In case you missed the news over the weekend, Quebec is having a bit of a problem with hardcore criminals escaping prison by helicopter. On Saturday, a green-colored chopper landed in the courtyard of a detention center in suburban Quebec. It took off with three inmates, two of whom are facing murder charges.

The escape is Quebec's second daring helicopter prison break in two years. In March 2013, a helicopter pilot was forced at gunpoint to hover over a different prison while two inmates shimmied up rope ladders.

This got us thinking: Somebody has to tell Quebec about Allen Barklage.

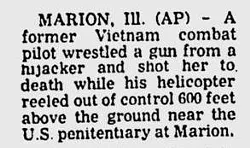

A former Vietnam combat pilot, Barklage nearly died on May 24, 1978 while foiling a passengers' attempt to hijack his helicopter for a prison break in Marion, Illinois.

See also: Nunchuck-Wielding Inmate Fends Off a Dozen Corrections Officers, Escapes Jail

The Associated Press story from May 25, 1978 has all the makings of kick-ass action movie finale: There's Barklage in the cockpit, wrestling a .44 caliber pistol from the hands of a middle aged woman, killing her, righting the helicopter and landing 70 feet from the prison administration building.

The hijacker was 43-year-old Barbara Ann Oswald. She had hired Barklage to fly her to Cape Girardeau to look at real estate, but 30 or 40 minute into the flight she pulled a gun on him and ordered him to fly to the federal prison in Marion, a maximum security facility built to replace Alcatraz Island.

Oswald had fallen in love with a Marion inmate named Garrett Trapnell. In 1972, he made headlines for hijacking a TWA flight from Los Angeles to New York. After his arrest, Trapnell befriended another Marion inmate, Martin McNally, who in 1972 had also hijacked a passenger plane, this one flying from St. Louis to Tulsa, Oklahoma. The two hijackers and a third accomplice were waiting for Oswald on the roof of a one-story cellhouse.

According to the AP story, Barklage bided his time until he noticed Oswald place her finger on the trigger guard, not the trigger, of her pistol. The next moments were pure chaos:

"I let go of the helicopter controls and let it do whatever it wanted," [Barklage] said. "I grabbed for the gun and we had a 10- or 15-second struggle."The Jetranger II helicopter was pitching and turning wildly, he said. It was so erratic that "that I shot four times...shot all five times but one misfired -- and I only hit her once. And she was only two feet away from me."

The story made Barklage a hero, but attempts to free Trapnell didn't end there: In 1978, Oswald's 17-year-old daughter hijacked her own TWA flight and threatened to blow up the plane with dynamite strapped to her chest. She demanded Trapnell go free. FBI negotiators managed to free the hostages, and the teenagers' dynamite turned out to be road flares.

As for Barklage, he went on to save a man from attempted suicide in 1991 by plucking him out of the Mississippi river beneath the Poplar Street Bridge. KSDK covered the rescue and recapped Barkage's earlier heroism.

Barklage's story has a tragic postscript. He died in 1998 after an experimental mini copter malfunctioned shortly after take off.

So Quebec, we understand what you're going through. And one thing is for certain: the world needs more quick-thinking, fearless flyers like Barklage.

Follow Danny Wicentowski on Twitter at @D_Towski. E-mail the author at [email protected]