say the band was out of its time, or maybe just out of time, period. Officially formed in 1971, the Memphis-based band featured two creative forces, Chris Bell and Alex Chilton, and the music they made together, and eventually apart, was so melodic, so exhilarating, with a rawness to the wide spectrum of emotions - sometimes fragile, sometimes spiritual, sometimes snarling -- and with harmonies and instrumental passages that echo in the air and sparkle there, its three records, recorded in a scant three years time, remain touchstones and talismans for hundreds of rock & rollers and power-popsters after them.

At the time, of course, few bought the band's records, largely because few could find them. Cursed by record label politics, if not outright malpractice, Big Star never found the audience it deserved. A few latter-day fans were lucky enough to see the band perform at the rare reunion gig, including a legendary show (released as a live recording) in Columbia, Missouri in 1993 that featured original members Alex Chilton and Jody Stephens backed by Jonathan Auer and Ken Stringfellow of the Posies. Critics and musicians championed Big Star, but with the death of Chilton in 2010, the band ran out time it never really had to begin with.

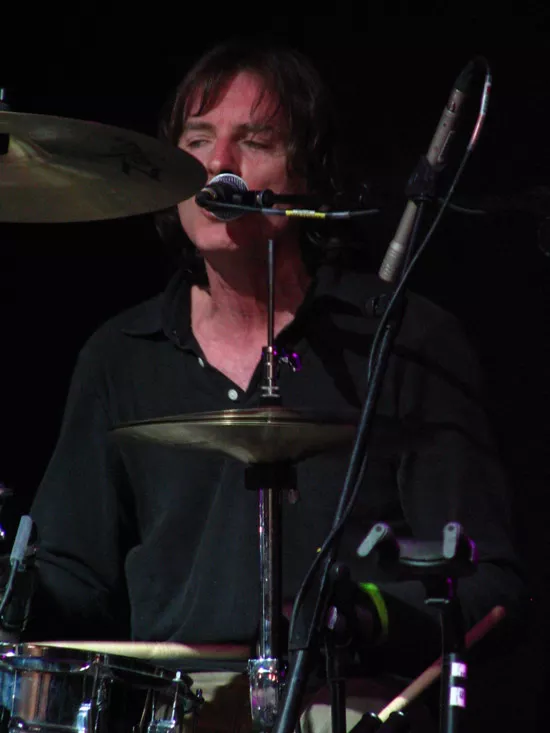

Since Chilton's passing, original drummer Jody Stephens has made it his mission to keep talking about and keep performing the music of Big Star. Stephens' last appearance in St. Louis was with the reconfigured group at a Southern Comfort-sponsored festival in 2006. This Friday, Stephens will take part in an evening in honor of Big Star at the Stage at KDHX (where I'm a DJ and Web Editor). The night will feature a screening of the documentary "Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me," along with a Q&A with Stephens and a performance by members of Magnolia Summer and the Feed, with Stephens joining in on drums.

I reached Stephens by phone at his home in Memphis to talk about the timeless music he made with Big Star.

Roy Kasten: Let's begin with where you work now, Ardent Studios. Before moving to the current Ardent location, Big Star recorded its first album at the original studio on National Street. What was special about that original studio?

Jody Stephens: We tracked at the studio on National and then we moved into our current location over the Thanksgiving weekend in 1971, and completed overdubs and mixed at the new location. The studio on National was my first introduction to a real, live recording studio, so to speak. There is some nostalgia for that studio. When I first walked in the door, Chris Bell and Steve Ray [who left the nascent band before Chilton's arrival] were working on a song called "All I See Is You"; it was for a group they were calling Ice Water. There was something special about National, and then something incredibly exciting about moving to the new studio at 2000 Madison, where it is now. We worked in the off hours, and at the time we were working around people like the Staple Singers, Tony Joe White and I think Led Zeppelin was mixing its third album, unbeknownst to us.

I was watching the Big Star documentary a few days back, and one of the things you talked about is how Big Star, as a band, came to be in the studio. Can you explain what you meant by that?

We were very much a band that evolved in the studio. We all came together there, even the first time in meeting, and from that we did go to Chris Bell's back house and jammed a bit, but outside of that it was the off hours in the studio, experimenting with recording. At that point, Chris Bell could engineer, and Steve Ray and Andy Hummel [the band's original bassist] too. We started to do the odd gig with friends who were having parties; we'd show up and play some songs: James Gang, Led Zeppelin and Beatles covers.

The records are beautifully recorded; they just sound really good.

That was John Fry [producer and engineer who founded Ardent]. He had this amazing touch and incredible ear behind the console. He knew how to make things sparkle. I A-Bed #1 Record with other records at that time, and sonically, John's mixes and recordings really shined with what I compared them to.

And yet none of the records, even the more dense and complex third album, sound like a band tinkering or playing with the studio. You always sound like a band captured live to tape, in the moment.

It could be the early Ice Water stuff sounds like a band tinkering in the studio, but #1 Record and Radio City were pretty well rehearsed, and they were cut as a band. On Radio City, we would go in and we'd track live as a band. The tinkering came with Alex. Jim Dickinson relates the story of getting the song "Kangaroo" from Alex, just vocal and acoustic guitar. And Alex says: "Produce this, Mr. Producer." So on that, Jim added in most all the other instruments. It's interesting, the way that song holds together; it's Alex and acoustic guitar, that was the original recording, and then Jim adds to that recording. It's playing around that nucleus. I don't know how you could follow Alex if they were going down at the same time as all the other things. You would have to really get a feel for Alex's performance before you could follow it. I think the only way to do it is to follow a track that's already there.

You've said before that the Big Star records, and the songs, captured where the members were at that given time. But that's harder than it sounds. You have to show where you are and not tell it.

That's why the records are charmed for me. It didn't tell; everything was related in the lyrical nuances and the musical tracks.

It's well known how Big Star faced serious problems with distribution. You had all kinds of promotion, notices in the press that most bands would kill for. Do you know why the records were never distributed?

I suppose it depends on what point. Al Bell [co-owner of Stax, which had absorbed Ardent] did a deal with Clive Davis at Columbia, and shortly after that Clive left Columbia. Al had lost his champion. Columbia wasn't that interested after that. The secondary and tertiary artists were overlooked; it wasn't in the interest of the label. It's just guesswork on my part. It wasn't unique to us. It happens to artists in general. You have an A&R guy who is your champion, and then he gets let go, and then the band is floundering at the label.

The good thing is that John King, the album promotions guy at Ardent, got it to all the rock writers: Cameron Crowe, Lester Bangs, Bud Scoppa, all the primary writers. Cameron Crowe was sixteen or seventeen at the time. They all said good things about it, and that's kind of why we have an audience now. People into music were reading those publications, and even though it was hard to find, they were seeking it out. You couldn't call it up on Spotify. It might have taken a minute, but when guys like Mike Mills and Peter Buck found it, they would talk about it.