Republicans all the way up to the president unloaded on St. Louis Circuit Attorney Kim Gardner this summer as she investigated and then charged a wealthy pair of married lawyers for pulling guns on protesters.

"Kim Gardner owes every single family who has had a loved one murdered an explanation on why she has acted on the McCloskey case instead of theirs," Missouri Governor Mike Parson tweeted.

"This is part of a troubling pattern of politically motivated prosecutorial decisions by the St. Louis Circuit Attorney ...," wrote U.S. Senator Josh Hawley in a letter calling on U.S. Attorney William Barr to investigate Gardner.

"It's a disgrace," President Trump told a conservative news website.

Normally, the filing of a low-level felony would not merit mention in St. Louis, much less nationally. But Mark and Patricia McCloskey were already on their way to Joe the Plumber status, joining the pantheon of randos plucked from obscurity for the latest campaign narrative.

The couple appeared on Monday in a video for the Republican National Convention, warning that anyone living in "quiet neighborhoods" was in peril from "radicals" who wished to "abolish the suburbs." (Note: The McCloskeys don't live in the suburbs.)

"Not a single person in the out-of-control mob you saw at our house was charged with a crime, but you know who was?" Mark askded in the video. "We were. They've actually charged us with felonies for daring to defend our home."

On June 28, the husband and wife were dining on the east patio of their fortress-like mansion when protesters started to march past on their way to Mayor Lyda Krewson's home. In the McCloskeys' telling, they were faced with a violent "horde" and had little choice but to arm themselves, lest they be murdered with their dog and their opulent house set ablaze. Their account conflicted with a livestream video that showed no signs that marchers intended to harm the couple or even noticed them until Mark, carrying an AR-15 rifle, began shouting, "Get the hell out of my neighborhood!" Patrica shuffled onto the lawn, panning across the crowd with a pistol as demonstrators shouted at them to put away their guns. After about ten minutes, the crowd moved on. But video and photos of the rich white couple brandishing guns at a diverse group of protesters went viral.

For the left, the incensed, armed McCloskeys couldn't have been more on the nose as mascots of white privilege and rage. But for conservatives furious about nationwide protests after George Floyd was killed by Minneapolis police, the McCloskeys became instant folk heroes. And when Gardner stepped into the morality play the next day by announcing she intended to investigate the McCloskeys, Republican politicians eager to talk about anything other than the coronavirus had their villain.

Kim Gardner has repeatedly taken on explosive cases since taking over in 2017 as St. Louis' top prosecutor.

She inherited the case against Jason Stockley, a white ex-St. Louis cop who was ultimately acquitted that September of first-degree murder in the point-blank shooting of a Black 24-year-old named Anthony Lamar Smith. Prosecutors' theory was that Stockley planted a gun on Smith after killing him, but Judge Timothy Wilson rejected that argument. Wilson's verdict, which included a written explanation that an "urban heroin dealer not in possession of a firearm would be an anomaly," sparked the most intense protests in St. Louis since Ferguson. However, aside from pissing off the St. Louis Police Officers Association, Gardner's role was overshadowed by the clash between activists and police.

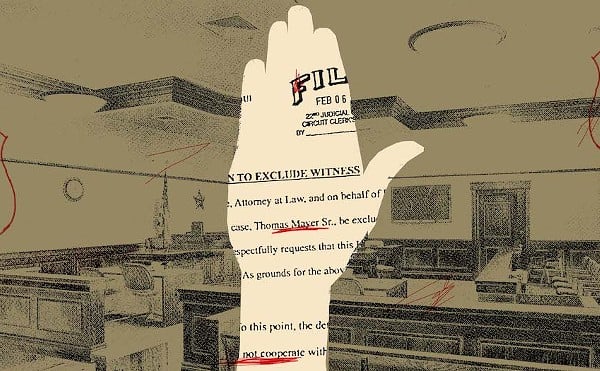

The situation would be different in February 2018, five months after the Stockley verdict, when Gardner dropped a bombshell, filing a felony invasion-of-privacy charge against then-Missouri Governor Eric Greitens for allegedly taking a photo of a mistress while she was partially nude and then threatening to release it if she revealed their affair. A second charge of computer tampering alleged the Republican governor illegally used a donor list of a nonprofit he founded for his political campaign.

It was a bruising case — for Greitens, who resigned in March 2019 as part of a deal to drop the tampering charge, and Gardner, who found herself playing defense against accusations of misconduct lodged by the governor's powerful attorneys.

The Greitens prosecution took criticism of Gardner to a new level, introducing her to a broader audience of right-wing antagonists across the country. In St. Louis, she continued to clash with the police union, showing a willingness to charge cops in shootings that outstripped her predecessors. In August 2018, word leaked out to the public that she kept an "exclusion list" of more than two dozen city police officers whom prosecutors didn't trust to present cases or testify at trial. That kicked off a new battle with the police union and its mouthpiece, Jeff Roorda. In a radio interview in September 2019, Roorda called the prosecutor a "menace to society" and said she should be removed by "force or by choice."

As far as the union was concerned, Gardner was a leader in a war on police. As she prosecuted cops — or refused to accept cases from officers on the exclusion list — crime had surged out of control, they claimed.

It isn't just the police union that has pushed the narrative of a city overrun by criminals coddled by a soft-on-crime prosecutor. Conservatives in Missouri politics, who've long made a sport of scaring their constituents with nightmare tales of St. Louis violence, keyed in on Gardner as a foremost practitioner of catch-and-release law enforcement.

When the McCloskey case hit, they blasted the charges as an assault on the 2nd Amendment and an example of wildly misplaced priorities at a time when St. Louis homicide totals were rising.

"It's created a real problem on the streets," state Attorney General Eric Schmitt told former NRA spokeswoman Dana Loesch on her show in July while discussing Gardner's record. "It has emboldened criminals. They think they can get away with literally murder."

There has been a lot of murder this year in St. Louis.

As of Monday, 172 had been killed, compared to 128 at this time in 2019. The city is on pace for its deadliest twelve months since the bloody days of the early 1990s.

To make matters worse, according to Parson and Schmitt, there is a "backlog" of murder cases going unprosecuted by Gardner. In an August 10 news release, the governor cited police statistics showing charges had been issued in just 33 of what was then 161 homicides in the city. But the implication that Gardner was sitting on a backlog of 128 murders is, at best, grossly misleading. That's because it leaves out a key piece of the equation: arrests. As of August 14, police officers had arrested 44 people in homicide cases and charges had been issued by the circuit attorney in 34 cases, according to a department spokeswoman. The St. Louis police force's clearance rate for homicides has hovered between 30 and 40 percent in recent years, well below the national average of 62 percent in 2018, the most recent year available. Explained another way, prosecutors can't charge murder cases they never see.

It is true that Gardner turns away more homicide cases than her predecessors, and her prosecutors lose more of the felony cases they take to trial. So far this year, Gardner has sent back ten homicide cases, according to police statistics. Her office's trial conviction rate for felonies, which includes more than homicides, is slightly better than 50 percent. By comparison, Jennifer Joyce refused to issue charges in just one murder case presented by police during her final two years as circuit attorney, and the office's felony conviction rate at trial was better than 70 percent. (Gardner points out that trials account for a tiny fraction of the volume of cases, and her overall felony conviction rate, which includes pleas, is 97 percent.) What that says about differing standards for issuing cases — or the working relationship between police and prosecutors — is up for debate, but it doesn't show a backlog of cases in the circuit attorney's office.

That hasn't stopped Parson and other Republicans from making it a talking point as they head toward an election in November. In July, the governor called a special legislative session to debate a series of measures, including the elimination of residency rules for St. Louis cops and creating an expanded avenue to try kids as young as twelve as adults. Less than a week after Gardner rolled to an easy victory in the Democratic primary, all but guaranteeing she'll win reelection in November, Parson moved to add another piece — new powers of the attorney general to take over St. Louis murder cases under certain circumstances.

Under the proposal, the attorney general could pick up murder cases 90 days after police present them if the circuit attorney has yet to issue charges and the chief law enforcement officer requests that the attorney general intervene.

"This proposal is not about taking away authority," Parson said in a news release. "It is about fighting violent crime, achieving justice for victims and making our communities safer."

It would, however, provide for a scenario where the attorney general could prosecute cases that Gardner's prosecutors have rejected as too weak or are still waiting on additional evidence for. She says the key to building cases is building trust with the community, so that witnesses and victims feel comfortable working with investigators. Inserting the attorney general won't speed up the process, she says.

"It takes time, and there is no time limit," Gardner says. "This is not a TV show."

The governor's proposal assumes that the bottleneck in murder cases lies in the circuit attorney's office and violent crime is up as a result. Both are questionable conclusions.

Criminologist Richard Rosenfeld, a professor at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, has studied the surge in violent crime during the pandemic — not just in St. Louis, but across 27 cities. He doubts that anything Gardner is or isn't doing is behind the increase.

"I think it's unlikely," he says. "That might be the case if we were only seeing the rise in St. Louis, but we're seeing the rise in many other cities across the country."

Across the twenty cities where homicide data was available, homicides increased 37 percent in late May and June, and aggravated assaults increased 35 percent across seventeen cities, according to a recent report authored by Rosenfeld and UMSL graduate student Ernesto Lopez Jr.

Even accounting for the usual uptick in violence that tends to come with summer, the increase is significant. Rosenfeld notes that it comes during a time of upheaval, not just from the pandemic but widespread protests that followed George Floyd's death.

Something else has happened during the pandemic in St. Louis: A lot of the face-to-face policing stopped. Car stops, building checks and other activities that police categorize as "self-initiated" dropped sharply. Traffic violations alone fell by more than 90 percent as police changed their strategies in hopes of slowing the spread of COVID-19. In an interview with the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, police Captain Renee Kriesmann said officers were temporarily instructed to not pull over vehicles or stop pedestrians unless a serious crime was being committed. The paper noted that in the police department's 4th District, which includes downtown, police reported no traffic violations in July, compared to 265 during the same four weeks in 2019.

Police have since resumed self-initiated activity, but it's too early to say whether that will make a difference on August's numbers. In July, the city recorded 55 homicides, more than double the 22 killings in July 2019.

In an interview, Rosenfeld says there could be other factors at play. It's possible that populations that have typically had fraught relations with law enforcement are even less likely to call them or work with them as police protests continue across the country. Time will provide more clarity about the cause of the increased number of killings, but Rosenfeld and Lopez write that controlling COVID-19 is a good place to start:

"In our view, subduing the COVID-19 pandemic is a necessary condition for halting the rise in violence. In addition, both the rise in violence and social unrest are likely to persist unless effective violence-reduction strategies are coupled with needed reforms to policing."

After Kim Gardner charged the McCloskeys, she said she received a flood of racist emails and even death threats. In an interview with the Washington Post, she compared it to the old Ku Klux Klan terror campaigns.

"This is a modern-day night ride, and everybody knows it," she told the newspaper.

Adding Trump's criticism to the fray — Parson said at a news conference in late July that he had to explain to the president that the governor didn't have the authority to remove Gardner from office — further intensified the criticism she'd faced since becoming St. Louis' first Black circuit attorney, she says. She considers it part of powerful politicians at the state and federal level trying to "inject" themselves into the duties of a local prosecutor.

"And you have to ask yourself, 'Why would they do that?'" Gardner says in a phone interview. "Well, I know why. It's a way to cause fear and divisive rhetoric, and to distract from their failed leadership to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic."

Parson spokeswoman Kelli Jones says there is nothing personal or political about his interest in St. Louis crime, and she defended his request to let Attorney General Eric Schmitt start prosecuting some of the city's homicides.

"This proposal is not about taking away authority," Jones says in an email. "It is about fighting violent crime, achieving justice for victims, and making our communities safer. Under the proposal, the Circuit Attorney still has full and fair opportunity to prosecute murders."

Chris Nuelle, a spokesman for Schmitt, also insists there is no political motive behind the attorney general's support for Parson's proposal.

"This is purely about obtaining justice for victims, protecting our communities, and prosecuting violent crime," Nuelle writes in an email. "The Attorney General was born and raised and represented the St. Louis region, and cares very deeply about what happens to the City of St. Louis. Fighting violent crime should not involve personalities or politics."

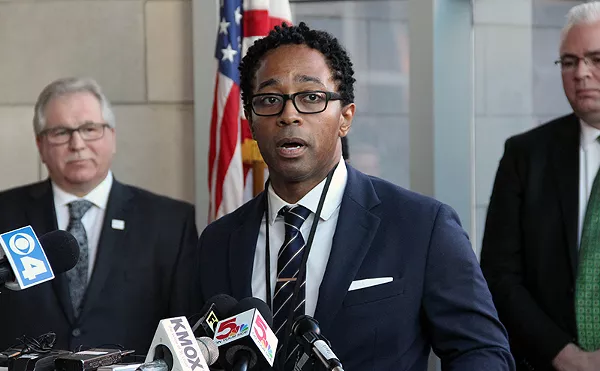

Schmitt stands out among the circuit attorney's critics. After the McCloskeys' showdown with protesters, he hit the conservative talk show circuit, calling her a "rogue prosecutor" with an "abysmal record" on violent crime.

A former state senator, he and Gardner have clashed repeatedly. Schmitt blasted her early in the pandemic when she worked with public defenders to identify dozens of defendants for recommended release from city jails in hopes of heading off an outbreak among inmates and jail staff.

And when four cops were shot and a retired police captain killed during rioting and looting that followed nonviolent police protests in early June, he tweeted a video of a burning car.

"In a stunning development, our office has learned that every single one of the St. Louis looters and rioters arrested were released back onto the streets by local prosecutor Kim Gardner," Schmitt wrote in the tweet, which has been retweeted more than 29,000 times.

It wasn't true. Only a fraction of more than 30 people arrested had even been referred to the circuit attorney at the time of Schmitt's post, and then only on charges of stealing. Police released the rest without applying to prosecutors for charges.

Asked if the attorney general has corrected the tweet, Schmitt's spokesman Nuelle says in an email, "I can't comment on the AG's personal Twitter account or directly on that tweet, but I will say that SLMPD presented cases for prosecution to the CAO, and they refused to prosecute any of them immediately. We're glad that after the Attorney General made comment on this situation, the CAO did finally charge some of those offenders. The CAO also had a policy in place preventing the police from presenting cases for property damage resulting from looting and rioting."

On the day of the tweet, Gardner responded in a video statement.

"I've noticed that the attorney general is tweeting quite a bit about looters and rioters and not about the fact that we have a history of police violence in this city and nation," the prosecutor said. "And that has caused people to take to the streets yet again to demand accountability and change in our criminal justice system. It is clear that he does not care about justice or safety or the needs of this community. He just wants to launch a politically motivated attack against me, even if it means misleading and lying to the public."

The dustup was a precursor to the battles Gardner would fight after the McCloskey arrests: Republican officials claiming she's letting criminals off easy; Gardner firing back they deliberately miss the point.

"We never talk about the governor who was a senator, and an attorney general, who directly caused a lot of the violent crime in the city of St. Louis by gutting our gun laws," she says. "We never talk about how they have a history of not funding education, a history of cutting access to health care as well as social services that we all know could address the root causes that drive individuals to the criminal justice system. But we never report on that. It's, 'Kim Gardner is the cause of crime.'"

We welcome tips and feedback. Email the author at [email protected] or follow on Twitter at @DoyleMurphy.