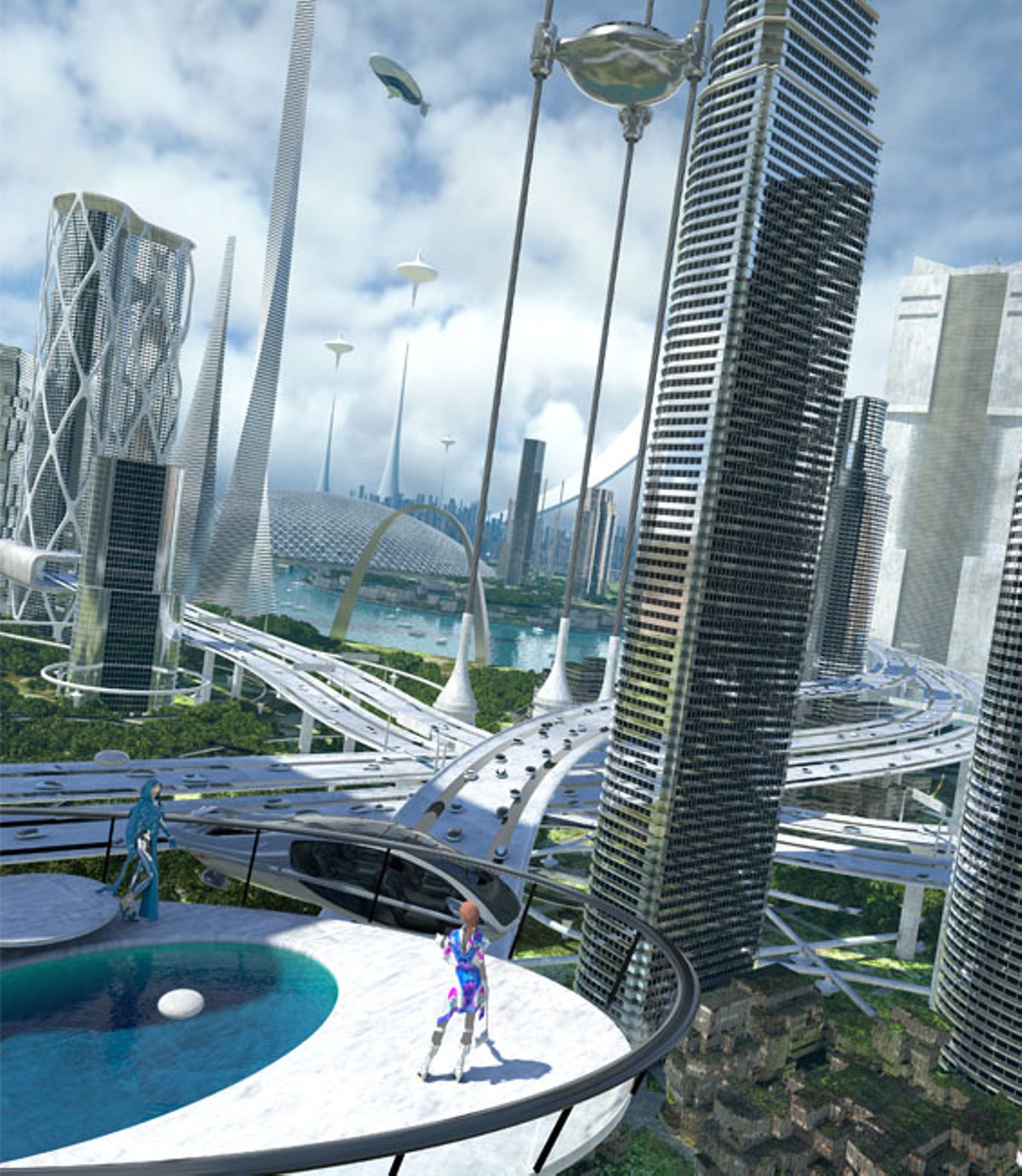

The future of St. Louis — it's the first thing Jody Sowell sees when he enters his office at the Missouri History Museum. Granted, it's just an illustrated poster that hangs behind his desk — a gorgeous, minutely detailed vision of the city. A Forecast, it reads. Looking Up Olive Street, St. Louis, Missouri, in the Year 2010. It was commissioned way back in 1910.

"We often focus on what they got wrong," says Sowell, the director of exhibitions and research with the museum. "Innovation...it never goes as fast as we actually think it will."

On the eve of St. Louis' 250th birthday, it's hard not to regard the predictions in Sowell's poster with some bemusement. In the illustration, a riverfront view opens to a broad city street with bustling pedestrians and buses dwarfed by skyscrapers. Public-transit blimps float to and fro. A futuristic citadel rises over downtown on curved legs of impossible scale. Not everyone who thinks years into the future has the luxury of being so impractical. Take Don Roe, director of the city's Planning & Urban Design Agency. In 1914, Roe's predecessors drew up the first plans to revitalize the city's decrepit riverfront. Today, it's his job to take a measured, calculated approach to planning for the city's long-term future.

"Two-hundred-fifty years ago we settled along the banks of the Mississippi, and looking a hundred years from now, this place can still be a magnate for growth," he says. "Water is going to play a major role in shaping St. Louis and the region and as a whole."

As the city embarks on its 250th year, we here at Riverfront Times decided we wanted to mark the occasion by making some predictions of our own about what St. Louis will look like in 100 years. We called up some of the best local thinkers from the world of business, sustainability, transportation, agriculture and more, and asked what the denizens of the 2114 Gateway City will be building, eating, drinking and growing a century from now. They were kind enough to indulge us.

We also admit that, like the illustrator of A Forecast, we're choosing a decidedly optimistic vision of the future — no zombie apocalypse, population collapse or nuclear holocausts for us. And if that makes us a bunch of cockeyed optimists, so be it. Birthdays are for making wishes.

—Danny Wicentowski

While this winter has been particularly bitter, warmer climes really are coming to St. Louis. Adam Smith, a postdoctoral fellow at the Center for Conservation and Sustainable Development at the Missouri Botanical Garden, says temperatures in St. Louis have been rising steadily over the last 30 years. In another 100, he predicts, the area's average temperature will jump 8 degrees, from a yearly average of 56 degrees to 64 degrees. A typical day in July or August will blister at 100 degrees, with the hottest days clocking in well above that.

"This worst-case scenario assumes that humans do about as much as we are doing now to reduce climate change, which is about nothing," Smith writes in an e-mail. "So it's the worst case that has been modeled, but it's also the future we're currently headed toward."

This could have all sorts of negative ramifications, though St. Louis' geography means it will avoid rising sea levels while the Mississippi and Missouri rivers will stave off dire water shortages. Smith warns, however, that even those waterways could wither from both climate change and increased water usage upstream.

"Storms will be more intense, and dry periods between storms will be longer," he writes. "So we'll have a regular flood/drought cycle like we did two years ago when barge traffic was almost stopped on the Mississippi, and then a few weeks later it was flooding."

Andrew Wyatt, vice president of horticulture at the Missouri Botanical Garden, says the new temperate conditions would give St. Louisans a chance to plant warm-weather fruit trees like nectarines and peaches during most months of the year. He also predicts we'll do it through widely scaled vertical gardening, a space-saving farm technique for growing plants, vegetables and even forests on the sides of buildings. We'll need that new farm space to account for St. Louis 2114's denser population and stretched water resources.

"People might be living in smaller houses, smaller dwellings, and instead of a yard you'll have more of a vertical garden," says Wyatt.

Practical limitations in watering, weeding and maintaining vertical gardens hold these designs back today, but Wyatt thinks that in the future we will have the technology to create a St. Louis skyline blooming with produce.

Rising temperatures will also affect the area's animal ecology. Armadillo sightings have already become normal summer occurrences in Missouri. In a century, if they can make the transition from rural to urban dwellers, armadillos could become for us what rats and pigeons are for New York City.

—Danny Wicentowski

Sorry, St. Louis — there won't be flying cars in 100 years.

"It would just take too much energy, and traffic would just be a mess," explains Shawn Leight, vice president of traffic and engineering firm Crawford, Bunte, Brammeier, and an adjunct professor at Washington University.

But there will be big changes. How those changes develop, Leight says, depends on one question: "Will St. Louis turn back in and redevelop our core, or are we going to continue to expand outward?"

If St. Louis expands outward, cars will still rule the day — we just won't be driving them.

"The personal vehicle won't go away. There's too much freedom, too much independence there," Leight says. "A really big change that will happen in the next 20 to 30 years is automated cars."

By the year 2114, Leight predicts, all cars will drive themselves. Accident rates and fatalities should plummet, but the city's roads will be changed as well.

"Today, most lanes are twelve feet wide. If cars drive much more precisely, then we won't need lanes that wide," Leight says.

This is all great news, but self-driving cars also mean no more highway-patrol officers writing revenue-generating tickets. More sustainable fuel sources mean fewer funds from gas taxes. So if St. Louis sprawls, how will we pay for those new roads? One major idea that's being debated in the federal government is charging people a per-mile tax.

"The concern of that is Big Brother," Leight says.

Cars of the future are expected to be data-collecting supermachines. It's happening now. Little black boxes that record mileage, speed prior to accidents and other data are installed in more than 90 percent of new cars. As the data-collecting technology improves, revenue-generating uses for that data will increase. Privacy experts are wary of the potential for abuse.

"In 100 years the worst-case scenario is our cars will know where we are, where we've been and where we're going," says Nate Cardozo, an attorney with the Electronic Frontier Foundation. "They'll be sharing our data with private companies, advertisers, insurers, law enforcement, jealous ex-spouses, you name it."

If St. Louis turns inward, on the other hand, the future of transportation doesn't look quite so dystopian. Leight — whose firm currently consults with the Missouri Department of Transportation — says the development of north city will play a crucial role in how transportation changes in St. Louis.

"Infill developments, like Paul McKee's North Side Regeneration Project, are a big deal because redevelopment in the city results in higher densities, making public transportation — buses, rails, trolleys — much more effective," Leight says.

Despite the rapid changes in technology that are in store for the next 100 years, Leight says, the way St. Louisans get around won't be that different — it will just be better.

"People think transportation 100 years ago was fundamentally different, but it wasn't really," he says. "Back then we had steam-

engine trains, trolleys, Model T's. Now we have

diesel-electric trains, the Metro and, soon, automated cars."

—Ray Downs

One could say the future of transportation technology is already here.

"The city can stop waiting for flying cars — or even electric cars — because the transportation mode of the future taking hold in prosperous cities around the world is the humble bicycle," says Tom Fucoloro, a St. Louis native who now runs Seattle Bike Blog.

St. Louis has a twenty-year plan to connect the city, county and urbanized St. Charles County with 1,000 miles in bike lanes, which cycle enthusiasts say will drastically reduce the need for car travel a century from now.

"Fifty years from now, 100 years from now, it won't be a big deal to ride your bike home or to work," says Susan K. Trautman, executive director at Great Rivers Greenway. More bike lanes and trails will make getting from neighborhood to neighborhood easier and safer. "I think St. Louis in 100 years will feel very different. You'll be able to connect in ways you can't right now."

Trautman and Fucoloro imagine a future where a typical St. Louis child could rely on her bike, not cars and buses, to get to school. By the time she turns sixteen, she'll already be able to get around the city independently without getting her license.

Biking will also go a long way toward fighting the public-health concerns — diabetes, heart disease, obesity — that plague us today.

"All of a sudden, you've got this very vibrant, happy place where people are getting around and mixing it up," Trautman says.

—Lindsay Toler

By day, Dr. Eric Leuthardt is a neurosurgeon and the director of the Center for Innovation in Neuroscience and Technology at Washington University. By night, he's a science-fiction author — his first novel, Red Devil 4, just came out this month. That means he spends his free time imagining all the future applications of the devices and procedures he uses in the lab now.

"Right now a common term people love to throw around is 'quantitative self.' That's kind of the whole movement where people wear electronics to monitor their physiology — Fitbits, FuelBands, Google Glass, cameras and video feeds on our faces," he says. "I think that we're going to get closer and closer to the point when it becomes very low risk to have either a procedure or something noninvasive done to you where you can access your brain."

Leuthardt works on computer interfaces that can communicate with the brain and help restore function to people with different types of disabilities — accident victims, stroke patients, those with Alzheimer's. He works to help these patients control things with nothing but their thoughts. Through this research, he has already demonstrated that the brain can send out signals that are understandable to computers: He once had a patient whose brain was connected to electrodes play a game of Space Invaders by thinking about his moves. Leuthardt reasons that if our brains can send signals out to a computer, there's no reason a computer can't send signals in.

"Imagine you're completely connected to the Internet. If you want to talk to a person you just think about it. You literally exchange thoughts and information, literally at the blink of an eye — actually faster than the blink of an eye," he says.

Whether that takes the form of an implanted chip or more advanced forms of wearable technology, Leuthardt predicts that once it's possible to stream information into and out of our brains, everyone will be clamoring for the technology.

"Imagine this — you have two lawyers. One lawyer has an implant that will give him more rapid access to information. You know that other lawyer is going to get that implant, too," he says.

A downloadable brain will have lots of legal and ethical ramifications as well: Will implants be allowed in school? Will law enforcement need a warrant for our minds? What if criminals can hack us and make us do things — are we responsible for our actions?

Here's another question: Where is all this amazing and simultaneously morally fraught technology going to come from? From St. Louis, according to Leuthardt.

"This city could be the new Silicon Valley for neuroprosthetics or Silicon Valley for neurotech — we have that capability in terms of we are some of the leaders in developing the technology," he says. "It could be what makes this city in the next generation of corporations and industry. We have at least the potential, if the city gets it right, to really be the leaders in that."

—Jessica Lussenhop

Shibu Jose is known to his colleagues as the guy with the rose-colored glasses, although green is probably a more accurate shade. He's a professor with the University of Missouri's College of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources and its Center for Agroforestry, and he has a plan for making the area around the Missouri and Mississippi rivers into the largest clean-energy economy in the nation.

Jose's vision is to turn the Missouri and Mississippi river-bottom areas into cropland for a variety of plants that could be made into sustainable biofuels (known as "advanced biofuels"). Currently, the land is either floodplain or marginally productive cropland used mainly for corn and soybeans. Jose wants to plant the river bottoms with sustainable biomass feedstock — plants such as sorghum, switchgrass, poplars and willows.

In order to process this river-bottom biomass, he proposes creating a network of small-scale rural refineries throughout the area. This processed material would then travel, via the river, to larger hubs where it would be made into fuel. Because of its location in the center of the country, the Mississippi and Missouri river cooridor could serve as the hub of this advanced biofuel production, shipping the fuel out to the coasts and placing us in the center of a green-energy revolution. We could create a Midwestern "Persian Gulf of advanced biofuels," Jose says.

Dan Burkhardt, owner of Bethlehem Valley Vineyards and founder of the conservation organization Magnificent Missouri, sees the potential in Jose's plan.

"Conservationists don't do well when they ask farmers to let their productive land sit there as a wildlife habitat or green space," he says. "Farmers need to make a living, and if this is a way for them to grow an alternative crop that is better for the environment, reduces the use of pesticides and helps with soil erosion, it's a net gain."

Most of the crops Jose proposes planting are perennials and hold the soil in place. Because they do not need to be replanted yearly, they reduce soil disturbance and the accompanying sediment in rivers and streams. Jose believes the idea could actually clean up our water bodies. And he's optimistic that the time will come when the world uses 100 percent biofuels.

"Why not?" he says. "It took nature millions of years to convert biomass into petroleum. We have the technology today to convert biomass to petroleum in a matter of seconds."

—Cheryl Baehr

When we spoke to neurosurgeon and science-fiction author Dr. Eric Leuthardt about computer implants in the brain that could be invented right here in St. Louis, he told us accessing the Internet could be a little bit like stepping into virtual reality. Experiences could be "as downloadable as iTunes."

Naturally, our juvenile minds jumped straight to pornography.

"As neuroprosthestics becomes the next console people use to see and feel things virtually, they will naturally pursue experiences that they could otherwise not do," he wrote us in a followup e-mail. "Some people will choose skydiving, others will choose driving a racecar and then there will be the rest of the human population that will...er...uh...choose something a little more risqué."

The sexperts tend to agree with him — that 100 years in the future, we'll feed our lust using virtual technology, digital stimulation, robots with artificial intelligence and "fake" girlfriends and boyfriends.

"We've always been into objects," says Linda Weiner, a sex therapist in St. Louis. "But the objects will change. I think the most intense need is to invent something that will create desire in our stressed-out lives."

Weiner sees a future where St. Louis tech companies build sex robots that re-create human touch and bonding, haptic machines will allow us to have and watch live sex with partners who are vast distances away, and even artificial orgasms that can be injected directly into the brain. Weiner thinks we'll eventually be able to morph our bodies, so anyone can experience sex as a different gender. Because the technologies will still be novel and taboo, "it will be extremely erotic," Weiner says.

Is St. Louis ready to invent the sex robot? "We invented ice cream and racquetball," Weiner says. "We've got some Internet geniuses from St. Louis."

But what if you don't want futuristic sex? What if you're into good old-fashioned petting with another flesh-and-blood human? Matt Homann, the St. Louis inventor of Invisible Girlfriend and Invisible Boyfriend, the startup that produces online evidence of a fictional relationship, had a surprisingly quaint thought on the subject of future sex.

"Two more generations from now, we'll certainly have the capacity to livestream our every moment," he says. "The digital tools are there for them to experience sex directly wired into their brains, but there are going to be people, the 2114 hipsters, who prefer the analog and unplug."

—Lindsay Toler

Great German brewers built the city's identity over the last two centuries, and there's no reason to believe the next 100 years will be any different. But will the 4 Hands and Schlaflys of today become the Anheuser-Busches of tomorrow?

"There have been so many craft beers launched in the last few years, and I don't see how most of them will survive," says Bill Finnie, who headed a number of sweeping beer-industry studies during his three-decade career with A-B.

Now an adjunct professor at the Olin Business School at Washington University, Finnie points out that in the late '50s and '60s, numerous successful regional breweries — like Falstaff in St. Louis — failed. They couldn't complete with the low-priced beers from massive consolidated breweries like Anheuser-Busch, Budweiser, Miller, Schlitz and others.

"Craft beer is an amazing transformation, and I think there's another fifteen years for it to run," he says. "I'd say 80 to 90 percent of the craft beers launched over the past five or six years will not be around five or six years from now."

Schlafly cofounder Dan Kopman, however, is looking far beyond five or six years. By 2114, he predicts, high-efficiency brewing methods will reduce the time and water needed to produce a barrel of beer.

"Water is becoming scarce in some parts of the world," Kopman writes in an e-mail. "Essentially, all of the effort around the world to conserve fresh water and the use of desalination will impact brewers."

But other advances will allow St. Louis brewers to push the definition of beer itself.

"Who is to say that beer should be made from only barley and wheat, hops and specific yeast strains?" he suggests.

The future definition of "beer" could become more of a subjective descriptor; we could be brewing with cane and beet sugar, honey, fruit juices, spices, new yeast strains and other enzymes — all will result in uniquely different flavors we don't even have words for yet, according to Kopman.

"We are seeing brewers use other spices/flavorings in beer more and more," he writes. "In addition, brewers will use nontraditional yeast strains and other forms of bacteria to ferment sugar liquids. This will result in different flavors, and traditional definitions for beer will be stretched."

For Finnie, though, the most stunning development in the future of beer won't come in a bottle — it'll be in our brains. Alzheimer's research, he says, may eventually lead scientists to solve all kinds of disorders that originate in the brain — even addiction.

"I am optimistic that, in the future, you can have the socialization and good aspects of alcohol without the tragic aspects of alcohol abuse," he says. "I'm an optimist. I think the world is going to be pretty darn good."

—Danny Wicentowski