As the novel coronavirus and its associated disease COVID-19 burst onto the global stage, its seemingly indiscriminate rate of infection caused some to label it the "great equalizer." While the virus has the potential to infect anyone, alarming new demographic data demonstrates that while the virus itself may spread indiscriminately, it exacerbates existing social disparities.

African Americans bear a significant burden of the disease and resulting fatalities. As CNN contributor Van Jones put it, "It's an epidemic jumping on top of a bunch of other epidemics already in the black community." St. Louis city illustrates this very conundrum. Like COVID-19 today, the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic occurred at a pivotal moment in St. Louis history, not only in terms of public health policy, but also in terms of municipal race relations. While St. Louis led the nation in implementing "social distancing" policy in 1918, it contributed to a retrenchment of racial policy fueling the implementation of racial segregation. This century-long history, between 1918 and 2020, has contributed to COVID-19 hitting those traditionally marginalized communities extra hard.

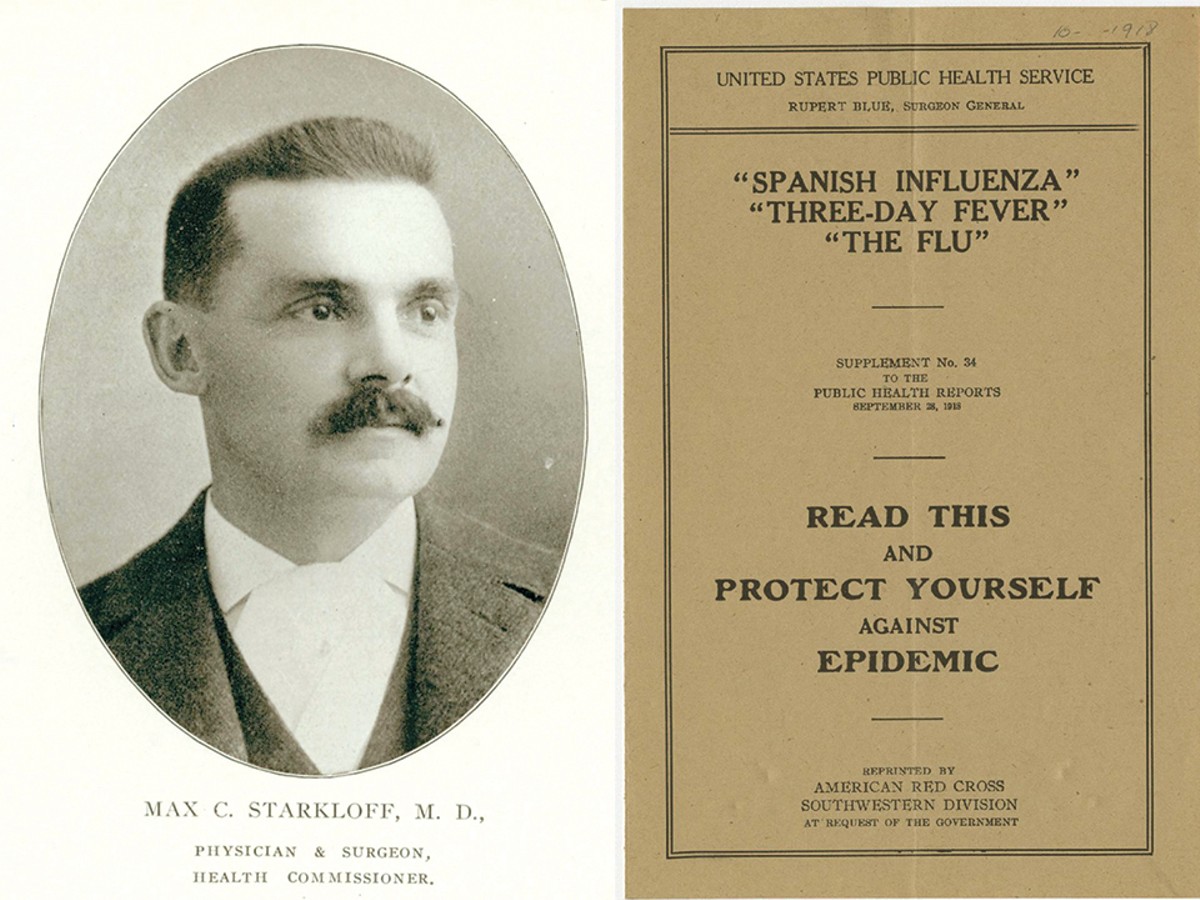

The Spanish flu pandemic, of unknown national origin, was similarly seen as a "great equalizer" and remains the prominent comparison point for the contemporary COVID-19 outbreak more than a century later. That early-twentieth-century crisis impacted tens of millions around the world, as the "Great War" came to a close. Among major cities in the United States, St. Louis was the most effective at reducing the flu's fatalities. This was due, in large part, to Health Commissioner Dr. Max Starkloff, who worked with city administrators and special interests to implement a policy of social distancing. Schools and businesses were shuttered. Police enforced distancing. And when cases surged after social distancing was lifted, Starkloff re-implemented the policy, avoiding more fatalities in the pandemic's second wave.

While this historical case demonstrates that social distancing works, even today's coverage neglects the impact of that policy on African Americans. Medical historians, like George Washington University Professor Vanessa Gamble, have noted that African Americans did not succumb to the flu at the same rate as other Americans. But the Spanish flu had a long-lasting social impact on African Americans in St. Louis and across the nation. In the years before the Spanish flu hit, African Americans had begun to leave the South in large numbers, making their way to other regions of the country. St. Louis saw its African-American population rise significantly. Between 1910 and 1920, St. Louis' non-white population rose by 59 percent according to U.S. Census data. And in terms of health care access, the city was far from prepared for the influx. Municipal facilities and infrastructure were overwhelmed — including the city's public hospital. Black St. Louisans obtained hospital care in the colored wards of City Hospital No. 1 or in the private People's Hospital, if they were hospitalized at all. Frustrated with the lack of access to health care, black elites and health professionals began in 1914 to argue for a negro hospital.

Industries depended on healthy laborers, yet many white St. Louisans feared that germs knew no color line. In 1916, St. Louisans voted to support racial segregation ordinances as backlash against African Americans rose all across the region. (The United States Supreme Court later deemed ordinances like St. Louis' unenforceable.) The 1917 East St. Louis race "riot" subjected hundreds to racial violence. The pandemic fueled racial segregation policies, the effects of which have led to African Americans' disproportionate experience of COVID-19 more than a century later.

It is no coincidence that the precursor to Homer G . Phillips Hospital, City Hospital No. 2, opened in 1919 — expanding African Americans' access to segregated hospital facilities at the tail end of the flu's second wave. St. Louis City Hospital No. 1 was later renamed Max C. Starkloff Memorial Hospital in 1942, shortly after the pioneering public health official passed away.