But inside, around the corner and down the hall, pull away a thick wooden door, then another. Somewhere between 80 decibels and intolerable, a would-be pop-crunk anthem pounds:

We came to get it poppin'

We came to get it crackin'

Sipping Cognacin'

And rollin' Cadillacin'

Alonzo "Zo" Lee Jr. and Shamar "Sham" Daugherty's 80 G's worth of matching diamond-encrusted, star-shape necklaces bounce, ever so slightly, in time to the heavy bass. The duo, collectively known as the Trak Starz, look out over a million and a half bucks' worth of equipment, pondering which of a hundred thousand little knobs need to be twisted. NASA engineers come to mind -- except NASA engineers probably have less at stake than Lee and Daugherty. NASA engineers merely have to find water on Mars using a mechanical gizmo. These guys have to find hooks using mechanical pop stars.

Blackground, the division of Universal Records responsible for hits from Aaliyah and Missy Elliott, is betting $450 an hour they can. That's about how much it costs to staff and run this room, to say nothing of the Starz' production fee.

"Can I hear it with the 808?" Lee asks, tugging the blue Von Dutch cap that covers his braided dreadlocks.

"I think it's hot," says Daugherty, who sports a Joe Morgan Cincinnati Reds jersey and a red mesh trucker hat with "Trak Starz" emblazoned on the front. "I think the bass still needs to be in that one part, though."

An engineer turns a dial. Done.

The song, "Poppin' in the Place," by Kentucky pop-crunk artist Native, will likely be on the radio in a month or so. But unlike many hip-hop producers, the Starz aren't using a sample of someone else's song to construct the beat; instead they're grafting on a progression they crafted themselves in the studio, labor that will keep them at work till 2 a.m. on this late-February night.

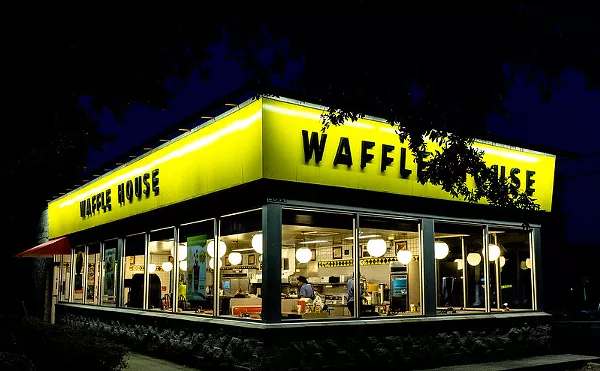

"You guys wanna eat?" asks Daugherty, scanning a takeout menu from Roscoe's Chicken and Waffles.

After they finish the night's work, the Starz will cruise their rented Sequoia back to Le Meridien, their well-north-of-$200-per-night hotel in Beverly Hills, have some drinks and snacks from the mini-bar, and watch cable. All on Blackground's tab. Tomorrow they've got a meeting scheduled with Jimmy Iovine -- the Interscope Records president renowned for his work with Patti Smith, Tom Petty and U2 (and infamous for his work with Death Row Records) -- with whom they'll negotiate what they say is a six-figure deal to produce Eminem, Eve and 50 Cent.

This, in addition to work they've already got scheduled for rival industry giant Sony.

Vincent Herbert, an industry veteran here representing Blackground, forgoes the chicken and waffles but attempts to explain why, when it comes to the Starz, so many labels are lining up to pony up.

"They're the next Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis," he says, referring to the celebrated Minneapolis production team. "They're visionary guys, not just making beats. They develop artists, and people just don't do that anymore. That's what they did with Chingy."

The St. Louis hip-hop scene was sparked at the turn of the millennium by Nelly and the St. Lunatics. Four years later, it's on fire. Last week, no less a cultural authority than The New Yorker weighed in. "The atmosphere in St. Louis is now a little like that of Nashville in the nineteen-thirties, with the Grand Ole Opry, or of Detroit in the sixties, with Motown Records," the New Yorker's Jake Halpern writes in a feature about Mark "Tarboy" Williams and Joe "Capo" Kent, a pair of local producers known as the Trackboyz, who discovered local wunderkind J-Kwon and produced his current No. 3 single "Tipsy."

Although they're not yet household names along the lines of the Neptunes, Timbaland and Dr. Dre, just about anyone who listens to FM radio is familiar with the hits the Starz produced for Chingy: the lovingly exploitive-of-the-St.-Louis-accent "Right Thurr" ("I like the way you do that right thurr/Swing your hips when you're walkin', let down your hurr"); "Holidae In," featuring Snoop Dogg and Ludacris; and "One Call Away," whose video features grown-up Cosby kid Keshia Knight Pulliam and the Trak Starz themselves. The Starz also remixed Britney Spears' and Madonna's "Me Against the Music" and Ludacris' "Splash Waterfalls," the latter of which got nearly as much play as the original. But all that pales next to what they've got in the pipeline: songs starring Beyoncé, Lil' Kim, Toni Braxton, Gwen Stefani and Faith Evans; the scores to the soundtracks of Soul Plane and the Shaft sequel; and their own reality TV show.

The Trak Starz are already rich, and soon they'll be famous. But look beneath the bling, and Lee and Daugherty seem to be less about getting paid and more about battening down a local-music infrastructure that has the hip-hop world by the throat.

Welcome to the St. Louis Hip-Hop Renaissance, Part 2: World Domination.

"What da hook gon be?" Murphy Lee famously asked in his 2003 single of the same name. To say that's the million-dollar question in pop music wouldn't exactly be true -- a good hook is worth much more than that.

Along with the beat, the hook -- a chorus designed to drill itself into your head and refuse to leave until your consumerist obligation has been satisfied -- is the heart of pop music. Think of the most popular songs of the past three decades -- say, "Billie Jean," "Smells Like Teen Spirit" and "In da Club." You probably know all three hooks by heart and have conveniently overlooked their less-memorable aspects (think: "A mulatto, an albino, a mosquito, my libido, yay"). The inventors of those hooks are more famous than the inventors of the Internet, penicillin and the Thighmaster combined.

Movies have directors; songs have producers. In today's pop music, producers dominate the creative process. Even as the music industry is hammered by declining profits, filesharing and layoffs, top producers are getting heftier contracts and greater creative control. Whereas once upon a time Lennon and McCartney may have locked themselves in a room and not come out until they had a hit, nowadays their record label would probably just hire the Neptunes, the Virginia Beach-based duo that's as famous as the stars they work for. They made Justin Timberlake hip, they made Britney a slave for us, and now they command hundreds of thousands of dollars to produce a single song.

Cost-cutting execs want producers who can find talent as well as make music. When the Trak Starz brought Capitol Records Chingy's already finished debut album, Jackpot, Capitol bought it outright. They didn't spend a dime in development.

When the Starz hooked up with Chingy, both were unknown. Now, says Allie-Ryan Butler, coordinator of business and legal affairs for Atlantic Records, "Their success is directly coordinated to Chingy's success. Artists are saying, 'If the Trak Starz can do that for Chingy, then they can do that for me.'"

So profound are record labels' desires for proven hitmakers that they'll tolerate something from the Trak Starz they would never tolerate from, say, Britney Spears: infidelity.

"We're free agents -- we can work for whoever we want," says Lee. "The industry as a whole isn't making as much money as they used to, so they're running towards people who are actually selling records in this climate now. Sham and I happen to be an entity who are succeeding very well."

That's $30,000 to $70,000 per track to be precise, according to Lee. (Kevin Hall, the Starz' publisher, backs up that assertion.) Of course, it depends. "With somebody who's destined to sell millions of records -- say, Nelly (we're talking to his management right now) -- we wouldn't charge as much for tracks because we can make all our money back on publishing," Lee asserts. "You see most of your money after the fact when it's a multiplatinum seller."

In other words, it's a blinged-if-you-do, blinged-if-you-don't situation.

Hall says it's the Starz' talent for non-sampled, organic beats that has the industry clamoring for more.

"The Trak Starz are unique in that they make the hip-hop a little more musical. What stood out for me with 'Holidae In' was that the track could have easily had a sample but they chose to use a violin. 'One Call Away' could have easily been a sample. They chose to use a guitar player.

"I think they're on the same level as the Neptunes," Hall goes on, speculating that in a year's time they could be as overexposed as Chad Hugo and Pharrell Williams. "They're totally ahead of the trends."

Daugherty and Lee claim "Hollywood ages" of 24 and 28, respectively. Lee's high school, however, says he graduated in 1990 -- likely putting him closer to 31 or 32. Daugherty's high school can't say when he finished up, but the fact that he clues you in that he's fudging probably adds a year or more. They're both just as reticent about discussing their kids -- Lee fathered a son with a woman he's not married to, and Daugherty has two daughters by two different moms, neither of whom is his wife -- other than to say they maintain good relationships with them.

While the girthy Daugherty sports gold-plated front teeth, Lee is smaller and more understated. As understated, anyhow, as someone who sports tens of thousands of dollars' worth of jewelry can be. He grew up "upper-middle class" in University City, attending St. Louis Country Day, where he played electric bass in a band called Room 2 with some friends. The group, which performed at school functions, mixed elements of jazz, funk and rock, heavily influenced by Prince, Led Zeppelin and jazz-fusion drummer Billy Cobham.

"Al was very focused on recording and experimenting," recalls David Kodner, who played drums in the band and now owns art galleries in Clayton and Ladue. "We would basically stay up all night, all weekend -- writing songs, writing tunes and laying down tracks. Al was constantly working on new tunes, different compositions, different layers of sound and melody lines and chorus lines."

After high school Lee ventured west to study music business at the University of Denver but dropped out after two years. He enrolled briefly at Webster University but quit again, opting to directly pursue his musical interests. He started his own production company, scored music for some MTV shows and played with the local group Reggae at Will, then later with funk cover band Dr. Zhivegas.

Daugherty says he spent two years at Hazelwood Central in north county; a check with the school indicates that he was there only one semester, in the fall of 1992. He says he transferred to Gateway High in the city. The school was unable to provide information about his attendance.

In any case, friends say he spent much of his time in school rhyming and tapping beats on his desk. A few years later he joined a rap group called Out of Order that included close friend Jay Hanna.

"Everybody else was either working or doing something they wasn't supposed to be doing," Hanna remembers. "We made music in Sham's parents' back room, using his dad's four-track recorder."

Under the influence of Big Daddy Kane, NWA and the Boogiemonsters, the group made tapes of their music and tried to market themselves. "It seemed like it was a lot harder than the stuff we do now -- a lot more street," Hanna says. Seeking production help, Daugherty met Lee in 2000, through a mutual acquaintance.

Lee agreed to do some production work for Out of Order. Era of Triplossis, the group's 2001 debut, was fairly successful. "World's fastest rapper" and current Top 40 darling Twista showed up on their "Work Som'n Twurk Som'n" single, which cracked the Top 25 on Billboard's rap chart. But by then Daugherty and Lee had formed a bond. They decided to focus on producing and put Out of Order on hiatus. Their work with local crunk group Da Hol' 9 put them on the map. Then came Chingy.

Neither can remember the specific occasion when they met Chingy, insisting they simply "grew up together" -- a testament to the tight-knit nature of the St. Louis rap community in the '90s. At any rate, they came together professionally around March 2001, after the management company T-Love approached them about working with Chingy's group 3 Strikes.

T-Love didn't follow through, and 3 Strikes disbanded. But the Starz stuck with Chingy, and the three set to finding the Jackpot in Lee's $600-a-month lowrise studio/ apartment at Delmar and I-170. It was a cramped affair, especially after Chingy and Daugherty moved in.

"Chingy was on a futon, I was sleeping on the floor underneath the equipment in the studio and Zo was sleeping on his twin bed," recalls Daugherty, who says their waking hours were difficult as well: "The guy who stayed on top of us used to make us cut the music down -- he'd bang on the floor."

The trio worked late night after late night on the album, Lee bringing home the bacon from his gigs with Dr. Zhivegas. While he toured to places such as Springfield and Kansas City, Daugherty and Chingy kept the records spinning.

"We cut over 40 songs in two months," Daugherty remembers. That batch of material included nearly everything that ended up on the album's final version. Chingy had written "Right Thurr" years earlier, but he and Daugherty came up with the hook for "Holidae In" together.

"That's life imitating art," Lee says. "We used to have hotel parties just like the one in the song. Since we lived in the apartment, we would go chill at hotels. Courtyard Marriott was our favorite, because they had whirlpools in the room."

They shopped the album around, finding an enthusiastic ear in Chaka Zulu, an executive at Ludacris' fledgling label, Disturbing tha Peace. DTP signed on, and before long Chingy's grandmother's house and the North Broadway nightclub The Spot were serving as background for the "Right Thurr" video. The single dropped in the summer of 2003 and immediately took over in clubs and on radio.

Starz publisher Kevin Hall blames the outbreak of the Chingy epidemic on one thing: St. Louis slang.

"New artists have to come out with a gimmick first, just to get people to pay attention to them," says Hall "'Right Thurr' was a gimmick. The slang, the drawl on the Southern accent -- it was a gimmicky record."

Though Nelly had introduced the St. Louis vernacular to the mainstream, Chingy based the entire single on it, drawing out the urr in a way that made the nation go Lou-ny. "Right Thurr" went to No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100, followed by a No. 3 showing for "Holidae In" and another No. 2 for "One Call Away." Jackpot is certified double platinum.

"Chingy showed the world that Nelly wasn't a fluke," Lee says. "He officially broke down the door for St. Louis. Despite Nelly, the doors weren't quite open. Now labels are more excited [about St. Louis], more convinced they can win with someone like J-Kwon. It's a great day for St. Louis producers."

For the current state of St. Louis exposure, Lee also credits Basement Beats, who have worked with Nelly, and the Trackboyz, producers of J-Kwon's nouveau hit "Tipsy."

But he's higher on the Starz. "Basement Beats produced Nelly's hits, but they didn't sign him. They were assigned to him. Not to brag, but our first time at bat we broke a national artist. And some people try for years."

The Starz' success in this regard was a precursor for the Trackboyz' success with J-Kwon, who had run away from home at thirteen and moved in with them in advance of making his recently released album, Hood Hop.

Lee says locals have attempted to play up rumors of a beef between the the Starz and Trackboyz (particularly over the similarity of their names), but he's quick to quash the gossip. "We all have different sounds, and it does nothing but help all of us out that so many of us are succeeding," he says. "People try to play up rumors of beefs in St. Louis. But believe me, if you get five young millionaires in a room together, I'm happy."

"They're the best producers right now," Chingy has said of the Starz. "They're steaming hot and they've got a different sound. It's an edgy, rough, street-calligraphy sound."

You'll know you've arrived at the Trak Starz' Lafayette Square studios if you see a pair of H2s in the parking lot. (Lee's is black, Daugherty's pewter metallic.) The $1,500-a-month space, which boasts well-groomed red brick and a quiet atmosphere, does double duty as a crash pad for Lee while his Lake St. Louis dream house is under construction.

The Starz seem most comfortable when they're in the studio, where they can work incommunicado. Before going in, Daugherty records an outgoing message on his cell phone warning that he'll be hard to reach. But in reality, the pair is nearly always hard to reach. Their phones ring constantly -- so much that Daugherty often will only take a call when its announced by a preprogrammed ring alerting him that it's someone he doesn't want to miss.

On this late-winter day, Sony executive Selim Bouab is visiting from New York to oversee the Starz' work on a single for the rapper Baby D. Bouab will stay here, he says, "until they give me a hit record."

"Which will be 45 minutes, tops," Lee deadpans. "Mixed, everything. Ready to roll."

Surrounded by keyboards, computers and drum machines, Lee and Daugherty are engaged in the least cerebral, most challenging and most important element of what they do: finding the hook. Daugherty, whose arms are lined with tattoos including a picture of Jesus and a tribute to his faith in Arabic script, is hammering out the slight variations on a drum machine, and Lee is commenting on the aesthetic quality of a few bars from a sample of the Three's Company theme that plays over and over and over. Other than that, their specific roles in the process seem fairly undefined.

"He pays the ho's, and he smacks 'em," Bouab quips, pointing first at Lee and then at Daugherty.

But really, says Lee, "It's pretty much like a gumbo stew. I have more of a musician's background -- I play guitar, keyboards, drums and bass -- and Sham's more from a hip-hop background."

"One day he may drum-program, one day I might do that," adds Daugherty. "He might play the keyboards, I might play the keyboards. We just swap roles, we can choose on that day."

The Trak Starz aim to form their own record label and stock its roster with St. Louis acts. One group they're working with is STL -- pronounced "S-T-L" -- an angel-faced trio with MTV in their eyes. Unlike the Starz' service-for-hire arrangement with established acts, STL is their pet project, the New Kids on the Block to their Maurice Starr. Having been assembled by Lee's sister Lisa Lee and a vocal producer, seventeen-year-old Whitney Cook, eighteen-year-old Aris Poole and nineteen-year-old Darra Cunningham have never performed live together, much less shot a video. But they've already got their images worked out.

"I want people to see me as cool -- sporty but sexy at the same time," Cunningham says.

"I want people to say, 'They can sing, and dance.' But also: 'They're hot,'" says Cook.

The Starz have them pegged as the world's first successful female crunk group, the next in a long line of assembled pop successes that dates back farther than the Partridge Family. "All the labels are interested," Lisa Lee asserts.

On the other side of the pop-music spectrum -- and from the other side of the world -- comes reggae/dancehall singer Kanjia Kroma, who immigrated to the United States from Sierra Leone in 1997. He moved with his family to Ames, Iowa, where his dad took a job as a professor. Six months later he met former Out of Order manager Demetrius Bledsoe. Now Kanjia is in St. Louis, Bledsoe is his manager, and the Trak Starz have high hopes. They've spent a good deal of time styling his roots-based dancehall sounds into something Top-40 palatable. Bledsoe says Twista will appear on one of his singles. Echoing Lisa Lee's STL claim, he says the major labels are hot for Kroma.

"In the music business you always get, 'You would be good, but you need to have the right connections,'" says Kroma, who performs simply under the name Kanjia. "My chances are a lot better now. With the Trak Starz, they've got the reputation of making sure hot acts come out right."

It's a reputation well deserved, the reggae artist attests.

"If I have a concept for a song, Zo can get on the keyboard and create it, just based on what I'm telling him. They're trying to capture what I'm bringing out, but they bring a different sound to the table -- more lively, more pulse."

"We want to do exactly what we did with Chingy -- to be able to locate regional, local talent, and pipeline that talent to the industry and showcase what's going on here," Lee passionately filibusters. "Major labels tend to follow trends, and very few of them even know what's good and what's not good. It's guys like Sham and I -- and other producers here -- who can go to clubs and hear what's actually good. Guys [in Los Angeles] sit in offices and don't know what's really good. They might sign somebody who's a friend of theirs, as opposed to somebody who actually deserves to be heard."

STL and Kanjia probably won't release their debuts until next year, but you may be able to hear them sooner on a compilation album the Starz have planned, tentatively scheduled for this summer. Under the moniker Trak Starz Present... , the album will feature local and national talent. While they're at it, the Starz are working on an album of their own, featuring Lee and Daugherty taking turns on the mic. Out of Order is also slated to weigh in with a comeback album, in an effort to keep the focus as much on the Starz themselves as the artists they're working with.

"The more visible you become, the more power you have," Lee explains, noting that the music industry has traditionally resisted putting a face on producers.

"It's no secret that they try to shut you out," Daugherty adds. He cites Dr. Dre, Quincy Jones and the Neptunes as inspirations who weren't content to remain behind the scenes.

But anonymity seems to be the last thing the Starz have to worry about. In addition to Chingy's "One Call Away" video, their mugs graced recent issues of hip-hop magazines The Source and XXL. And now, they say, they're negotiating a reality series for VH1 in which they'll take a passé rap star of yesteryear and turn him into a viable market force. The show, titled Remaking the Band, has tentatively slotted none other than Robert Van Winkle, a.k.a. Vanilla Ice, for the makeover. (VH1 spokeswoman Tracy McGraw confirms that the pilot is in development.)

And although CBS won't confirm it, the Starz say they also plan to drop in for an episode or two on a new reality show on that network that will plant Ludacris in a house in England to record his new album amid stuffy servants speaking in proper parlance.

Imagine the culture clash, yo.

"Let's take this shit to his mama house!" a David Banner CD screams in the background as Daugherty relaxes on his Beverly Hills hotel bed.

Back in LA, the Starz have learned that their meeting with Interscope Records president Jimmy Iovine has been pushed back. (They'll see him the next day. "He was in this big office, sitting on a couch with a little pillow with his name stitched in it," Daugherty will say. "He kind of reminded me of a Mafia figure. He had different people from the office stepping in and out, checking in on him. To see him you have to get past all these security guards, like this big fortress." Iovine did not return phone and e-mail requests for an interview for this story.)

With a few hours to kill before the next scheduled meeting -- with Universal -- they're chillin' at Le Meridien. Lee has his own room, while Daugherty is sharing his posh setup with the Starz' "writing team," Jay Hanna and Tony Roberts. They're ostensibly here to help write lyrics for whatever artist the Starz happen to be working with, but Hanna's and Roberts' presence doesn't always appear to be entirely imperative. But Daugherty clearly likes having them around, and Hanna doesn't mind sleeping on the room's loveseat. "I was in the service," the latter explains. "I can handle anything."

Daugherty, though, is feeling less adaptable. Between complaints about the slow room service and the absence of MTV on cable, he makes it clear he's unimpressed with the digs. The Starz usually stay at Le Montrose in West Hollywood, he says, but that's impossible for this late-February jaunt -- they're all booked up for the Oscars.

But he perks up when he describes his new north-county pad. "My first dream house -- real spacious, real futuristic," he says. When it's completed, he says, the space will boast a movie theater with a dozen seats, a pool table, a water fountain and -- like Lee's new house in Lake St. Louis -- a recording studio.

Daugherty breaks off to take a call from his dad, who's worried about the price of a truck his mom wants to buy. "It's $22,000 -- get the damn truck!" Daugherty advises. Then later: "We've got plenty of money coming in, too much money. $35,000 for one beat tomorrow."

After hanging up, he makes a call to order a brush guard for his Hummer.

He's "just real tight with my money," Daugherty explains -- clearly referring more to whom he lets handle it than how he spends it. "I have an accountant, and then just my mom and myself, so other people don't lord over it."

He switches music, to the remixed, unedited version of "Splash Waterfalls." A lusty female voice begs Ludacris to Fuck...me. Room service finally arrives: soup, potatoes, a can of Welch's strawberry soda. While Daugherty chows, Hanna philosophizes about how crazy LA girls are.

"One time a girl here asked if I had any coke," he recounts. "I went to the fridge because I thought she wanted a soda. I brought it back and she said, 'Thanks anyway.'"

"It's serious business out here," seconds Daugherty, who, like Lee, is unmarried. "In St. Louis they're just girls, not big Hollywood actresses."

"Girls out here ignore you unless you're driving a Benz and shit," Roberts adds.

At home things are much less complicated, Daugherty says. "I had girls before, but now it's a whole 'nother level of easiness." Having uncharacteristically slipped into playa mode, he describes how he casts off girls who don't interest him: "I learned how to fast-talk. When people call, I tell 'em I'm in a meeting, that I'll call 'em back."

Finally, well after two, it's time for the day to get started. Lee meets the group outside and hands the valet the slip for the Sequoia. They stare out at the blooming trees lining La Cienega Boulevard, drizzle and smog obscuring Beverly Hills' famous gild. The Starz seem unimpressed with what California has to offer -- by all accounts they didn't leave their hotel rooms last night.

"Me, Zo and Chingy all have experience knowing what that lifestyle's like," Daugherty says of the stereotypical bitches-and-blunts image. "But it's a bunch of hype, and it's overrated to me when somebody gets caught up in the 'big bad superstar, on top of the world' type of attitude. Me, Chingy and Zo are real humble -- we don't ever feel like we've 'made it.' We're always pressing for the next day."

"We could have come to California with bottles of Hennessy and women running around, but we're about business," Lee insists. "A lot of people don't know this, but the music industry is really about 80 percent business and 20 percent entertainment and having fun. If you're not handling your business, that's the beginning of the end for me."

The valet arrives with the Sequoia and off the Starz go. Handling their business.