On December 8, an avalanche of emails from aspiring informants poured into the office of Missouri Attorney General Eric Schmitt. By the end of the next day, the collection of emails ran more than 8,000 pages.

Schmitt had put out an open call for parents who could feed him information about masking policies at Missouri’s public schools. A Riverfront Times review of the resulting emails from its first two days day of operation reveals the extent to which Schmitt’s office sought out potential plaintiffs for his future lawsuits.

Parents rushed to provide accounts of school districts that refused to end public health orders. As the emails also show, their reactions went further: Some parents described sending their children to school in the belief that the mandates had already ended, and with the expectation that Schmitt’s edict had the force of law — only for those students to be pulled aside and sent home.

Indeed, while Schmitt maintains that a 2021 ruling by a judge in Cole County made schools’ COVID-related health orders “null and void,” most school districts targeted by Schmitt’s demands have maintained their mandates, with some arguing that the judge’s ruling was limited and cannot erase the authorities given to school districts under state law.

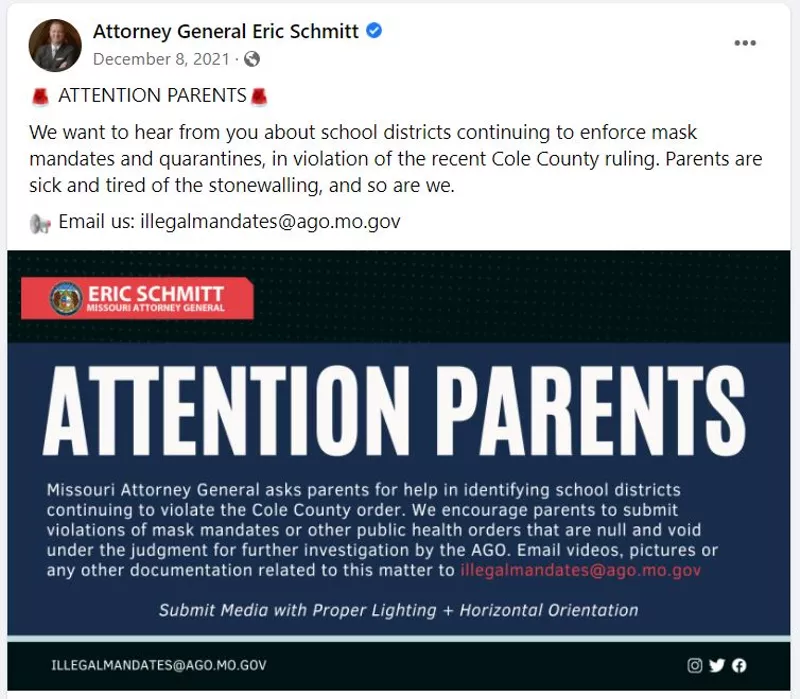

Initially rebuffed, Schmitt then sent 52 school districts cease-and-desist letters and, one day later, announced that his office had created a dedicated “Illegal Mandates” email address as a resource for “further investigation” of the schools. The first responses landed in the inbox on the afternoon of December 8. Thousands followed.

The inbox’s first days of operation — between December 8 and 9 — seemed to prove most fruitful for Schmitt: Of the 110 parents named as plaintiffs in the recent wave of lawsuits Schmitt filed against nearly four dozen Missouri schools, 45 had sent emails to the Illegal Mandates inbox, records obtained by the RFT show.

As a tactic, the inbox worked to perfection: Schmitt had put out the call, and his target audience answered. The strategy successfully dug up grievances on school districts and located the parents willing to air them in court.

Some school districts responded with forceful rejections of Schmitt’s demands. The Francis Howell School District released a statement calling the attorney general’s position “tenuous at best” and his actions “disheartening, unfounded, and frankly, shameful.” In Lee’s Summit, attorneys for the school board released an open letter in response to Schmitt that cited the state statute which makes it “unlawful for any child to attend any of the public schools of this state while afflicted with any contagious or infectious disease or while liable to transmit such disease after having been exposed to it.”

The existing law, the letter continued, “speaks for itself.”

But Schmitt persisted. Behind his demands and call for informants was his argument, stated plainly in his cease-and-desist letters mailed to school districts, that he considered it as fact that the Cole County decision made hundreds of school health orders illegal. Schmitt’s office restated this position in its outreach to parents, the claims made in the office’s official social media channels and printed on official letterhead — but facing fierce legal opposition from school districts, Schmitt chose not to wait for the legal system to actually prove his claim.

As the emails make it clear, he didn’t need to. People already believed him. And they were willing to act on it.

SCREENSHOT VIA FACEBOOK

Eric Schmitt's December 8 announcement called for parents to report their schools.

“Didn’t you deem it illegal?”

On December 7, parents already opposed to the mask mandates saw the news of Schmitt’s cease-and-desist letters as a sign that the battle was over. They had won. Naturally, they made plans.

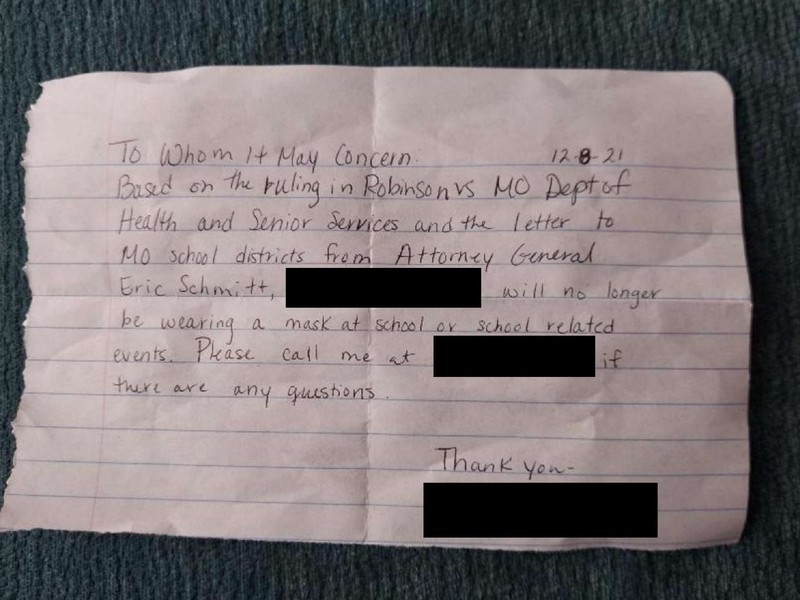

The next day, in Springfield, a mom dropped off two of her children at their middle school with no masks, each clutching handwritten notes that cited Schmitt’s letters and the Cole County ruling, while concluding they “will no longer be wearing a mask at school or school related events.”

But the notes were just paper. The mom was soon called back to pick up her kids, as they had both been dismissed for violating the school’s mask rules. Later that day, she sent a string of anxious emails to [email protected]. She attached photos of the note and an email thread of her arguing with the school’s principal, who had ignored Schmitt’s order and written back to her saying “there will be no change to our mitigation strategies that have served us well since the onset of the pandemic.”

She wasn’t the only one. The email records show the pattern in school districts across the state on December 8 as seemingly dozens of parents took Schmitt as his word.

For the kids of those parents, it was a day of suspensions, dismissals and confusion.

In Columbia, a father contacted Schmitt’s tip line to complain that he had sent his children to school that day with printouts of the cease-and-desist letter, and instructed them that “if they were told to wear a mask to politely tell the teacher that they did not have to wear it anymore and to give them the letter.” Both kids were sent to the principal’s office and given unexcused absences.

It wasn’t just mask mandates being tested. In Washington County, a mom emailed Schmitt about her attempt to send her middle-schooler back to class even though he was on an “exclusion list” after a COVID-19 exposure the previous week.

“I was immediately called and told I needed to come pick him up,” she wrote, and asked Schmitt to file a complaint against the district.

Still, the parents who attempted to bend reality to Schmitt’s interpretation of the law — with their kids as test subjects — did not blame the attorney general for the results, but the schools for not complying. Some wrote to the tip line explicitly seeking action against specific teachers and administrators. Others wanted lawsuits filed and board members removed.

"The superintendent is forcing my children to break the law or suffer consequences,” a mom of two in the Affton school district wrote in her email to Schmitt’s snitch line. “I believe that is illegal.”

A large number of parents who contacted Schmitt’s Illegal Mandates account acted as quiet intermediaries, forwarding announcements from their districts as officials released public responses to the cease-and-desist letters. Another segment of respondents identified themselves as teachers, and the RFT was able to corroborate the employment of more than 30 staff members who reported their own districts to Schmitt.

Yet, in emails to parents and public statements, the districts reiterated that, no matter what the attorney general said, the mask mandates weren’t going anywhere.

In some cases, parents received a form letter back from Schmitt commending them for coming forward — “As a father of three, I know how critical it is to ensure that children receive a quality education,” the official response noted — but for one mom in Liberty School District, a pat on the head wasn’t enough. She wanted Schmitt to tell her what to do.

“Do we continue to send our kids to school with masks? I don’t want to punish them and get them suspended,” she wrote. “I just don’t know what our rights are regarding this situation right now. I feel we are in limbo.” (It doesn’t appear that Schmitt or his staff ever responded.)

Another mom, this one with kids in the Mehlville district, wrote to Schmitt to complain that a school board member had been unwilling to commit to a “mask optional” policy in light of Schmitt’s cease-and-desist letter and Cole County ruling. The situation flummoxed her.

“Why?” she asked in her email. “Didn't you deem it illegal for them to still make and enforce the kids to mask?” She signed her email, “A confused parent.”

Other parents took their confusion and turned it into action. One mom who contacted Schmitt’s Illegal Mandates inbox said she had filed a police report against the Wentzville School Board, which during a December 8 meeting had “openly and blatantly defied your order.” Her email included a police report number and named the officer with whom she submitted the complaint against the board.

Reached by email, an office manager with the Wentzville Police Department confirmed that a police report with that number had indeed been pulled by that officer on December 8.

“However,” their response continued, “it was subsequently determined that no report would be taken.”

MISSOURI ATTORNEY GENERAL'S OFFICE

A note (redacted by RFT) that one mom gave her children on December 8, stating that they do not need to wear a mask.

“COVID tyrants”

While school districts across Missouri found themselves facing parental demands and unmasked students waving cease-and-desist letters, Eric Schmitt wasted no time in touting the results of his efforts.

In the days after the snitch line’s debut, Schmitt’s social media pages — including those for U.S. Senate campaign — repackaged the emotional accounts emailed by parents into tidy, sharable posts, each stamped with the logo of the Attorney General’s Office and a hashtag, #NoMoreMandates. When it came to school districts, Schmitt was on a warpath, filing new cease-and-desist letters and posting screenshots of emails received from parents despairing that their children had been isolated from other students or dismissed after refusing to wear masks at school.

Schmitt leaped to count his victories. On December 8, he shared a news story detailing how the public school district in Marshall ended its mask mandate. One day later, he shared a screenshot of emails sent by the Meramec Valley and Odessa districts to parents announcing that their respective masking requirements had been eliminated.

“COVID tyrants have gotten used to using fear to control people,” Schmitt posted on his campaign Facebook page on December 10. “They don’t like it when people fight back. That’s happening now. Freedom will win.”

That day, for Schmitt, it may have seemed like all the pieces were falling into place. Parents had willfully offered their own children to test his legal demands, and the negative consequences for those students had only further enraged his volunteer army. With more than 100 parents willing to put their names on lawsuits, he had the ammunition to attack the recalcitrant school districts with lawsuits and more publicity.

And then the omicron wave struck, and all the plots and politics of Missouri’s attorney general couldn’t stop kids, teachers and staff from getting sick. The school districts of Marshall and Odessa, which had followed Schmitt’s edict, were forced to shut down for days earlier this month as COVID-19 cases soared among students and staff. In total, 62 school districts closed in January for at least one day due to staffing shortages amid the surge.

Facing rising COVID numbers, school districts that had adopted mask-optional policies after Schmitt’s legal salvo — among them Rockwood, Lindbergh, Mehlville and Parkway — rescinded those optional plans and made masking mandatory, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported this week.

But Schmitt kept his focus. Even as medical experts and public officials begged communities to stay indoors and reduce strain on hospitals, his office was doing the work of assembling its harvest of parents-turned-plaintiffs — people who were, apparently, unbothered by the path that took them to this position.

Outside, in their kids’ schools, in their local hospitals, the reality of COVID-19 was all around them.

Instead, they opened their email inbox and hit compose.

Follow Danny Wicentowski on Twitter at @D_Towski. E-mail the author at [email protected]