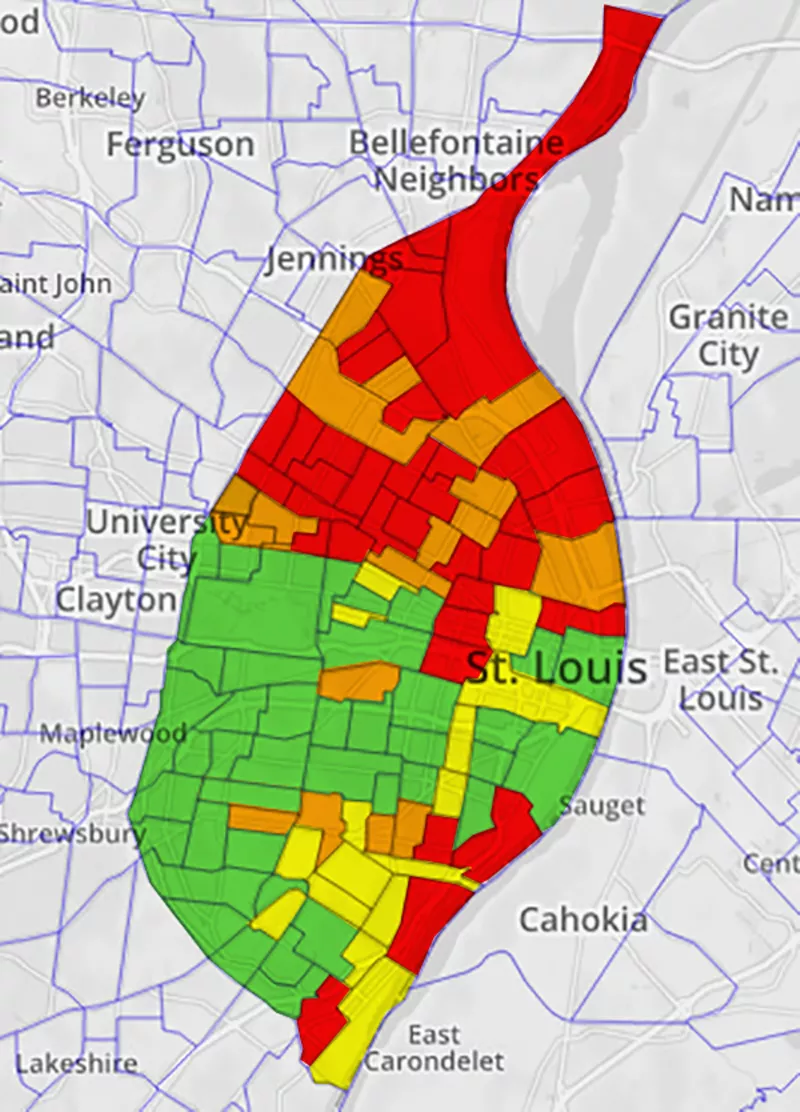

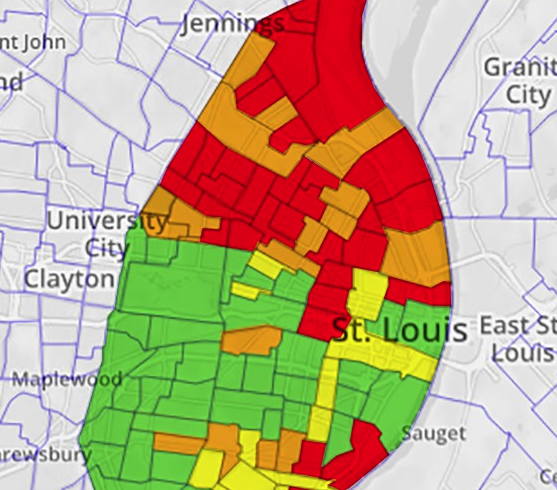

ILLUSTRATION BY EVAN SULT

Areas north of Delmar show little Internet connectivity. See a complete map, and our key, below.

The Delmar Divide is also a digital divide. According to an analysis of data recently released by the U.S. Census Bureau, St. Louisans’ access to the internet differs drastically north and south of the boulevard.

Released in the last weeks of 2018, the Census Bureau's 2013-2017 American Community Survey for the first time includes highly specific information about who has access to the internet and who doesn’t.

According to the survey, of the roughly 36,000 St. Louis city households north of Delmar, about 16,000, or 44 percent, have no internet access at all. An additional 3,000 have access only via cellular data. Crunch the same numbers for the 101,000 city households south of Delmar and the percentage of those that are unconnected drops by more than half to 20 percent.

The areas of poorest coverage, what are sometimes called digital deserts, include swaths of the O’Fallon, Penrose, Wells Goodfellow, Mark Twain and the Greater Ville neighborhoods. An older population by no means explains this lack of connectivity in these areas. According to the survey, the average age in the city as a whole is a little over 35; in these digital deserts the average age is less than 38.

Missouri comes in 41st of all states in terms of connectivity, according to consumer education organization BroadbandNow. Areas in rural Missouri struggle with a lack of high speed access as well. In April of 2017 then-Governor Eric Greitens pledged $45 million in state funding for rural high speed access.

Justin Idleburg is a resident of the 26th Ward, which straddles Delmar. A board member of Forward Through Ferguson and a Community Catalyst of Equity & Innovation for Nehemiah’s Mission St. Louis, he says the digital divide in St. Louis has long been a concern of his, particularly in the schools. He reads about schools elsewhere in the city giving students internet-connected tablets, but has yet to see that happen in his community.

“I don’t want to see kids here be part of any divide,” Idleburg says. “We can’t bring business in. We can’t bridge the wealth gap or address anything else in regard to upward mobility if the kids aren’t equipped with what they need to excel. Kids don’t have access to the necessary tools and resources that allow them to compete not just locally but in global markets we push them to be a part of.”

Most households in north city have a choice between AT&T or Charter, though in some spots one of the companies is the sole option. The cost of coverage runs, at minimum, $45 a month, according to BroadbandNow. This is not an insignificant cost considering that in the least connected areas of the city, more than one in three people reported earning an income in the past twelve months that was below the poverty level, according to the Census Bureau survey.

The St. Louis Public Library is one organization trying to ameliorate the effects of St. Louis’ digital divide. Spokeswoman Jen Hatton says that every year the computers, laptops and WiFi at the library's sixteen locations are used 2 million times to access the internet. Additionally, the library offers mobile hotspots for patrons to check out and bring home.

Last year Sprint donated tablets and wireless service to 1,000 St. Louis public school students. AT&T offers internet at a reduced speed to some low-income households for $10 a month. Still, in some parts of St. Louis nearly two out of three households remain unconnected.

“I define literacies, plural, for today’s world,” says Shea Kerkhoff, an assistant professor of secondary education at the University of Missouri-St. Louis. “The way we communicate and receive information today is digital, so in order to be fully active participants in democracy, in our community, in college and in careers, we need digital literacy.”

Kerkhoff says students without internet access at home are severely disadvantaged in this regard, though the effects are not always apparent in the short term.

Many teachers adapt to the digital divide in their classrooms by instructing students who have home internet access to complete an assignment one way and telling those who don’t to complete the homework in an alternative way. At the end of the semester students in both camps might get the same grade, but the students without the internet at home don’t get the digital-literacy practice.

The disadvantages of living in a disconnected household don't end at high school graduation, says Kerkhoff. “People need access to the internet to apply for college, to apply for scholarships, to apply for jobs.”

The above map shows the percent of households with no access to the internet, color-coded by census tract.

Green: 30 percent or less

Yellow: 31 to 40 percent

Orange: 41 to 50 percent

Red: 51 percent or more

All data from the Census Bureau's 2013-2017 American Community Survey. Illustration by Evan Sult.