Part myth and part reality, combining an imperfect blend of history and the present, it is a strong streak of Dixie that St. Louis tries to deny, preferring to think of itself as progressive and far above all the raw racial passions of the Deep South.

In truth, though, St. Louis shares some of the South's maddening contradictions and more than a trace of the region's racial sins.

Slaves were once sold on the steps of the Old Court House. And Jim Crow once reigned supreme here, even though black aldermen represented wards through the early decades of the last century, elected for political service in a town where they couldn't eat, shop or be hospitalized with white people.

Today St. Louis is blessed with racially mixed neighborhoods that truly deserve the clichéd tagline of diversity. But the city is still afflicted with a fragmented political system, often fueled by casually raw racial appeals by both black and white politicians that smack of the color-bound politics of the Old South.

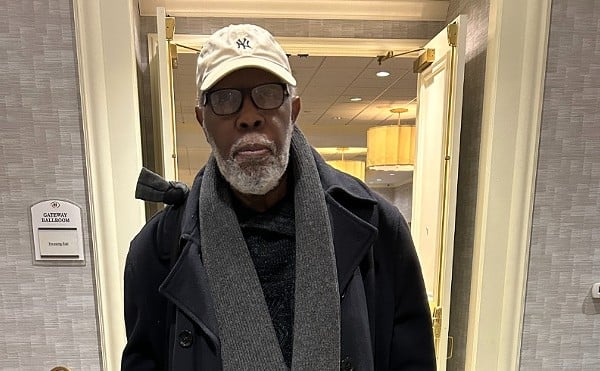

"We have the worst of both the South and the North," says former deputy mayor Mike Jones. "We have the alienation and lack of community of the North without its energy and productiveness. We have the conservatism and slowness of the South without the sense of community. If you think about New York and a large Southern city and take the worst aspects of both of them -- that's the cultural fulcrum of St. Louis."

Nowhere is this more true than in the intertwined issues of race and politics. St. Louis' ongoing racial dilemma is a subtler and more nuanced problem than the Old South edition, lacking the searing fire that branded the national consciousness with the violence of Mississippi or Alabama. But a palpable animosity between blacks and whites -- between North Side and South Side -- is still an everyday fact of life in St. Louis, particularly in politics.

"When it comes to race, St. Louis is like a dry drunk," says Jones. "It might never take another drink, but it has never kicked that addiction."

This homegrown animus -- soft-spoken, rarely shouted -- was on full display in the days leading up to last Tuesday's primary election, with candidates white and black throwing down the race card in an unvarnished fashion that is customary to politics here.

In a retail sort of way, St. Louis pols often play a more blatant racial game than the codified appeal George Corley Wallace of Alabama used in one of his early-'70s gubernatorial campaigns, during which he continually railed against "the bloc vote." Their actions rank right up there with former U.S. Senator Jesse Helms' infamous campaign ads that stirred up white anger about affirmative action during the North Carolina senator's 1990 race against Harvey Gantt, Charlotte's first black mayor.

On one side of the city's racial divide, Collector of Revenue Ronald Leggett, a South Sider who was once a valued member of Slay's posse, bought himself some backyard insurance by running an ad in the South Side Journal that featured a picture of himself and his black challenger, Howard Hayes, who lost to the long-time incumbent.

The ad didn't even deign to list Hayes' name. Beneath Hayes' photo stood the simple word "Opponent." In the copy, there was an accusation that Hayes' campaign headquarters was located in a building that owed back taxes. Not much else was said in this ad. Not a lot needed to be said -- the pictures underscored the racial context.

More was said in one of the most striking examples of St. Louis' version of racial card flipping -- the full-page ad unsuccessful 4th District state Senate challenger O.L. Shelton ran in the August 1 edition of the St. Louis American, the city's premier African-American weekly.

Featuring pictures of prominent black civic leaders from the past and present, such as former city assessor Gwen Giles, former comptroller and 4th District state Senator John Bass and U.S. Representative William "Lacy" Clay, son of the city's most prominent black politician, Shelton's ad also sported a picture of his opponent, incumbent state Senator Pat Dougherty, with a big white 'X' superimposed over his smiling face.

"These leaders shed their blood, sweat and tears over the last 40 years to win ... hold ... and represent our interests in the 4th State Senatorial District," reads the copy in Shelton's ad, clearly referring to everybody but Dougherty. "Let's take our district back."

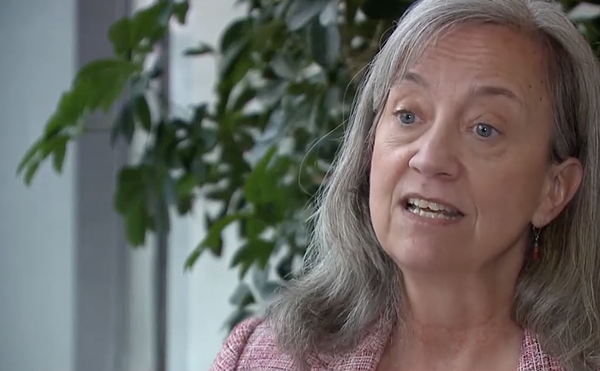

As the American's Political Eye column of the same edition notes, Circuit Attorney Jennifer Joyce, attempting to show some independence from her South Side base and carve some North Side inroads by walking the streets of crime-plagued neighborhoods and making frequent appearances before civic organizations to talk about crime [Jim Nesbitt, "North Side Pitch," July 31], cut a radio spot for Shelton.

But the South Side Shark's picture doesn't appear in Shelton's ad on the preceding page. There you have it, though -- the Southern-style contradiction within St. Louis' version of racial politics, Shelton's purely racial appeal in print counterpointed by the support of the Shark with her solid-gold South Side pedigree.

The Shark even serves up a fat rationalization for Shelton's use of the race card.

"It's a politically compelling point for him to make that that district has historically been represented by black elected officials," she says. "His actions, from my point of view, have not just been color-blind but courageously so."

There's another way to look at this: Shelton backed Joyce's run for circuit attorney over two black challengers, and the Shark is making a down payment on that political debt. But the Shark doesn't like her support of Shelton portrayed strictly as quid pro quo, particularly in light of the racial appeal made by her newfound political buddy.

"That's not the reason I'm supporting him," she says. "Part of what I like about O.L. is that he's proven to me that he's not going to make a decision based on race but on what's right for his constituents.... He went way out on a limb and supported me, and that told me a lot about his character. That was a real profile-in-courage move that spoke volumes to me."

"Profile in racial politics" would be a more accurate description of Shelton's ad, says Ann Auer, Dougherty's campaign manager: "Basically it was a racial ad that ignored the population in the southern part of the district. Since redistricting, it's a much more diverse district, and [Shelton] chose to ignore that."

Successful challenger Yaphett El-Amin's much smaller American ad against incumbent state Representative Ocie B. Johnson (D-57th District) made another pointed racial appeal. It featured a faceless silhouette of Johnson "and his boss," Mayor Francis Slay, who isn't named but whose smiling portrait appears opposite El-Amin's.

The ad portrays Johnson as a Slay puppet, playing to the distaste black voters hold for Frankie the Saint, the quintessential South Sider, for his ramrodding of a redistricting plan that took Alderwoman Sharon Tyus' 20th Ward away from her.

El-Amin's ad also touches on another old sore point for the city's black voters and pols -- the uneven distribution of $37 million in federal and local street-improvement money two years ago, $35 million of that amount going to projects on the South Side and the central corridor, but just $2 million to the North Side.

Although some weighty technical reasons help explain this imbalance, those arguments got lost in the heated political debate of a city where everything is viewed through the fractured prism of race. And even though this battle took place on former Mayor Clarence Harmon's watch, Frankie the Saint got tagged for pushing a South Side-slanted deal because, as president of the Board of Aldermen, he rammed the project list past the board after it failed a first vote.

All of this emphasizes the Southern streak in St. Louis, a clannish city that doesn't feel Dixie-fried but seems to share some of the same ghostly contradictions and seems rooted in a cynical form of racial politics that few want to acknowledge and nobody wants to challenge.

"Most of us do not acknowledge that we're Southern," says former Mayor Freeman Bosley Jr. "It's denial. We'd rather be perceived as more Northern or Midwestern, but it's clear that we still have a lot of Southern influences. It's Southern in the sense of racial polarization. There's a very strong reluctance to acknowledge the race issue here."

Economic stagnation and the city's steady population loss perpetuate this political status quo and the standoff between blacks and whites, says Jones. Unlike the booming cities of the Sun Belt South, there isn't a steady stream of newcomers hitting town, challenging the old political and economic orders and pushing their way upward through the city's corporate and civic ranks.

Down in Alabama, there's a psychobilly group known as the Drive-By Truckers, fronted by lead singer Patterson Hood. On a Friday night at Frederick's Music Lounge, several weeks before the primary, they took the tiny stage to sing a fiery sermon of Southern perfidy and redemption.

Southern icons both tainted and sainted pepper the music -- Wallace, Bear Bryant and Birmingham, the city of church bombings and four dead black Sunday-school girls, the turf of Bull Connor, firehoses and snarling German shepherds.

When the Speedloader lived in Birmingham, the city was on the cusp of electing its first black mayor and Wallace was gearing up for a final gubernatorial run that would see him garner 90 percent of the state's black vote -- testimony to the South's political and racial contradictions.

Bryant still rumbled on the Alabama sidelines, a living legend in his hound's-tooth hat, cutting Mother's Day commercials for Southern Bell with a voice full of filterless smoke and Old Testament age: "Have you called your mama lately? Sure wish I could call mine." He won his first Crimson Tide national championship in 1961 with a lily-white team; he won his last in 1979 with a fully integrated squad.

Thanks to Wallace, though, it's much easier to ignore such progress, Hood sang in a raspy voice. Easier, too, to put a Southern accent on racism and all its permutations, even though it's still a nationwide problem that ignores the comfortable and one-way cliché of rednecks and Kluxers throwing down on blacks.

Wallace is in hell for his racial sins, Hood sang. And the devil is a Southerner, throwing another log on the fire for the governor, serving him some good sweet tea and sporting a Wallace sticker on his Cadillac.

But these days the devil just might feel equally at home in St. Louis -- particularly when it comes to the issues of race, politics and the city's own "Southern thing."