Bill Roberti wants to know what would happen to the city's Public School Retirement Fund if hundreds of eligible teachers decided, all at once, to retire early. So the new interim superintendent of St. Louis Public Schools sends an emissary to confer with pension-board trustees.

The meeting, which Roberti skips, does not go well.

"This is like Napoleon calling up the Queen and saying, 'I need to talk to your chancellor of the exchequer and get all your information,'" grouses trustee John Patrick Mahoney, a former school board member.

In appearance, Roberti may resemble a certain dead French emperor, but the interim superintendent's intentions at the June 30 meeting are far from Napoleonic. Roberti is simply looking to employ a routine corporate cost-cutting maneuver: Reduce the workforce by getting employees to retire early.

It's a maneuver that would seem to make sense given that the schools are awash in red ink, but Mahoney isn't buying. He's seen "sly attempts" to dip into the $900 million pension pot before. He's suspicious of talk about the looming deficit -- one that mysteriously swelled from $55 million in May to $91 million in June. And he's concerned about an atmosphere of crisis, fueled by apocalyptic and often wildly inaccurate information, that's clouded discussion of school reform. "This whirlwind of activity that Mr. Roberti is leading is a trail of uncertainty and fear," Mahoney complains. "We should be sitting down with Mr. Roberti face-to-face and talking about where did you get the $91 million deficit?"

Mahoney isn't the only one with his antennae up. Marlene Davis, pension-board chairwoman and a former school-board president, is openly skeptical. Roberti's talk of closing schools and selling real estate to cover the deficit, she worries, will come back to haunt the city -- especially when suburban school districts opt out of the desegregation plan. "We must look to the future," Davis warns. "We've got 13,000 kids coming back from St. Louis County: The county schools are not going to hold our burdens for us forever."

Memo from Marlene Davis to Bill Roberti: "We can't tear down everything."

Brooks Brothers was never like this. Neither were Plaid Clothing Group, Duck Head Apparel or Tropical Sportswear International -- all clothing companies where William V. Roberti was top dog.

No noisy protesters crowded the board meeting when Roberti pushed Brooks Brothers to expand its line of women's clothing. Nobody ever sued Duck Head, claiming that Roberti was unqualified to run the company.

What has Roberti gotten himself into by becoming interim superintendent? For sailing into uncharted waters, he's getting a lot of grief and a big paycheck.

Roberti is a managing director at Alvarez & Marsal, a New York City-based company that offers, according to its sales pitch, "specialized operational and financial services to underperforming and over-leveraged companies." The twenty-year-old firm never has worked with a public school system, even though the terms "underperforming" and "over-leveraged" fit most urban public school districts.

In May, four newly elected school board members and board member Amy Hilgemann voted to hire Alvarez & Marsal to restructure the district's business and financial systems over the next thirteen months. Their goal: Make the district more efficient, save money and hopefully redirect those savings to boost academic performance somewhere down the road. For its services, Alvarez & Marsal could collect as much as $4.8 million. Roberti is a consultant on the clock, and gets up to $675 an hour.

As part of the deal, Roberti was named the district's "chief restructuring officer," a stealth title for superintendent, succeeding Cleveland Hammonds, who retired on June 30. Roberti's eight-person team includes Rudy Crew, former chancellor of New York City schools. Crew serves as Roberti's go-to guy on academic matters; his "educational advisor." Crew, who won't be in St. Louis that often, will be paid up to $350 per hour.

Aside from Crew, Roberti freely that admits he and his team have no experience or credentials that would qualify them to operate schools. Few, if any, of the ideas that Roberti proposes are new; almost all of them have been tried in piecemeal fashion in other major urban school districts to different degrees and in varying ways. Other districts have privatized departments and outsourced custodial, maintenance or food service. Some districts have closed schools and sold off real estate to save money.

What is different in St. Louis is that a new school-board majority, dominated by members backed by Mayor Francis Slay, moved with great haste in ceding operational control to outside consultants. Within a month of being elected, Slay's slate -- Darnetta Clinkscale, Ron Jackson, Robert Archibald and Vincent Schoemehl -- engineered the hiring of a private firm to virtually take over the district for a year. Hilgemann, elected to the board as a reformer in 2001, joined in the decision; board members Rochell Moore and Bill Haas did not.

The justification given for the precipitous move is that city schools are in crisis and in danger of losing their provisional state accreditation next year. A loss of accreditation would be another blow to the city's efforts to revive its dying neighborhoods, forcing families with school-age children to turn to private schools or suburban districts.

Everybody in St. Louis understands the consequences, but when the mayor's four candidates campaigned on a school-reform platform, they never told voters they'd turn the job over to outside consultants. And they never said they'd exclude key constituencies involved with public education -- such as teacher, district employee and parent groups -- from the decision-making.

No one argues that the district is perfect, but the expense of the contract and the vagueness of its goals have triggered a louder, more immediate outcry than the usual general anxiety about the schools. Opponents have filed a lawsuit, lobbied Jefferson City and staged public protests in an effort to void the contract with Alvarez & Marsal and send Roberti packing. During the board meeting on June 10, audience members chanted "no justice, no peace" and school security personnel were stationed by the podium and in the side aisles. The guerrilla war against the corporate takeover of the district started weeks ago and shows no signs of letting up.

If the critics were just the usual entrenched constituencies, it might not matter. But education experts, familiar with dozens of experiments in public school reform, say what's being tried in St. Louis is a high-risk gamble that could not only prove ineffective, but could do long-lasting damage to the city school system. "I don't think [that] slash-and-burn and then rebuild is the right way to go," says Jeff Henig, professor of education at Teachers College at Columbia University and author of The Color of School Reform, a highly regarded analysis of educational reform efforts.

Amy Stuart Wells, author of Stepping Over the Color Line, a comprehensive look at the St. Louis school desegregation case, agrees. "To have someone come in, tear it apart, and then bring in a leader [a permanent superintendent] is just stupid," Wells says. "Whoever is going to lead this system into the future needs to be part of these decisions about what gets cut, what doesn't and why. Even the private sector should know that."

None of the criticism fazes Roberti, a self-described "problem solver." He's used to walking into places where some of the people hate seeing him and others hold out hope. And he has no illusions about the complexity of the job: "We know we have a tough assignment on our hands."

But it's an assignment with limited responsibility: Roberti and his band of hired guns will be gone by next June -- if not earlier. And they won't have to live with the consequences of their actions.

That such a drastic and unprecedented approach to reform is underway is a testament to the school district's troubled history. At its peak in 1967, the school district served 115,543 students. Today, enrollment is just 42,036 -- an astounding 64 percent drop. The decrease can't be blamed entirely on the exodus of city residents to the suburbs -- the city's population dropped by less than one-half during the same period. Race played a major role and continues to do so.

Indeed, the school board makeover that brought Alvarez & Marsal to St. Louis has its roots in the landmark desegregation suit filed in 1972, when Minnie Liddell went to federal court claiming her son was receiving an inadequate education because he was African-American. That led to the nation's most expensive school desegregation plan, a large component of which was a court-sanctioned, state-subsidized voluntary transfer program started in 1983 that allowed black city students to attend St. Louis County schools.

Missouri attorneys general, from John Ashcroft through Jay Nixon, sued to end the desegregation plans in Kansas City and St. Louis, trying to get the state out from under millions in payments each year. It wasn't until 1999, through a combination of a city-passed sales tax, state legislation and the agreement of the plaintiffs, that the desegregation suit was settled.

As part of the deal, more than 10,000 African-American city students continue to attend school in the county, though that could end in the next few years if the suburban districts drop out of the program. During the negotiations that led to Senate Bill 781 that settled the suit, critics of city schools who demanded reform pushed for language that cut the size of the 12-member board by five. The legislation put four of the remaining seven seats on the April 2003 ballot.

As that election approached, an education coalition was formed to pick a slate of candidates for the four open seats. Slay swung into action. The mayor, his chief of staff Jeff Rainford, and his educational liaisons Robbyn Wahby and Reverend Earl Nance helped screen prospective candidates. They settled on Schoemehl, a former city mayor and current president of Grand Center Inc.; Clinkscale, patient-care director at Barnes Jewish Hospital; Jackson of the Black Leadership Roundtable; and Archibald, director of the Missouri Historical Society.

Slay loaned $50,000 from his campaign fund to support the slate. Major area corporations kicked in with Anheuser-Busch, Ameren and Emerson Electric each giving $20,000. Energizer Eveready Battery Company gave $15,000. The coalition raised more than $235,000.

Though the slate, which handily beat fourteen other candidates, was midwifed by City Hall, Slay's top aide insists the school board isn't taking direction from the mayor. "Anybody who says otherwise is full of baloney," Rainford says. At the same time, Rainford applauds the board's decision to hire Alvarez & Marsal. "When one person comes in without any kind of support, change just doesn't happen. One person against the system is a mismatch. So the board made the decision that rather than bringing one person in, we're going to bring a team in because it would take forever for one person to do it and we don't have forever."

What the school board wants to do is turn around a district that has deep-seated difficulties. Its students are poor, its test scores are below average and its image in the general community is even worse than its reality.

The skimming off of the middle class has been going on for decades. African-American parents worried about the quality of city public schools or concerned about safety can opt to send their children to county schools. Estimates during the '90s were that 60 percent of the city's school-age white children attended private parochial schools.

More than 80 percent of the students in the city public schools qualify for the free or reduced lunch program offered by the federal government. The state average is 38 percent.

The district's Missouri Assessment Program (MAP) test scores have improved in the elementary and middle school areas in the past four years, but are still below state averages. In high schools, MAP scores have gotten worse during the same span, with only 1.2 percent of juniors and seniors scoring in the advanced or proficient levels for science.

The drop-out rate has fallen to 7.8 percent, down from 26 percent when Hammonds became superintendent in 1996. During the same span, the graduation rate rose to 53.3 percent from 38.6 percent, but that still is well below the statewide rate of 80 percent. The attendance rate for the district of 89.5 percent is less than the state average of 93.8 percent.

Critics often talk about the district's top-heavy administration, but that's a charge that's hard to quantify. According to statistics kept by the state, the district ratio of 219 students for each administrator is comparable to the statewide ratio of 209 students for each administrator.

The mobility rate for students, which is the number of students who transfer in or out divided by attendance, was 133 percent in the city in 2002. In Clayton it was 14 percent; in Rockwoods it was 9 percent.

Other cities faced with similar dreary public school scenarios have seen their mayors take over the schools with state legislative support. Due to the settlement of the desegregation case, Slay instead had the option of letting a new school board do the work. Tapping Schoemehl was a mini-coup: the former mayor increased the notoriety of the slate and put somebody in the mix accustomed to public controversy. And Schoemehl has a record of turning to the private sector for answers to vexing public-service problems: It was during his tenure that St. Louis got out of the business of operating public hospitals and instead contracted with a private-management firm to operate Regional Medical Center. The move cut hundreds of jobs from the city payroll. Ultimately, Regional closed in 1997.

After Schoemehl's unsuccessful bid for governor in 1992, he returned to the business world before taking the top job at Grand Center. Last year, Schoemehl began thinking about running for the unpaid post on the school board. He crammed for the job by reading Henig's book as well as City Schools and City Politics co-authored by Lana Stein, the chair of political science at University of Missouri-St. Louis, and Building Civic Capacity edited by Clarence Stone.

A veteran of city politics, Schoemehl is not surprised by the vocal protests during board meetings and the unrelenting criticism of the new board from some circles.

"There's going to be plenty of grief about this," Schoemehl says. "What has ever changed that hasn't caused grief? I would be disappointed if in a year from now we didn't look back on this and say, 'We made a good decision. We've increased the capacity of this school system to provide educational services to children.' It's not just about savings, it's about redeployment and adding quality."

The ex-mayor insists that a for-profit, private firm has to be worth the $4.8 million it will be paid to restructure a district that's so deeply in the red. After all, Alvarez & Marsal is in the business of saving its clients money.

"In the private sector, they wouldn't exist if they didn't. That's my point. These people make a lot of money," Schoemehl says. "The private sector is unforgiving in these sorts of situations."

The private sector may be unforgiving, but at least it's private, a realm where Roberti is comfortable. Dealing with the media has been a big adjustment for him since becoming the district's interim superintendent.

"If there was one big surprise to this whole situation, it's how much time we spend doing this," Roberti says during an interview. "Quite honestly, that takes away from it." It's not that Roberti isn't gabby or glib on his feet -- he is. It's just that in other venues it's not a priority, or even necessary.

The firm's co-founder Bryan Marsal is running troubled HealthSouth Corporation and is often quoted in the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times, but that's the exception.

"We're not used to dealing with all this press," Roberti says. "When we go in to fix a company, we're not used to this whole PR thing. Normally we go in, we do our work and yes, people are interested.... but it's not constant."

"When you're in the public eye like this, it's constant," Roberti says. "It's constant."

Roberti carries himself like a man used to being in charge, walking briskly, dressing well but conservatively. The 56-year-old has a master's degree in business administration from Southern Methodist University and an undergraduate degree from Sacred Heart University, where he is on the board of trustees and is a "professor of retailing." He's Catholic to the max, having recently returned from a vacation in Rome where he toured churches.

Roberti hasn't talked about his politics, but he has a history of making donations to conservative Republican candidates. In 1995, he gave $1,000 to Lamar Alexander, a former U.S. Secretary of Education and Tennessee governor, who was trying at the time to win the Republican nomination for president. That same year Roberti gave $6,000 to Steve Forbes, son of the business-magazine magnate who was running for president. One Democrat Roberti did assist was the late U.S. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan (D-New York), who received $1,000 in 1994.

Though he has spent recent weekends in St. Louis, the contract with the district allows Alvarez & Marsal $110,000 for travel expenses. That money can be used by Roberti for trips back to his Connecticut home on weekends.

Roberti may feel as though he's in the media's spotlight, but for the most part, the media have embraced the newcomer. The St. Louis American, a local weekly with the highest circulation in the African-American community, has embraced the school board's actions -- no surprise, given that the newspaper's publisher Donald Suggs was campaign treasurer for the winning candidates and also served on the committee that recommended Alvarez & Marsal.

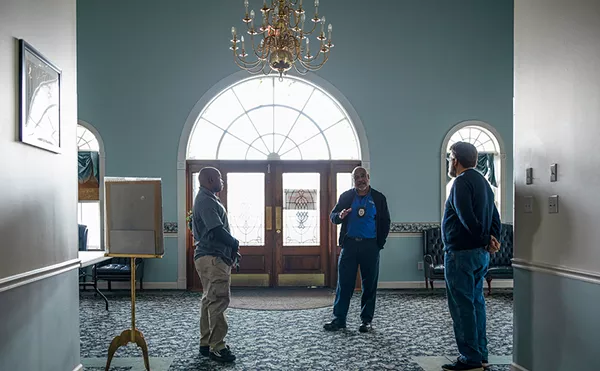

The Post-Dispatch editorial page has been behind the board's decision from the beginning, and its news pages haven't been unfriendly to the new management team, tending to downplay or even ignore public opposition. For example, the Post barely mentioned the raucous school board meeting on June 10 that was packed with 500 people and at times seemed to edge out of control. Nor did the Post report on an education coalition meeting on June 21 at Harris-Stowe State College that featured, among other highlights, a shouting match between Suggs and school-board member Rochell Moore. That Saturday morning meeting apparently was scheduled too early for local television news crews, too. The paper also failed to cover the pension-fund meeting on June 30.

From Roberti's perspective, there isn't much new or different in what he's doing. Revamping a school district shouldn't be all that different from restructuring a company:

"It is ordinary business as far as I'm concerned," Roberti says. "We've got logistic problems, we've got distribution problems, we've got organizational problems, we've got systemic problems, we've got finance problems. Those are the things that I know how to do well and I've been doing them well for a very long time. Whether I was a CEO of a clothing company or a manufacturing company, or whatever, I've always been a problem solver."

Rudy Crew, his sidekick in the endeavor, previously headed school districts in Tacoma, Washington; Sacramento, California; and New York City. Crew now lives in the Bay Area of California where he works for the Stupski Foundation of San Francisco. He won't be in St. Louis that often, but Roberti emphasizes that Crew will be consulted on how decisions affect education.

Crew doesn't see what Alvarez & Marsal is attempting to do as that hard to grasp. "Everything we need to do to improve this system is in the realm of the known," Crew says. "There is nothing unknown about this. We know there have to be some improved business practices, we know there have to be some improved instructional practices, but we know what it takes to be able to do this. It's just a question of actually creating the organization that takes advantage of what we know. I don't think this is a question of having to change the entire governance structure, but I do think you have to change the organizational structure."

And Crew, having left New York City after fighting Mayor Rudy Giuliani over the mayor's support of vouchers, knows the tricky part often is after the dust settles.

"Where urban public schools usually lose, is that the reform that they went through is so politically costly, it's hard to sustain the leadership to keep it going," Crew says. "If you look at public school systems en masse, what you find is sustaining the change over a long period of time becomes incredibly hard to do."

Crew's presence is critical for Roberti because as an African-American former head of the nation's largest urban school district, Crew provides educational credibility even though he's a long-distance phone call or airplane ride away.

Even when Roberti and Tony Alvarez made their initial pitch on May 21 to a school board selection committee, they admitted repeatedly that they knew little about education. "What experience do we have with teachers and principals? Zero," Alvarez told the committee. "What experience do we have in private industry? A lot."

Neither Alvarez nor Roberti tried to hide that revamping the district would mean people losing their jobs. That's how money is saved. Squeezing money out of the budget would mean fewer people working for the district.

During his pitch Alvarez said it had been his experience that "most companies have 10 to 20 percent of people not performing good work," but admitted they would have a "difficult time coming up with yardsticks. When we come in, we don't have that data." Roberti told the committee there would be "head count reductions" as they would "knock out redundant activities."

One non-school board member of the selection committee, J. Patrick Mulcahy of Energizer Holdings Inc., worried about how these actions would be greeted by the public. "You have a community issue," said Mulcahy. "How do you sell this? How do you make it sing?"

One argument was that the study eventually would pay for itself. Alvarez said he would be "stunned" if the savings from the restructuring didn't exceed 10 percent of the district's $450 million budget. And if the situation got ugly, Alvarez recommended doing what private industry does: hire a "crisis PR firm" to handle the uproar.

Once the downsizing, privatization and new systems were in place, Alvarez & Marsal would split.

"When you get the new superintendent, we can get out of the way," said Roberti. "We're happy to leave Dodge. We're gone."

That sort of rip-and-run, fix it and exit technique worries Jeff Henig, the Columbia University professor.

"When you just rip things up before you understand why they are the way they are, you're often ripping healthy plans along with the bad ones," Henig says. "Sometimes things are the way they are for reasons of inertia and political privilege and protection of patronage and all kinds of bad reasons. But other times things are the way they are because communities by experiment, history and evolution find solutions that work."

Changing a school district involves getting the people who do its work to buy into the concept.

"You need to begin doing it in a way that enlists support of key groups within the community rather than imagine that it can be done by these folks who just got into town," Henig says. "It's not clear that the wounds and the messiness go away when they leave town. The supposition is you go through this tough period and then you're over the hump. I'm not certain it's as clean as that, that the wounds don't remain, that the resentments don't remain and continue to fester."

If the recent school board meetings and public meetings are any indication, the "tough period" is in full swing. At first opponents might have been dismissed as fringe dwellers and the usual malcontents, but as the spin from Roberti, the school board and the mayor's office escalates about how grim the district's finances are and how drastic the remedy must be, the opposition ranks grow.

Clearly Roberti did not know what he was facing. For example, he claims he wasn't aware until June 22 that Rochell Moore had recently been treated for mental illness and had tested positive for cocaine. Moore faxed her medical records to the Post-Dispatch thinking that if the newspaper had those documents, her allegations that she had been set up would be made public. Predictably, the May 6 article on her involuntary commitment at Barnes-Jewish Hospital did not improve her status on the board.

On May 31, the day Alvarez & Marsal was hired, Moore stood outside district headquarters handing out a news release stating her opposition. She also told reporters she would never go to lunch with Amy Hilgemann again and that she "would watch where she put her coffee." Moore has had a falling out with Hilgemann, her former confidante and ally, and has alleged that someone put something that made her ill, possibly cocaine, in her coffee.

Though his rhetoric pales by comparison to Moore's, the board's other dissident, Bill Haas, has referred to the board majority as "Nazis" and calls their actions "dysfunctional, unlawful, self-righteous, sanctimonious, hypocritical and self-serving." He's less vitriolic when it comes to Roberti and his staff, saying "they may end up being worth every dollar we're going to overpay them."

For most of those opposed to the hiring of Alvarez & Marsal, the money is the issue: The firm cost too much and its compensation is not linked to any academic improvement. From the start, Lizz Brown's morning talk show on WGNU (920 AM), recently expanded to four hours, has provided a constant drumbeat against the board's action. Brown's been more than a vocal partisan in the debate: She recently filed a lawsuit with six other plaintiffs seeking to block Roberti's appointment and void the Alvarez & Marsal contract. A hearing in circuit court is scheduled for July 21.

"What is so twisted and wicked about the argument is no one can argue that the city schools are so bad it doesn't matter what we do," Brown says. "But yet and still that's the argument that is being made here, that it doesn't matter what we do, just do something. That's bull."

Brown reserves special criticism for the Black Leadership Roundtable, the African-American organization that threw its support behind the school-board takeover. Key roundtable members include Jackson, now the school-board vice president, and publisher Suggs. Brown contends the group's out of touch with the African-American community. "No one in that group was elected, no one was chosen by the community," Brown says. "These are largely black businesspeople who are getting a hustle from the deals that they cut as being the gateway to black people."

Jackson's response is direct: "That's bullshit."

"Does Lizz Brown represent the black community?" Jackson asks. "Who represents the white community? Who determines the real representative of any group of people? Who's the legitimate leader of the black community? If the people on the Black Leadership Roundtable are the heads of the major black organizations in the community, they represent those people. Some might say they're leaders."

One key leader has left the scene. A weary Cleveland Hammonds stepped down from the district's superintendent's job a year before his contract was up, sensing the shifting winds of change. Under his six-year tenure, some MAP scores improved and there were improvements in drop-out and graduation rates, but the public perception of the system remained negative. He was brought in as a "reform" superintendent and he thinks he did his share of that.

"The problem with reform is the definition. The problem with reform is the timetable. For the Post-Dispatch, reform meant if I didn't have about five public hangings a week, then I'm not reforming," Hammonds says. "You can't find any place in this country where reform has happened in two or three years, but that's still the expectancy. There might be significant changes in reading scores, but because we're still not where we should be, because we're still not Ladue or Clayton, people feel like we're failures."

Of Missouri's 523 school districts, 22 are provisionally accredited and only Wellston's is unaccredited. Hammonds leaves a provisionally accredited district that meets five of the necessary six out of 12 requirements for accreditation. At a point earlier in his tenure, the district met only three of the 12 requirements, but was saved from losing its accreditation when the desegregation lawsuit was settled.

Hammonds' main defense is that since no one can point to a large city public school district that is hitting on all cylinders, the fault might be in societal priorities, not in individual cities.

"As a people we have not been willing to commit ourselves to the kind of time and focus that it's going to take to bring urban systems up to our expectations. We don't want to put the extra resources in so we complain about the incompetence. There's no way in the world that every major city in the country is full of incompetent people. The cities are full of kids with a lot of needs, with kids who need additional help. People don't want to deal with that."

For the next year, Roberti will be in charge and he'll be running his education questions past Rudy Crew, who is often mentioned on the short list of candidates when an opening occurs for a superintendent in a large city.

Deborah Meier, the 75-year-old past winner of a MacArthur "genius" award, was not impressed by Crew during his tenure in New York City. Meier was founder of Central Park East elementary and secondary schools in Harlem and is seen as a pioneer and innovator in urban education. She is co-principal of Mission Hill Elementary and Middle School, a predominately African-American school in a poor section of Boston.

"Crew is a better talker than anything," Meier says. "He didn't succeed in any of the places he was at. He claims to have succeeded in Tacoma, but as soon as he left, the scores went back down. In New York, I don't know of any evidence that anyone claims that he was successful."

Meier doesn't see the value in relying on high-priced consultants or the private sector to fix the real or perceived problems of a city school district. "It's intriguing, always, this rotation of people who go from one superintendency to another," Meier says. "If they had some idea about what it is that would be necessary to change school systems, why haven't they done it? I'm not even blaming them for not knowing how to do it, I'm just blaming people for thinking that is who you need to rely on for expertise."

The mayor-taking-charge approach is gaining popularity. Chicago's Mayor Richard Daley lobbied the Illinois legislature and got control of his city's schools. Daley hired Paul Vallas to run the district and he received credit for improving the financial side of the system, but Chicago's schools are at best comparable to those in St. Louis, certainly no better. Vallas moved on to Philadelphia, where Edison Schools, a New York for-profit company, runs twenty public schools.

Those decisions had been made under a Republican governor and since former Philadelphia Mayor Ed Rendell, a Demo- crat, became governor in January, there has been a de-emphasis on private management of the city's public schools. A contract for Chancellor Beacon Academies to run five schools in Philadelphia was canceled in April when Vallas thought the company had little impact on the low-performing schools.

In New York City, four years after Crew left, Mayor Michael Bloomberg has achieved the control that former Mayor Rudy Giuliani desired. Bloomberg has brought in former federal prosecutor Joel Klein to run the $12 billion, 1.1 million student school system.

Bloomberg is cutting $175 million out of the school budget, but also recruiting business executives and educators from universities to work for less than they would normally make. Some high-profile executives are donating their services pro bono, and a training facility for principals has been set up with $75 million in private funds.

Taking over the schools doesn't seem like something Slay wants to do -- for now. His strategy is deft but political, allowing him to look supportive of change yet still remain an arm's length away if the situation implodes. When Slay issues a statement saying the school administrators spent money "like drunken sailors," that's a popular statement with his political base who either never sent their children to public schools or abandoned those schools long ago. That Slay presides over a city budget that's more than $50 million in the red is beside that point.

Rainford says Slay's decision not to seek direct control of the schools was an "operational" decision, not a political one. "We've got our hands full taming our own bureaucracy. We're still focused there. We have to improve the delivery of city services and bring investment back into the city. That is a full time gig," Rainford says. But he admits taking the schools over remains an option. "This is the last, best chance in the current structure to improve the schools. The mayor has never ruled it out in the future. It's certainly something his constituents have asked him to do or have pushed him to do. At this point, he still thinks the current process holds out some hope."

But Slay's staff doesn't know the city schools like Amy Stuart Wells, the author and professor -- and Wells says she has no reason to be hopeful about Alvarez & Marsal's involvement.

"I don't know how you can ever downsize, ever trim the fat when you don't know enough about the enterprise to even know what the fat is and what is critical. It's so absurd. People think they can come in and solve these problems of urban public schools without even defining the problem," Wells says.

"Fixing the budget for one year is not going to solve the layers and layers and years and years of inequality and neglect. It's a social problem; it's not a budgetary problem."

During a break in a particularly contentious meeting of the education coalition on June 21, Bill Roberti is standing in the hallway outside a third-floor lecture hall at Harris-Stowe. Roberti may be having second or third thoughts about his new gig, but it doesn't show on this Saturday morning. Holding a Styrofoam cup of coffee in hand, Roberti is wearing a navy blue blazer with olive khaki pants, tan socks, brown tassel loafers and a pink-and-white check button down shirt with no tie. Crisp, calm and casual.

Roberti is engaged in a give-and-take with several school employees, including custodian Gregory Bonnett, who is sporting a gray T-shirt, khaki shorts and sandals. The exchange is direct, but polite. Jobs are the issue. Bonnett tells Roberti he's concerned that low-income employees will lose their jobs when services are contracted out to private firms but that highly paid administrators will be untouched. "When you leave, those same people are still going to be at the top," Bonnett says. "That's where the problem is."

Roberti promises everything is under review and nobody's safe.

"I am going to restructure this entire system," Roberti says. "I'm going to make cuts everywhere, certainly at the top. We as a team evaluate all that, what's nice and what's necessary. What do we really need? What don't we need? Who's really got a job and who doesn't? How does this work? Tear that whole thing down and then restructure it into an organizational structure that works. How many people have just one direct report? What's the span of control? Who's the lead? Who's executing? That's what I have to figure out. This is not an easy task."

Roberti tries to leave Bonnett and the other employees with the thought that his firm might not end up being as expensive as advertised.

"If I get my job done here by December and I'm finished and the school board is lucky enough to find some wonderful, well-qualified superintendent to step in here, I go home and the money that was planned for that last phase doesn't get spent," Roberti adds. "I don't just walk out with a giant check."

For the district that writes that check, the concern is more about what Roberti will leave behind.

Correction published 7/16/2003:

The original version of this story incorrectly indicated that a 10 percent savings on the school district's $450 budget would nearly cover Alvarez & Marsal's projected $4.8 million consulting fee. The above version of the text reflects our renewed commitment to arithmetical rigor.