The first time Don Marsan paddled out to explore the mine, he told his wife, Teddy, that he'd be back in four hours. He was gone for nine.

At the time, Marsan was already an experienced caver with thousands of hours logged traversing natural caves, guiding newbie spelunkers and training search and rescue teams. But he'd never before kayaked an underground lake, let alone a mine.

Still, he simply paddled his way into the darkness one morning in September 2012. His supplies consisted of a life jacket and flashlight. No food, no water. Marsan keeps a copy of the map he drew two months after that first expedition and uses it to trace his meandering first journey.

"When I first started checking this place out, Tom said, 'Just stay to the walls, and you won't have a problem.'"

Marsan emits a bemused cackle.

"Well, that's not true, and I found, after about two hours on the water, that everything looked the same."

Even more confounding, there are parts of the mine that are utterly different. The support pillars that miners carved out of stone decades ago, and by which Marsan eventually learned to mark distances, can vary greatly in size. Some are little more than 20 feet in diameter, while others are more than 50 feet. Certain areas of the mine have pillars carved out in laser-precise fashion in a ten-by-ten grid. Older sections feature asymmetrical beams with irregular outcroppings that seem to exist for no other reason than to block otherwise orderly aisles.

After nine hours out on the lake that first day, Marsan finally managed to find his bearings by counting pillars and spotting a few conspicuously soot-stained walls. He paddled blind through the squeeze tube, not knowing what lay on the other side.

"This is his M.O.," his wife says. "He takes adventures to the nth degree. I didn't get really concerned about him until he was gone for eight hours."

Marsan and Teddy both come from military backgrounds. He joined the army in 1967, and she and Marsan met and fell in love in the early '80s while both were stationed at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. When he left the military in 1989, the couple moved to Teddy's home state of Missouri.

"In the military, you had camaraderie, you knew to depend on each other," Marsan says, attempting to trace the strange path that brought him to the caving-and-kayaking business. "In civilian life you only depend on yourself, because nobody is out there to help you. That's what we learned from the get-go."

By 1995 the stress of civilian life had reached a tipping point. Marsan bounced between warehouse jobs, driving freight and doing occasional mechanic work around Jefferson County. At the same time, the couple says, their marriage began falling apart.

"We were getting ready to divorce after fifteen years," he says. "We just didn't have anything in common."

Thankfully, a work friend of Marsan's suggested they attend a meeting of a regional caving group, Meramec Valley Grotto, that holds monthly meetings at the Alpine Shop in Kirkwood. Marsan took an immediate liking to the exploration and sense of community that reminded him of his military days.

Teddy, on the other hand, had to overcome a clawing fear of tight spaces and water. She pushed herself to keep up with her husband.

"I'm very claustrophobic," she says of her first cave trips. "They'd take me to the entrance of the cave, I'd get in three feet, come out, vomit and then have to pick up a shovel and bury it."

As for Marsan, he never had a problem with strange environments. Indeed, listening to his life stories is like hearing a tall tale come to life: A sixth-grade dropout, he spent summers hopping trains between Boston and New Hampshire before joining the army at eighteen and shipping off for multiple tours in post-war Korea. After leaving the military he volunteered as a firefighter. Now, in his golden years, he leads tour expeditions into a watery cave.

"Every time I go in, there's always something new in here," he says. Marsan regularly searches for the exact spot where the groundwater poured in decades ago to create the lake and scours for new passages and left-behind machinery.

"There are a few places I can't find again, a few pumps," Marsan says, mentioning how he spotted a trunklike pipe, maybe a foot (or more) in diameter and ten feet long. He doesn't know what it was used for, but that's not really the point.

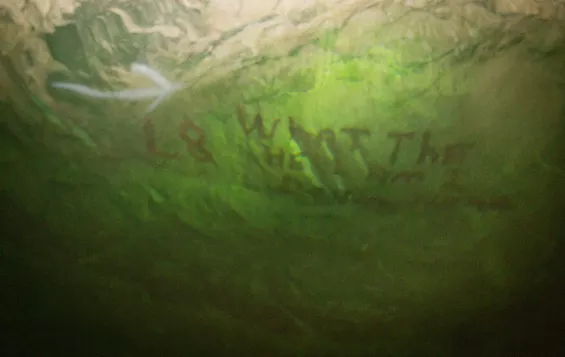

Later, back out on the water, Marsan's kayak casts a twelve-foot halo as it glides toward a wall. He halts the boat with a prod from his paddle and points his lantern into the crystal-green water.

"Look down on the wall," he says.

It takes a minute for the water to calm and the ripples to flatten. Below the water's surface someone long ago wrote in red paint, "What the hell am I doing here?"

Marsan grins, his expression lit by the ethereal interplay between water and light, stillness and shadow, present and past.

"Ain't this place awesome?" he says again.