One year ago this week, three area prosecutors gathered in a briefing room near the St. Louis County courthouse to announce that a 30-year-old cold case had been closed.

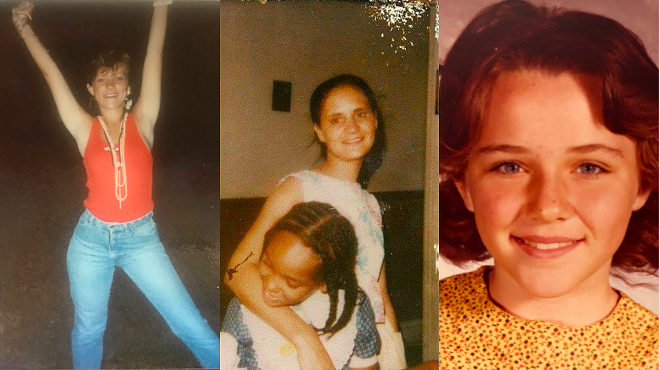

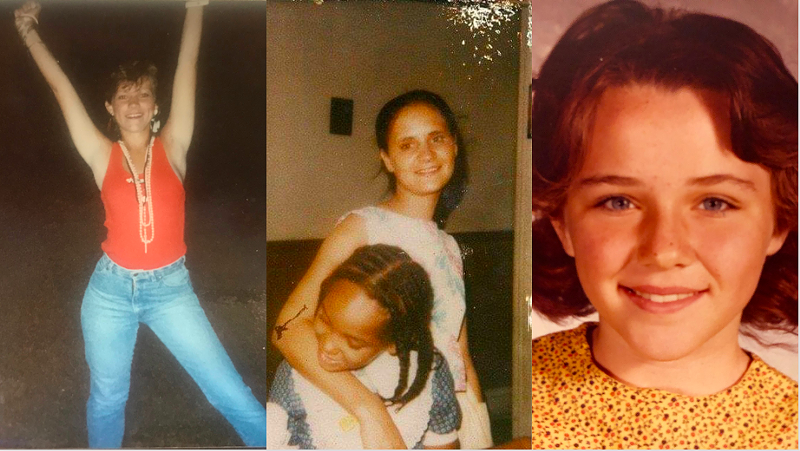

Earlier that day, murder charges had been filed in three different jurisdictions against 73-year-old Gary Muehlberg. Between 1990 and 1991, Muelhberg had abducted five women from south city, killed them in his home in Bel-Ridge, and then abandoned their bodies in conspicuous packages alongside roads and highways throughout the metro area. His victims included Robyn Mihan, Donna Reitmeyer, Brenda Pruitt, Sandy Little and an unknown fifth victim. The four known victims were all mothers. Many of their children, as well as their parents and siblings, were present for the press conference when the charges against Muehlberg were announced.

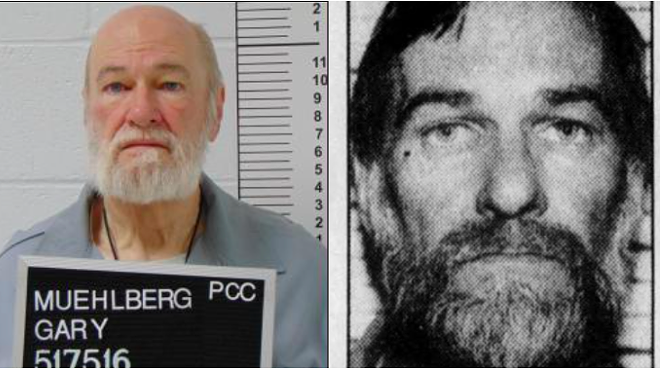

Though the charges were 32 years in the making, the investiagtion's final chapter had begun just three months prior, in June, when O’Fallon Police Detective Jodi Weber made her first trip to Potosi Correctional Center to interview Muehlberg. He'd been incarcerated since 1995 for the murder of a man named Kenneth "Doc" Atchinson, whom Muehlberg killed in order to rob him of his money and a car. Because of the murder conviction, Muehlberg's DNA was in a registry, and in 2022 DNA recovered from four pieces of evidence from the unsolved 1990 and 1991 murders came up as a match to his.

When Weber went to interview Muehlberg in prison that June, she felt confident she had the killer, yet the process of securing guilty verdicts would be much easier if she could get him to confess.

"I knew going in there that I had him dead to rights," Weber says. "There's no denying this. I'm going to show him the lab reports. I'm gonna show him, ‘We got you.’"

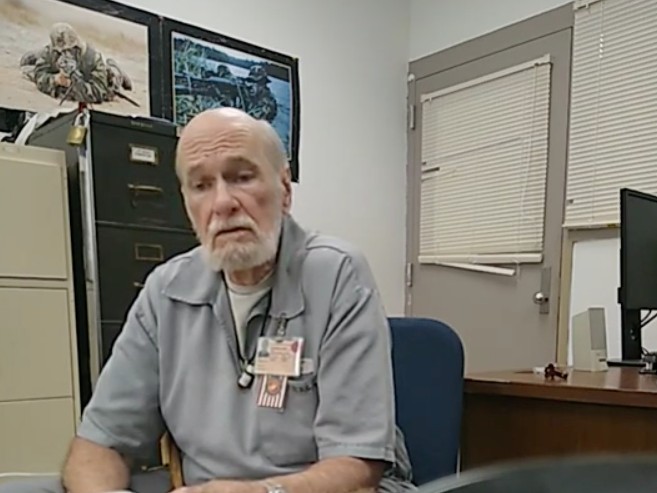

Muehlberg himself says of that first meeting with Weber that he’d been under the impression he was going to the prison's medical unit, but was instead ushered into a room to find Weber and another detective, Mike Harvey, waiting for him.

"I was tired of running. I was relieved to be quite honest," Muehlberg told me later in a phone call. "OK. Which direction do I go? Acceptance and responsibility or denial. Screw the denial."

Yet over the course of approximately nine hours of being interviewed by Weber on four different occasions, Muehlberg engaged in plenty of denial and evasion. He did eventually confess to the five murders, but there is an astounding amount he says he can't remember. Weber can't help but wonder if there isn't more he isn’t saying.

"We really don't know if we know all of what Gary has done," Weber says.

In that first interview, which took place June 30, 2022, Muehlberg shuffled in with the help of a cane, wearing shorts and prison-issue flip-flops, his image the far cry of a man who had once terrorized south city. At the time, Weber only suspected him for three of the murders — of Mihan, Pruitt and Little, women whose deaths had been so similar they had to have been committed by the same man.

A police camera captured Weber introducing herself, saying, "I've waited a long time to talk to you."

"Really?" Muehlberg replied.

"I guess you don't get many visitors?"

Muehlberg shook his head. "No." He added, "Get to the chase. What's going on?"

Weber and Harvey told Muehlberg they were there to talk about a series of homicides, that substantial DNA collected at the crime scenes connected him to the victims.

"You're talking to me like you're accusing me of a homicide," Muehlberg said.

He listened to the detectives for about an hour, denying everything they said. At one point, foreshadowing what will become something of a theme, Muehlberg told the detectives, "I'm not going to cop to something I didn't do or don't remember doing." He eventually said he wanted a lawyer and called an end to the conversation.

"I was really disappointed in the first interview," Weber recalls. "We left there on bad terms."

Muehlberg expressed reservations about confessing to murders because, even though he was already locked up for life for the murder of Atchinson, he worried that prosecutors might seek the death penalty for the murders of the women. Weber was able to get the three prosecutors who would have jurisdiction over Muehberg's crimes to write letters promising not to seek capital punishment. She returned to Potosi in August with those in hand.

Muehlberg was again captured on video taking his time reviewing the letters from the prosecutors. "OK. So now what?" he said.

Things went significantly better for Weber the second time around. However, even when Muehlberg was supposedly confessing, he asked as many questions of the detectives as they asked him.

Weber put a photo of Muehlberg's first known victim, Robyn Mihan, in front of him. Muehlberg responded by asking, “How did she die?”

When discussing how Mihan was found beside a highway between two mattresses, Muehlberg asked, "[The mattresses] were secured together, with a rope or whatever?"

"I was hoping you could tell us," said Harvey.

"Do you remember doing it?" Weber asked, point blank.

"Vaguely."

After a few more minutes of back and forth with the detectives, Muehlberg said of Mihan's murder, "I've been thinking about that. I can't recall the circumstances I met her, but I guess if my DNA and all that stuff ties me to it, I'm good for it. But I don't remember a lot of the details."

Specifics of how he met the women, their last moments, how he took their lives, how he disposed their bodies, and why in some cases he waited months after killing them to do so — on all this, Muehlberg was incredibly vague, with the detectives working with strained patience to pull concrete detail from him.

"I was frustrated," Weber recalls. "We asked him a question and he acted like he didn't know or couldn't remember. I wanted to be like, 'Yes, you do. You remember this! You need to come clean.'"

Weber says she refrained from doing so because Muehlberg had demonstrated in their first interview that if he grew upset with her, he was going to clam up.

"I don't buy the fact that he doesn't remember doing it," Weber says. "He remembers. He just doesn't want us to believe that he's this monster."

Muehberg's inability to recall so many details of his crimes is at stark odds with his sharp memory when it comes to more mundane aspects of the same period of his life. For instance, about the van he drove at the time, he recalled that it was “a late ‘80s Ford conversion van. Factory custom. It had the captain seats and all that good stuff in it.”

A few times during the interviews, Muehlberg claimed he'd "blacked out" the details of his crimes. He frequently told the detectives interviewing him that trying to recall the details is "painful as hell."

Speaking generally, Sandra Langeslag, a professor of psychological sciences at the University of Missouri St. Louis, says that sort of memory repression rarely happens. "The people that study memory know that memory doesn't work like that," she says. "Typically, we remember things that are emotional or traumatic better than a neutral thing."

She says that factors like drug or alcohol use, or a head injury, can cause memory loss. Muehlberg describes himself as a near-teetotaler during the time he committed the crimes. If he has suffered a head injury, it didn't come up in the nine hours of questioning.

Langeslag says that it's very difficult to know for sure if someone is faking memory loss, but it's a "red flag" if a person has a clear recollection of events that weren't criminal but occurred around the same time as the criminal act they claim not to remember. Muehlberg clearly recalling the details of the van he drove in the early 1990s qualifies as a red flag.

Weber says it's more than just Muehlberg's supposedly spotty memory that makes her think there may be more victims. For one, he's lied about it before.

In the second interview she conducted with him, the one in which she handed over the letters from the prosecutors taking the death penalty off the table, Muehlberg only confessed to the three murders that he knew Weber was aware of: the killings of Mihan, Pruitt and Little. Near the end of that interview, she asked Muehlberg if there are any other victims. He said no.

However, after that second interview, Weber got a letter from Muehlberg in which he said he hadn't been completely honest. There were more victims.

Weber and Harvey returned to Potosi for a third interview, this time with Maryland Heights detective Chris McNamara. During a third interview, Muelhberg confessed to killing Donna Reitmeyer as well as a fifth victim whose name he doesn't recall, perhaps never knew, and who remains a Jane Doe.

Given that Muehlberg had suddenly recalled two additional murders, it seems possible that there could be others.

At one point, McNamara directly asked Muelhberg, "How many people do you think you've killed in your lifetime?"

Muehlberg exhaled heavily. "I don't really know how to answer that question. Directly or indirectly?" He mentioned his year of military service, even though he never saw combat.

After a few more beats, he said, "Just those six."

About Muehlberg's response to that question, Weber says, "The comment that he made at that time, it tells me there's more."

This March, Muehlberg did have to speak plainly about his crimes when he pleaded guilty in three separate courtrooms to the five murders. He was allowed to appear via video call at his hearings, which were all about a week apart, sparing him from having to be in the same room as the families of the women he killed. Nonetheless he did have to unambiguously admit his guilt.

"For him to say, 'I did it. I'm responsible,' for those words to come out of his mouth, I think is huge for the victims' families," Weber says of Muehlberg's days in court. "It would be for me at least."

Saundra Kuehnle captured the mix of emotions multiple family members said they felt at the hearings. She appeared in court in Lincoln County for the final one, to hear Muehlberg plead guilty to killing her daughter.

"I prayed the good Lord would let me live long enough for the monster, whoever it was, to be caught and convicted," Saundra said at the time. "Even if they had to bring me in on a gurney, I'd come to court."

However, speaking to Muehlberg directly over video call from the courtroom, she said: "I don’t quite understand, Mr. Muehlberg, how you are not able to be here face to face. The murders weren’t done by Zoom call.”

Now, a year later, in addition to wondering if Muehlberg may have killed more than six people, Weber wonders if he may have had some sort of accomplice.

"I'm not entirely sure there's not somebody else," she says. "Who at least maybe didn't help commit the murders, but maybe helped dispose of the bodies.”

After the murder of Atchison, Muehlberg tried unsuccessfully to coax an accomplice to help him move the body. And in a witness statement from 1990, someone came forward to police saying that they saw two men discarding mattresses on the side of the highway in Lincoln County on the morning that Mihan's body was found there.

In March, when Muelhberg appeared via video call to plead guilty to the murder of Sandy Little in St. Charles County, Little's sister Geneva Valle-Palomino and stepsister Barb Studt were in the courtroom.

After the hearing, Studt said that even though she knows it's macabre, she can't help but wonder about the final moments of her stepsister's life. She wishes that Muehlberg would be more forthcoming.

"What I imagine in my head could be worse than what it was, could not be as bad as what it was," she said. "I do think about it."

Muelhberg called me the day after that hearing in St. Charles.

We had a somewhat awkward back and forth. I asked him if he ever had dreams about the people he killed. "Not that I recall," he said. He talked about his Christian faith, which seemed to have been rekindled while in prison, as well as how he'd recently been offered money for interviews, which he turned down. He said he just wanted to "do the right thing."

I conveyed to Muehlberg the notion that if he really wanted to provide closure to the victims' families, at least some members of them have said they wanted to resolve the uncertainty they have about the circumstances of their loved ones' murders. Speaking of Studt, I said, "She's worried that way she imagines it might be worse than it actually was."

“Not saying one way or the other, but by advice of my counsel, I'm not going to talk in detail about anything until everything is over,” he replied.

At the time, he still had one more court date, the one in Lincoln County. He said afterwards he’d be willing to meet in person, hinting he’d discuss things he never had before. “Maybe someday in the near future after everything is finalized, I might be able to answer some personal questions but, you know, I can't say much on that,” he said.

Muehlberg pleaded guilty in Lincoln County. We spoke a few more times over the phone, but he ultimately never opened up further or agreed to be interviewed in person.

One of the last times he called me from Potosi, he implied that he still hadn't made up his mind about telling the full truth. Though, reading the transcript of the conversation again, now, I think he may have revealed more than he intended.

"If I could remember everything, do I want to be completely honest? Or do I want to sugarcoat it for their sake?" he said, referring to the families of the women he killed. "I'm not saying one way or the other on this, it's just speculation right now."

He went on, "Should I be honest if they suffered and screamed and fought? Or should I, on other hand, for their sake, should I say, rest assured they did not suffer? They did not know what was going on?"

or follow on Twitter at @RyanWKrull.

Subscribe to Riverfront Times newsletters.

Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter | Or sign up for our RSS Feed