In late June, a gunman slipped into a beloved black church in Charleston, South Carolina, and massacred nine people who had met for Bible study.

The slaughter of innocents in a house of worship garnered news coverage across the country, and reporters from the nation's most powerful media organizations began working through a familiar checklist: How many were dead and how many had been injured? Who was the killer? And, perhaps most importantly of all, what was his back story? People always want to know why.

Dylann Roof, a scrawny white guy with a bad haircut, quickly emerged as the prime suspect, but that only led to more questions. Roof was apparently a racist, but plenty of those don't open fire in a church. What had triggered his murderous rampage?

Then a young journalist with St. Louis roots landed a big scoop.

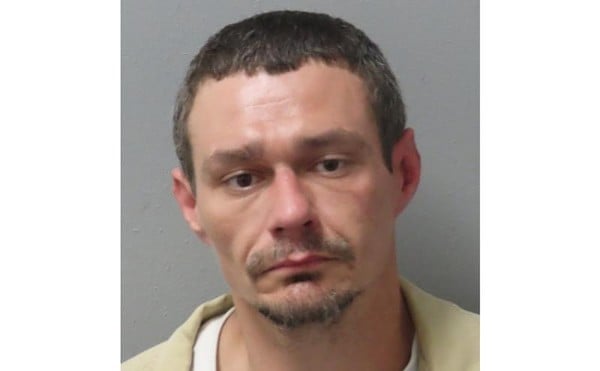

Juan Thompson, a 30-year-old rookie reporter for online news site the Intercept, claimed he'd landed an exclusive interview with Roof's cousin Scott and that he could trace the fury that fueled the carnage.

"Scott Roof, who identified himself as Dylann Roof's cousin, told me over the telephone that 'Dylann was normal until he started listening to that 'white power music stuff,'" Thompson wrote in a story that went live at 11:05 p.m. on June 18. "He also claimed that 'he kind of went over the edge when a girl he liked started dating a black guy two years back.'"

ABC News had previously spoken to Dylann Roof's roommate, who'd claimed the shooter had talked about plans for racial violence, but the narrative of a jilted lover seeking revenge was a juicy new wrinkle.

"Dylann liked her," Scott Roof said, according to Thompson. "The black guy got her. He changed. I don't know if we would be here if not..."

In Thompson's telling, the interview ended with a dramatic flourish as the cousin broke off in mid-sentence and hung up the phone.

News agencies across the country were soon citing the Intercept's exclusive as they raced to cobble together a picture of the gunman.

There was only one problem. It was a lie. Scott Roof doesn't exist, two relatives later told the Intercept. And a story-by-story review of the young writer's work ultimately convinced the site's leadership that the cousin had been only one of Thompson's inventions.

The article was part of a "pattern of deception" that spread across a number of his posts, Betsy Reed, the site's editor in chief, charged in a damning February 2 editor's note.

"Thompson fabricated several quotes in his stories and created fake email accounts that he used to impersonate people, one of which was a Gmail account in my name," Reed wrote.

The bombshell accusations left anyone who'd ever worked with Thompson wondering if he'd scammed them too. It's a tricky question to untangle, noted Josh Marshall, the editor and publisher of the liberal online publication Talking Points Memo, which had published one of his essays.

"One of the dirty little secrets of fact-checking," Marshall wrote in an editor's note, "is that it is quite difficult to uncover a determined effort to deceive."

Even more than plagiarism, fabrication is the ultimate sin of journalism. Taking credit for someone else's work will probably get you fired. But selling fiction as fact invites pariah status.

Famous fabricators Stephen Glass of the New Republic and Jayson Blair of the New York Times were rising stars before they were ejected from the news business for inventing their material. Now Glass, who graduated magna cum laude from Georgetown University's law school, can't even get licensed as a lawyer because of his history as a dishonest journalist. Blair works as a life coach in Virginia.

But even as those two writers became nationally infamous for their sins of fabrication, Thompson's errors would arguably have a wider impact. That's less about the publication he worked for and more about the nature of journalism in the digital age. These days, everyone is rapidly repurposing stories from somewhere else, slapping on web-friendly headlines and trying to turn them into pageviews.

As Washington Post media critic Erik Wemple noted, Thompson's Scott Roof "scoop" was cited by the New York Daily News, New York Post, New York Magazine, Toronto Sun, Alternet, the Root, Radar Online, Latin Post, Centric TV and even the U.K.'s Indy, Daily Mail and Mirror — and that's likely an incomplete list.

The alleged hoax prompted chagrined editors from the fooled outlets to write their own correction notes or, in some cases, to simply erase the stories from their digital archives as if the whole messy business never happened.

"In addition to the obvious lessons about editing, the Thompson story yields some notions about the psychology of aggregation," Wemple wrote. "Read the editor's notes above from organizations that followed up the Intercept's work: They don't apologize for having failed to vet the story and instead just drop the blame on the Intercept."