TESSA WEINBERG/ MISSOURI INDEPENDENT

The Missouri Department of Social Services' Children's Division is dangerously understaffed with high turnover.

This story originally appeared in the Missouri Independent.

Eighty open cases of child abuse and neglect sat on Matt Cordova’s desk in 2017 during the height of the “hole I found myself buried in,” he remembers.

Twenty open cases would have been a lot to handle; 80 was impossible.

An investigator at Missouri’s child welfare department for two years, Cordova was tasked with following up on reports made to the child abuse and neglect hotline. Investigators make home visits to any child allegedly abused or neglected to assure their safety within a set timeframe.

For Cordova, who worked in a rural circuit spanning four counties, that could mean hours on the road each day, sometimes driving hundreds of miles.

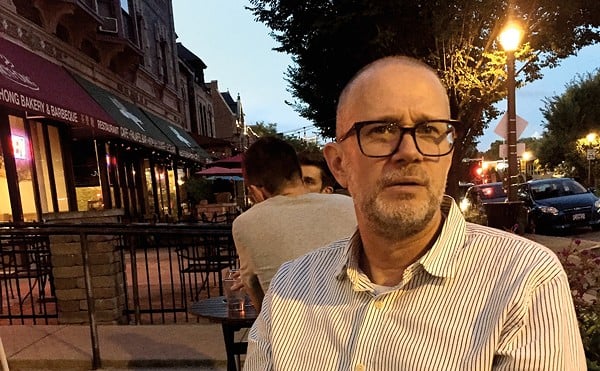

COURTESY PHOTO

Matt Cordova worked at Children’s Division from 2016 to 2018 as a child abuse and neglect investigator.

He was on-call for one week each month and could be summoned at any point, day or night, to investigate a hotline tip. The most urgent calls required a three-hour response time, often leaving him scrambling for childcare.

“You could spend your entire weekend or all night going out and looking for kids,” he said.

He was paid $35,000 a year.

For Cordova, like many of his fellow Children’s Division colleagues, the job became too much. He left in 2018.

“It’s so easy to get burnt out,” he said, “so easy to get overwhelmed and you start to lose your grasp on that passion to help children.

“I don’t think they see the correlation between burnout and treatment of children.”

Since Cordova left, the situation in Missouri’s Children’s Division has only gotten worse.

The Independent over the last two months has spoken with current and former employees of Missouri’s Children’s Division who, like Cordova, experienced the effects of high turnover rates and low morale — as well as with advocates, researchers and attorneys concerned about the system’s far-reaching effect on children and families.

For the agency tasked with handling child abuse and neglect investigations, and overseeing the state’s foster care system, the ramifications can be severe.

Foster children are missing visits with their parents and languishing in care of the state for longer than they should be, according to several of those interviewed. Some foster children’s cases outlast their caseworkers’ tenure at Children’s Division and are handed off to a new caseworker, which lowers children’s chances of reunifying with their families.

On the investigation side, some worry with such high caseloads and the loss of veteran workers, mistakes could be made which, at either extreme — needlessly removing a child, or overlooking signs of abuse and neglect — would be life altering for the child and family. At the margins, the investigators don’t have the time to connect with lower-risk families in ways that might prevent future allegations of abuse or neglect.

Children’s Division Director Darrell Missey, who was appointed to the job in January, has been candid about the issues facing his division and has committed to solving them.

Last month he acknowledged the staffing issues as a “crisis.”

“We need to work to stabilize the [work]force.” he said. “Then, we’ve got to get enough people so that they can actually have a number of cases they can manage. And we have to work on prevention.” Missey said the system has long trended toward the “reactive” over “proactive,” and is “driven by our fear of what might happen later, [which] results in a lot of kids in foster care.” Now, the state is faced with a dual crisis: Too few staff to oversee far too many children.

‘Families get put on the back burner’

Missouri’s Department of Social Services (DSS), which oversees Children’s Division, has long faced staffing issues, budget cuts and high turnover. But in recent years, the challenges have been especially severe.

DSS, which includes three other program divisions plus Children’s Division, had an overall staff turnover rate of 35 percent last fiscal year, ranking second among state agencies of its size after only the Department of Mental Health.

In the Children’s Division, it’s even worse. Among frontline Children’s Division staff — including child abuse and neglect investigators and foster care case managers — the turnover rate last year was 55 percent, according to data provided by DSS. That means more than half of the frontline staff working at Children’s Division across the state at the start of the last fiscal year had left by the end of the year.

Turnover is highest in the metro areas. In Kansas City earlier this year, the rate was 88 percent.

The agency has struggled to hire in pace with the departures. There were 228 full-time equivalent front-line vacancies in Children’s Division staff as of Aug. 31, according to DSS’s spokesperson. Turnover leads to higher workloads for those who remain, which begets more turnover.

“Families get put on the back burner,” said Mike Herrin, a Kansas City child welfare attorney. “We sometimes have months where kids don’t get to see their parents.”

Staff turnover and high caseloads are linked to worse outcomes for children in foster care, in terms of their likelihood to reach reunification or adoption, studies have found. Once a case was handed off to a new caseworker, a Wisconsin-based study found, the chances of a child reunifying with their families within a year dropped from roughly 75 percent to 18 percent.

Staffing challenges have been compounded by Missouri’s historically high rate of children in foster care.

In terms of its rate of removing children from their homes, “Missouri has been an outlier for decades,” said Richard Wexler, executive director of the nonprofit National Coalition for Child Protective Reform.

Some, like Wexler, argue the deeper issue is that Missouri needs to shift funding away from bringing so many kids into foster care, which is often traumatic for children, and toward funding preventative measures which would also reduce the need for so many staff to manage them.

When the population of children in poverty is taken into consideration, Missouri ranks 13th for the rate of removing children from their homes, the National Coalition for Child Protective Reform found. The state removes children at a rate 50 percent higher than average, NCCPR found.

There are currently almost 14,000 children in foster care, an umbrella term which refers to several ways the state can serve as the stand-in parent for the child. States generally prioritize placing children in temporary care with relatives — half the kids in Missouri’s foster care system are in placements with relatives. Roughly one third are in traditional foster families with strangers, and under one tenth are in group facilities.

DSS does dedicate some resources to preventative work, though Missey and others argue it’s far from enough.

Family Centered Service workers are called in when the state has concerns that don’t rise to the level of removing the child. Those workers are also stretched thin, though: Cordova, the former investigator who once had 80 cases, remembers there were only one or two Family Centered Services workers covering his four counties.

The number of open Family Centered Service cases has dropped over the last five years, according to DSS’s annual reports. Other DSS services to prevent families from being separated, like the privately-contracted Intensive In-Home Services, have fewer openings than demand, resulting in children each year going directly into foster care who can’t get the services. Last year, 19 children entered foster care who were denied Intensive In-Home Services due to availability.

Once children are in foster care, the state has consistently failed to meet the federal timeliness standard for placing children in a permanent home, through reunification or adoption. The national standard is 42.7 percent of children finding a permanent home within a year of entering custody. In Missouri, the rate last year was just over 30 percent.