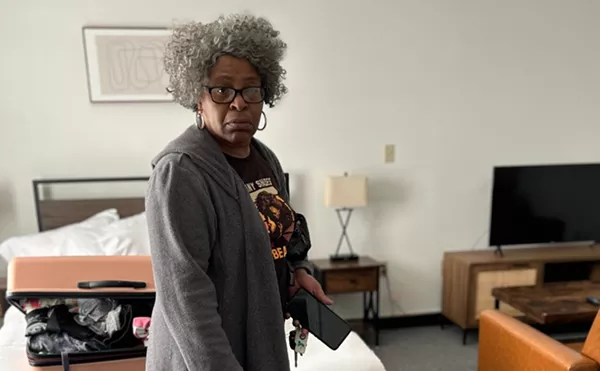

When it comes to the St. Louis County Pet Adoption Shelter Center, no person is more demonized and defended than Beth Vesco-Mock.

Hired by Stenger in September 2017, Vesco-Mock had spent the previous decade as the director of the Animal Service Center of the Mesilla Valley in New Mexico, where she had turned heads with her impressive results lowering euthanasia rates. As she told one local newspaper there, she had transformed a shelter from a "slaughterhouse" to one with "a culture of life."

From certain angles, Vesco-Mock was the perfect candidate for St. Louis County. She also seemed to tick the important boxes for Stenger, who sought to fulfill his 2014 campaign promise to lower euthanasia (and thereby wring more political capital from his supporters in the animal welfare community.) For members of the shelter's advisory board, who yearned for a director with genuine animal shelter experience, Vesco-Mock was exactly the sort of "animals first" leader they'd been waiting for.

At first, she seemed just as advertised: Almost immediately, the euthanasia rate plummeted, making Vesco-Mock allies on the advisory board. But the new director made a disastrous impression on the staff, and the accounts of one particular racist incident would follow her for months, ultimately sealing her termination.

Starting in early 2018, shelter volunteers and staff began contacting RFT to complain about Vesco-Mock. Amid allegations of mismanagement and overcrowding, multiple sources referenced details of an incident in which Vesco-Mock, they said, had told a group of black employees to get back to work and to stop "gangbanging."

One employee, who requested anonymity to protect his current position in the shelter, claims he witnessed the incident, which he says occurred during a kennel staff meeting "not long" after Vesco-Mock's hiring.

"I was part of that group," the staffer tells RFT. "We was all in the hallway, and she said, 'Stop gangbanging in the hallway.' She just said it. It was the wrong thing to say."

Afterward, the employee says, black staffers in the group discussed the incident, and "took offense."

"We all had this confused look. We weren't angry, but confused. We're colored people, and what she said, we just don't do that. That's how I took it. After that, people started quitting left and right."

In a matter of weeks, the "gangbanging" comment had hit the shelter's grapevine, and volunteers began emailing reporters and showing up at county council meetings to complain about the new director.

Harmony Collender, an animal caregiver at the shelter who was hired in early 2018, says her first impression of the workplace was that "no one liked" Vesco-Mock. Collender claims she witnessed the director going out of her way to "act disrespectful" to a supervisor, "just putting him down, in front of me, when he hadn't done something as quickly as she wanted him to."

Eventually, employees filed complaints against Vesco-Mock, leading to meetings with representatives of the county HR department. Similar complaints became weekly features at the county council meetings, where a core of activists and volunteers not only pleaded on behalf of the animals, but begged the county to save the staff from Vesco-Mock's racism and shelter mismanagement.

But Vesco-Mock had the support of Stenger, who seemed entirely pleased with his director's impact on the shelter.

In January 2018, the shelter reported a dazzling live-release rate of 97 percent, a newsworthy announcement that brought a KTVI (Channel 2) reporter and camera crew to document the shelter's animal-saving successes. The story featured Stenger praising the adoption numbers, with Vesco-Mock taking credit for changing the shelter's "culture."

"We made a culture change here," she explained, "from a culture of keeping them comfortable until they were euthanized, to keeping them comfortable until they find a home."

There was another side to Beth Vesco-Mock, a history she likely hoped to have left behind when she arrived in St. Louis.

But news travels, and one week after Stenger and Vesco-Mock made their televised victory lap around the shelter's live-release rate, RFT became the first local outlet to publish details on Vesco-Mock's scandal-scarred career as shelter director in Mesilla Valley, about 50 miles from the border in southern New Mexico.

In July 2017, after nine years running the Mesilla Valley shelter, Vesco-Mock surprised local officials by tendering her resignation. According to local news reports, the decision followed months of conflict, which had spilled into emotionally charged hearings before the city council. Earlier that year, a former employee had leaked photos of the Mesilla Valley shelter to local media, showing filthy conditions and sick dogs. Two weeks later, Vesco-Mock was caught in a different scandal, admitting that she had allowed a drug company to administer experimental diarrhea medication to some of the shelter's dogs. (She insisted it was standard practice and that no animals were harmed.)

And as in St. Louis, Vesco-Mock was accused of racism. According to the minutes of an April 2017 hearing held by the Las Cruces City Council, a former shelter employee charged that Vesco-Mock was a "racist, bigoted pig" who had driven away sixteen employees.

The summer of 2017 would be Vesco-Mock's last in New Mexico. One month after tendering her resignation at the Mesilla Valley shelter, she packed up her family and moved to Missouri.

For both for Vesco-Mock and St. Louis County's shelter, it was an opportunity to do something different. That opportunity ended in dramatic fashion when Steve Stenger fired her.

On February 27, 2018, Beth Vesco-Mock, accompanied by her private attorney, faced a hearing over her leadership of the shelter. For weeks, county council members had listened to volunteers and staff members describe a shelter struggling with overcrowding, disease and human dissatisfaction. Now they wanted to hear directly from her.

Vesco-Mock was not without supporters. At the hearing, two advisory board members spoke on her behalf, including Ellen Lawrence, who had previously emailed RFT to defend Vesco-Mock's success in lowering euthanasia rates, an accomplishment that, Lawrence wrote, "should be cause enough for celebration."

At the hearing, though, Vesco-Mock's defense faltered under the grilling from the council. Though she had earned a degree in veterinary science from Ohio State University, at one point she was forced to correct her introduction as "veterinarian," acknowledging that she had actually never been licensed as a veterinarian in either New Mexico or Missouri.

That may have been the least of her issues. According to coverage of the meeting reported by Call Newspapers and the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Councilwoman Hazel Erby put the question of racism directly to Vesco-Mock, saying, "We have had complaints that you have made some racist statements, and that concerns me."

This was the first time Vesco-Mock had ever been asked to publicly address the alleged "gangbanging" comment, as well as a related accusation that she had been known to express a preference for "crackers" over black people.

In response, Vesco-Mock's lawyer reportedly whispered something in her ear, and she declined to answer. Instead, she responded to Erby, who is black, saying only that, "I can guarantee you, ma'am, that diversity has never been an issue in my life."

Three weeks later, citing "inappropriate conduct" and "a number of matters relating to the current management of the shelter," Stenger announced he had fired Vesco-Mock.

Stenger didn't release specific reasons for the termination, but he still said enough for staff to recognize the echoes of their complaints to the county's HR department. In a later interview with St. Louis Public Radio, Stenger commented of Vesco-Mock's behavior, saying, "Racist or discriminatory behavior is not going to be tolerated by this administration."

But Vesco-Mock wasn't rattled, and she didn't back down from Stenger. In fact, this wasn't the first time she had come under serious fire: In 2015, prosecutors in Doña Ana County, New Mexico, had charged her with multiple misdemeanors for refusing to hand over a dog's microchip to an animal control officer. In the end, the charges were dropped mid-trial, and Vesco-Mock turned around and sued the Doña Ana County Sheriff's Office for "malicious abuse of process and defamation of character." The sheriff's office settled the case, agreeing to pay Vesco-Mock $90,000.

In St. Louis, things once again shook out in Vesco-Mock's favor. Two months after her termination, her lawyer filed an employment complaint against Stenger, alleging Vesco-Mock was the victim of gender discrimination.

In January 2019, the county announced that it would pay $150,000 to settle the complaint with its fired shelter director. Neither the county nor Vesco-Mock admitted wrongdoing and both agreed not to disparage the other. She agreed never to work for St. Louis County again.

Reached by phone in September, Vesco-Mock's attorney, Edwin C. Ernst, said both he and his client were bound by a confidentiality agreement and could not discuss the shelter. Last year, however, in an interview with St. Louis Public Radio, Ernst did admit that his client had told a group of shelter employees, "Guys, we can't have any gangbanging in the hall here" but he insisted that she had not intended it as a racist statement.

To RFT, Ernst noted that Vesco-Mock has lost much since her firing. "This was her life, she loved working with animals, she got caught up in the whole thing, and unfortunately today she's not able to do that anymore. This was very sad for her, very traumatic for her."

Vesco-Mock still lives in the St. Louis area, Ernst says. She has taken a new job as a corrections officer.