VU PHONG

In the foreground, the undeniably historic Southwestern Bell Building, built in 1926 with 17 individual roofs. Behind it, the less historic AT&T Tower, built in the 1980s.

St. Louis ranks as one of the premier architectural cities in America, with no fewer than 439 landmarks honored on the National Register of Historic Places.

This is not the time to cheapen that legacy.

A proposal sits before the National Park Service to add an unacclaimed, vacant downtown St. Louis skyscraper from the forgettable 1980s to its registry. That would be the AT&T Tower, a.k.a. One Bell South, a 44-story, 1.4-million-square-foot monument to miscalculation.

The building opened in December 1984 (though construction wasn’t completed until 1985) as the business community — ruled by Civic Progress — mined for fool’s gold with its obsession for new downtown construction. Their accompanying disregard for St. Louis’ history resulted in the destruction of some wonderful historic buildings.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch

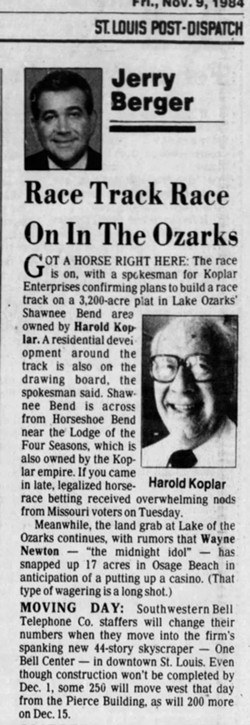

Publications around town have different dates for the completion of the AT&T Tower. But in this November 1984 column from Jerry Berger, it seems the tower had tenants in 1984.

By 2017, when the last departing AT&T employee had turned off the lights (by then, the companies had merged), the former One Bell South had become a white elephant. It’s sat vacant since.

This was a fine building for its time, designed by the internationally famous design firm HOK. The firm was in part helmed by Gyo Obata, who passed away March 8, leaving a wondrous legacy. The fact that a building is connected to a master of his stature is relevant to any future designation as historic.

But the National Register of Historic Places has an age requirement for admittance. It’s stated quite clearly on its website:

“Generally, properties eligible for listing in the National Register are at least 50 years old. Properties less than 50 years of age must be exceptionally important to be considered eligible for listing.”

By that standard, the AT&T Tower needs to get carded. The large majority of those 439 buildings already on the register met the 50-year standard, and the rare exceptions — such as the Gateway Arch — were obviously exceptional.

Thirteen years from now, this former telephone-company office building might present its debatable case for admission, premised largely on being one of HOK’s downtown designs in St. Louis. But the Metropolitan Square Building (in 2039) and the Thomas F. Eagleton Federal Courthouse (in 2050) could argue admission on the same premise.

For now, the AT&T Tower only fits the category “exceptionally important cautionary tales.” It was constructed at a cost of $150 million in 1985. That amount was the equivalent of $358 million in 2019 — the year the building was acquired for $4.1 million. As of that point, it was valued at 1.15 percent of what it cost to build. It was a colossal disaster.

The financial reality is not technically disqualifying, but it hardly cries out “Make an exception for this building!” So why the rush to haul this Titanic to the boat show?

That’s where the story gets murky. You’re never going to believe this, but I think it has to do with money.

Getting listed on the National Register of Historic Places is an honorary thing. Contrary to popular belief, the designation neither protects a building nor impacts how it can be used or renovated going forward.

But the honor does come with one crucial benefit: It’s a prerequisite to qualify for a wide range of federal and state historic tax credits. These are make-or-break for many worthy projects.

Since many historic tax-credit programs — such as the one in Missouri — have their total capped annually, one project’s gain can mean another’s loss. For example, any dollar wasted on, say, an unqualified 37-year-old skyscraper is a dollar not going to support any of the truly historic buildings — large and small — that deserve it more.

In that context, it’s quite puzzling that AT&T Tower has become a favorite of the Missouri State Historic Preservation Office. So much so that it requested that the St. Louis Preservation Board approve its nomination for the national register, according to the St. Louis Business Journal.

The local board then gave its approval “without discussion” at a June 27 virtual meeting, the newspaper added. Call me crazy, but I’d like to know why this dubious application has become so important to preservation officials.

The tower isn’t even owned by a Missouri interest. It was sold on April 25 to a limited-liability company affiliated with the New York-based developer SomeraRoad. The company hasn’t seemed effusive about the building’s future. Here’s more from the Business Journal:

“SomeraRoad has declined to talk publicly about its plans for One Bell Center. But the developer has a history of pursuing historic tax credits for its redevelopment projects. Earlier this year, the firm sold another former AT&T office building, the Ohio Bell Building in Cleveland, to an investor after landing historic tax credits that will help convert the former office tower into apartments. That building, constructed in 1983, was listed on the National Register as part of a broader historic district that was granted official status last year.”

Now that sounds helpful to Missouri. Nothing like having a New York company swoop in, buy our white elephant for a song and flip it for a tidy profit. And did I mention the part about worthier historic projects here missing out on tax credits?

It turns out, however, that perhaps we in St. Louis shouldn’t believe our lying eyes. Rosin Preservation, a Kansas City firm that specializes in presenting proposals like the one at hand, assures us that AT&T Tower is far more special than any of us knew. Here’s what Rachel Consolloy, a preservationist at Rosin, told the Business Journal:

“’This is an important building in [HOK's] portfolio as an early expression of Post-Modernism,’ Consolloy said. ‘One Bell Center embodies three design principles commonly associated with Post-Modernism, particularly contextualism. For example, the stepped top of One Bell Center is a subtle reference to the earlier Southwestern Bell building on the adjacent block and shows how HOK expertly used the surroundings to inform design.’”

I like that style. Let me just say that in the rationalizations mischaracterizing the building, one can see embodied an early expression of the three Post-Modern principles of avoiding accountability: deny, deflect and diffuse.

Speaking of Rosin, I found it interesting that its sophisticated report on behalf of the building seemed to come forth so quickly relative to the April 25 sale to SomeraRoad. So, I contacted the company this past Friday. Amanda Loughlin, Rosin’s national register and survey coordinator, told me that, indeed, a project like this was a year or more in the making.

I asked directly who had hired Rosin to advance the AT&T Tower’s cause. Her response: “No comment.”

This is an unusual story.

Might I throw in that one of the building’s major liabilities is that it has no parking? Or perhaps I should say, “It’s an important example of the 1980s genre of buildings whose owners lacked the foresight to include parking in a freaking downtown skyscraper.”

One fix, albeit a quite expensive one, might be to invest in converting the bottom 5 to 10 floors for parking. It’s not impossible and might be the only way to attract a big company to take over the giant building.

But guess what sort of thing you likely cannot do with a historic building if it receives historic tax credits? Yep, a project like that one. There’s something funky going on here.

All we know for sure is that when it comes to historic preservation, St. Louis is exceptional. And the phone company’s deserted white elephant is not.

Ray Hartmann founded the Riverfront Times in 1977. Contact him at [email protected] or catch him on Donnybrook at 7 p.m. on Thursdays on the Nine Network and St. Louis In the Know With Ray Hartmann from 9 to 11 p.m. Monday thru Friday on KTRS (550 AM).