Around 10 p.m. on August 4, 2021, a St. Louis man named Jeff cracked open his bedroom window to smoke a joint. Looking outside onto his street in Marine Villa, he noticed his Jeep's brake lights glowing in the dark.

Someone was in his car.

He hustled outside, filming on his phone. The Jeep's driver-side door was open and the woman standing next to it wore a guilty look. A black mask covered her nose and mouth, and a ball cap sat backwards atop her head. Her eyes went wide with surprise.

"What the fuck?" said Jeff.

"My friend sent me over here and told me that I could use his car because my car broke down," said the woman. "I'm so sorry, is this not my car?"

Incredulous, Jeff looked down to see that a screwdriver, hammer and other tools he had stored in his Jeep were strewn about on the ground. "What is all this?"

"These were all in here," the woman replied.

"Yeah, in my fucking car."

She walked around to the passenger side door, before beginning to open it. "My purse is in there," she explained.

"I don't give a fuck!" Jeff erupted.

After a brief confrontation that nearly turned physical, he let her have her purse, and she walked off into the night, muttering about how everything was a misunderstanding.

Jeff went through the car to see if anything had been stolen. He found a bag with three orange pill bottles, including anti-anxiety medication. They were prescribed to someone named William Overturf.

Jeff called the number beneath Overturf's name. He told him the situation, and threatened to notify law enforcement. Overturf said he had just gotten out of prison and didn't want anything to do with whatever was going on.

"Anything that's in there that's mine you can have," said Overturf, according to Jeff.

Jeff asked him for the identity of the woman who tried to steal his car. Overturf said her name was Elizabeth Cooke.

Thus began the saga of Elizabeth Cooke, which was in fact the woman's real name. William Overturf is her real-life fiancé.

Jeff, however, is not the real name of the man who caught Cooke in the act. He agreed to speak with the Riverfront Times only on the condition that we give him a pseudonym.

In the coming months, the aftermath of this alleged attempted carjacking would turn Cooke's life upside down, putting thousands of true-crime obsessives and would-be gumshoes on her tail, and propelling her from an impoverished petty criminal into a tabloid-style celebrity.

It all happened because, when she left the scene, she forgot her smartphone.

Jeff got the passcode from Overturf, the former said, and quickly accessed the phone's contents. He couldn't believe what he found. Beyond lurid messages relating to drugs and sex, it appeared to show evidence of a massive, St. Louis-based criminal ring.

And so Jeff decided to seek vigilante justice. Over the next week and a half, he posted tons of content from 35-year-old Cooke's phone onto the internet.

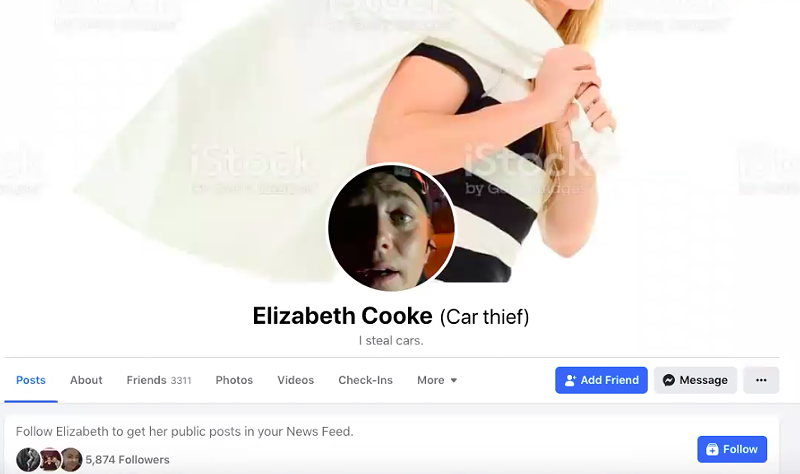

Hacking into Cooke's Facebook account, Jeff posted the video he took of her trying to steal his car. Then he changed her account's name to "Elizabeth Cooke (Car Thief)."

Her new account description? "I steal cars."

He discovered messages on her phone relating to other stolen automobiles and began posting them on Nextdoor. He wanted to help those whose cars had been stolen get them back, he said.

On Facebook, Jeff also posted one of Cooke's private conversations with a meth dealer, one with a guy who seemed to fence stolen electronics, and one about a plan to break into storage lockers. Jeff further uploaded what appeared to be her web-browsing history, which included a video titled "How to hotwire a car quickly and easily!"

Cooke's Facebook friends numbered about 1,500 at that point, Jeff said. They began sharing her page, and it went viral.

"So I started posting more and more," Jeff says. (He notes that he didn't post everything, however, and set photos of her young son to private.)

After going through Cooke's now-public messages, one woman recognized her husband's missing Cadillac. "That's my volvo!!" another woman posted, adding: "I called the cops immediately and the car came back FULL of cheap women's flip flops!"

Cooke's actual friends had no idea what was going on. "Liz...What are you doing???!!!" one posted. "I cannot believe this is you! It's very sad and I really hope you get your life together!"

Jeff recorded Cooke's screen as he scrolled through her archived messages. He posted the videos to YouTube, creating about two hours of content for anyone wanting an even deeper dive.

Tens of thousands of people across the internet began tuning in, enthralled by this ultimate doxxing. At a time when St. Louis car robberies were rising — in 2021, some areas saw catalytic converter theft rise 300% — city residents cheered him on.

"Keep it up," someone wrote to Jeff on Cooke's Facebook page. "You're a fucking hero."

People began posting Cooke-themed memes. There was Cooke stealing all of the copper from a construction site, and Cooke holding hands with Kid Rock. Someone made a mock movie poster of her in Ocean's Eleven, and another of an imaginary film called House of a Thousand Key Fobs.

Others in Cooke's circle began gaining fame and infamy as well, including a friend who called herself "Gypsy Jen" and another dubbed the "Meth Magician." The latter was given this sobriquet after followers of Cooke's story uncovered his TikTok account, in which he performed magic tricks. (The "Meth" part came from his frequent references to "zips," "ounces," and "re-ups" in leaked text messages.)

Around August 9, Cooke finally got wind of what was happening. "They're posting everything," someone texted her, on a different phone. "All your drug deals and all that shit."

"That was my personal life," Cooke later tells me, angrily. "The whole world knows who I am."

And so Cooke decided she needed to get out of St. Louis. On August 10, she took off in a stolen car to see her fiancé Overturf, who was staying with his mother in western Illinois.

But she never made it. When she pulled off Interstate 55, the car broke down. Someone called the police on the "suspicious vehicle" and Cooke was arrested — and charged with possession of a stolen vehicle, possession of methamphetamine and possession of burglary tools.

But Cooke's problems were just beginning. While all of this was happening, a growing cadre of internet detectives had come to the conclusion that she was guilty of a much more serious crime: murder.

Elizabeth Cooke grew up in the Patch neighborhood in south St. Louis, as well as parts of St. Francois and Franklin counties in rural Missouri.

"I consider myself half from the city, half from the country," she says. "My family doesn't do drugs. They don't get in trouble. They work. They take care of their kids."

She describes herself as the black sheep, a troublemaker out of step with her more straight-laced family members. (Considering her affinity for tie-dye, however, she prefers "rainbow sheep.")

Information about Cooke's young adult life is hard to come by, but by 2017 she was spending significant time at regional music festivals. At the Astral Valley Art Park, an Ozarks events space with psychedelic art displays, she met a friend named Abby, who asked the Riverfront Times not to print her last name.

According to Abby, she and Cooke shared dark pasts, having each experienced abuse and addiction. Their troubled backgrounds helped them bond immediately.

"Elizabeth offered me a place to stay rent free till I could find a job," Abby said, adding that Cooke also offered to host her daughter. She added that Cooke often spoke about opening a crisis center and safe house, to help women start over.

Without Cooke, she "would have ended up ... either dead because of an OD or worse," Abby says. "This girl can be so charming, so uplifting. She shines when people need her."

This description stands in stark contrast to the persona portrayed on Cooke's hacked Facebook page. Indeed, in the years following her music festival job, Cooke's life began coming apart. A friend named Leslie Stevenson said Cooke eked out an existence dumpster diving, doing what she could to turn other people's trash into a living.

Tony Callesis, the manager of the Storage of America facility in Dutchtown where Cooke stashed many of her dumpster finds, said he once looked out the back window of his south-city apartment to see Cooke putting on goggles and a helmet with a light affixed to it — like a coal miner. She proceeded to throw herself into his alley's dumpster, and then closed the lid.

According to Cooke, in May 2020, she began staying at the St. Louis Eco Village, a north-city hippie-style commune that also serves as a nonprofit providing unhoused people with access to showers, meals and other essentials. Eco Village also operates an Airbnb to help fund their work.

According to Yvonne "Jazz" Berry, who runs the Eco Village, Cooke rented the Airbnb for three weeks in November 2020, but afterwards refused to leave, citing squatter's rights. (To the Riverfront Times, Cooke denied this, saying she moved in months before that, never mentioned squatter's rights and that in lieu of rent she donated items she'd salvaged from dumpsters.)

According to Berry, around Christmas that year a 62-year-old man named Bobby Phillips arrived at Eco Village, along with another man. They had both recently gotten out of prison, and participated in the nonprofit's food share and used the shower.

"It's the middle of winter," Berry recalls telling them. "Yeah, you guys can crash on the couch."

Cooke says she met Phillips when her friends brought him along dumpster diving. Another night, she came back to Eco Village and found him sitting alone in a cold, dark room. She gave him blankets and food.

The pair began to bond; he appears to have tried to impress the younger woman by claiming money was coming his way. Cooke says that, around Christmas, Phillips told her he was going to include her in his will.

"[H]e made me ... executor of estates and power of attorney," Cooke wrote, in a leaked message. "He left me a lawsuit worth $1.7 million it just hasn't settled yet."

On January 1, 2021, Phillips died from cardiovascular disease exacerbated by methamphetamine, according to the St. Louis City Medical Examiner.

Cooke's involvement, if any, was not immediately clear. Later that day, Cooke filmed a video of herself discussing Phillips. In it, she wore a T-shirt with astral designs. Behind her were piles of clothes and a giant white teddy bear.

Phillips endured childhood abuse, Cooke says in the video, before spending decades in prison. There he learned how to read and write, and studied law.

"[Phillips] pulled my heartstrings," she says.

Seven months later, when Jeff began sorting through the contents of Cooke's phone, he found the video as well as photos of other items belonging to Phillips, including his social security card, his birth certificate, his ID, documents signing over Phillips' power of attorney to Cooke, and documents naming Cooke as the sole beneficiary in Phillips' will.

Jeff posted them all, and soon received a message from a man named Mike Clingman, claiming that around Christmas Cooke and others gave "an old guy" a "hot shot" of drugs. Cooke was under the impression the man had money, said Clingman.

Jeff soon wrote on Cooke's Facebook page: "I think I may have uncovered a murder ya'll."

From this point forward, the online Cooke sleuths were no longer just trying to help victims get back their stolen property — they thought of themselves as avenging a murdered man.

Their intensity ramped up accordingly. They ran with the narrative that, not long after Phillips wrote Cooke into his will, Cooke (or perhaps an accomplice) administered an intentionally lethal dose of illicit drugs, killing Phillips in an effort to hasten the windfall's arrival.

A week and a half after Jeff hacked Cooke's phone, Facebook finally locked him out. But those interested in her case had already migrated to other forums, including Facebook groups dedicated to investigating her, numbering some 80,000 members all told.

One group released a poll asking if Cooke killed Phillips.

"Yes! The evidence is overwhelming" won in a landslide.

I first became aware of Cooke in mid-August, around the same time seemingly every other St. Louisan did. I came to her story through Reddit, but it was already circulating in the national media, covered by Fox and CBS affiliates across the country, as well as digital media outlets like the Daily Dot and The Young Turks. Barstool Sports ran the lengthy headline, "The Most White Trash St. Louis Whodunit Of Our Time Is Unfolding On Facebook And It Has Everything - Murder, Drugs, Thefts, Junkies Doing Magic And More."

I visited Eco Village, where volunteers were overwhelmed by the sudden swell of attention, not to mention furious about online accusations that they had somehow abetted a murder.

I later spoke by phone to Cooke, who was locked up in Macoupin County Jail in western Illinois, about halfway between St. Louis and Springfield. She remained upset about the doxxing, but acknowledged the veracity of the content Jeff had spilled online.

"I was a drug addict," she says. "When you're texting someone you're not sitting there thinking, 'One day is someone going to get ahold of my phone and everyone's going to see this?' I'm doing what I had to do to survive, whether it's finding some way to get high or finding a ride to get somewhere."

Though Jeff's postings may have made her seem like a crime kingpin, she resided on the far fringes of that world, she claims. "They made me out to be a ringleader," she says. "I'm no ringleader."

Lacking internet access in jail, Cooke's only mode of communication with the outside world was prepaid phone calls and "Jail Chirp" text messages, running ten cents each. She sounded frantic and distraught during this time, overwhelmed by her sudden infamy. Someone had called the Department of Family Services on her sister, she said. It was intended as a prank, pulled for no reason other than her sister's relation to Elizabeth Cooke.

Cooke feared that, in jail, she couldn't make payments on her storage units in St. Louis and Illinois, risking everything she owned, including a Beanie Baby with a misprint tag she says was worth $80,000.

She wholeheartedly denies having anything to do with Phillips' death. "I wasn't even on the same floor [of Eco Village] when he collapsed," she says

The St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department also doesn't seem to have taken her seriously as a suspect. Cooke says she was never contacted by them about Phillips, and Jeff says his only interactions with police were when they confiscated Cooke's phone. St. Louis police spokesperson Evita Caldwell says an investigation is still active, but would not disclose further details.

According to St. Louis police Officer Sean Martini's report on Phillips' death, medics arrived at Eco Village around 10 a.m. on January 1 last year to find Phillips on the floor, unconscious but with a slight pulse.

Medics were ready to start procedures they hoped would save Phillips' life when Cooke produced paperwork showing he had recently signed over power of attorney to her. The paperwork stated that Phillips did not wish to be resuscitated. The medics ceased their efforts, and Phillips died soon after.

Phillips' body was initially picked up from Eco Village by a funeral home, but the St. Louis City Medical Examiner considered the death suspicious and took possession of the body. The medical examiner later ruled the death to be accidental, and released Phillips' body to another funeral home, in Illinois, where he was cremated. His ashes were given to Cooke.

Despite no smoking-gun evidence against Cooke, the thousands of amateur sleuths investigating her continued bearing down.

On a sunny Sunday in August, a group of them emerged from the internet into a small vape shop in Lemay to compare notes. On the sales floor were glass cases displaying bongs, vapes and Trailer Park Boys rolling trays.

About a dozen people arrived, including Jeff. Cameras rolled as well; a production company had offered Jeff a producer credit to tell Cooke's story, and so he was recording for a potential true-crime documentary.

Brock Schmittler, a large and boisterous man with tattooed arms who had been invited by Jeff to spread word about the case, called the meeting to order.

The group explored theories about what might have happened to Bobby Phillips, discussing Cooke's messages with a woman called Gypsy Jen shortly after Phillips' death. Phillips was the perfect mark for an elaborate honeypot scheme aiming to steal his incoming fortune, the group speculated. Cooke and Gypsy Jen may have been among those responsible for his demise.

"Bobby falls in love easily with Elizabeth because she's young, she's attractive," Schmittler theorized.

Schmittler, Jeff and the others were particularly preoccupied with the whereabouts of Phillips' ashes. They wanted them returned to Phillips' daughter.

Indeed, for many in this group, and on the internet, Phillips' daughter was another victim in this case. The Riverfront Times reached out to her, and she agreed to speak with us, so long as we didn't use her name.

Phillips was only an adolescent when he first got caught up in the justice system. "He spent the rest of his life bouncing in and out of prison," his daughter says. In his twenties, Phillips was working as a carny in Missouri when he was arrested for burglary. Because he'd previously committed many petty crimes, he drew a lengthy sentence. For years he wrote to his daughter every week, she says; the letters came with elaborate doodles.

In prison, "Bobby read and studied criminal and civil law a lot," says Roderick Choisser, an inmate at Western Illinois Correctional Center, who was previously incarcerated with Phillips. "He was at constant war with different prison administrations. Instead of his fists, he used civil action."

Phillips was litigious. In one lawsuit, he sued the Illinois prison system for forcing him to eat nonkosher food, which, he said, was an affront to his Orthodox Jewish faith. He even went on hunger strike.

The suit was unsuccessful; Phillips' daughter says that Phillips wasn't actually Jewish. In another suit Phillips claimed he was in danger from various prison gangs, as well as from inmates named Snake and Shaky John.

Phillips also sued Wexford Health Services, the prison health-care provider, over inadequate treatment for his hepatitis C. The suit began in 2008 and is still crawling its way through the courts. The supposed impending $1.7 million settlement he mentioned to Cooke referred to this case.

"When I heard there was a big lawsuit and money was going to her, I had to giggle," Phillips' daughter says. "I've heard that my entire life. It's always been, 'I have a big account set aside for you.'"

"Bobby lied to Cooke to impress her," Jeff maintains. "It got him killed."

On October 14, Elizabeth Cooke was released from Macoupin County Jail. For the stolen car and possession of meth charges she was given probation and time served.

Hoping to interview her, I offered her a ride from Macoupin County Jail back to St. Louis. She accepted.

By the time I arrived to the small town where the jail is located, Cooke had already walked to a local Walmart, using a map hand-drawn by a fellow inmate. I met her in the checkout aisle. Wearing a purple Members Only-style jacket, she bought some new socks and a new phone to replace the one taken by Jeff. We headed back to the jail so Cooke could pick up the items she'd been arrested with.

"Thank you," Cooke said to the jailer after signing for her possessions. "I hope to never see you again."

As we drove back to St. Louis, Cooke apologized for her scattered train of thought. She has ADHD, she says, and proceeded to talk at length about tarot cards, reincarnation and spirituality. Humanity was suppressed long ago, she maintains, leaving us out of touch with our true potential.

After a long period of sobriety, Cooke had resumed drinking in recent years, she says, and later quit drinking but started doing hard drugs. During this time period she'd encountered a whirlwind of characters, all seeming to go by nicknames: Nature, Detroit, Bigfoot, Smoke.

She gave Phillips a tarot card reading shortly after they met. "He was blaming himself for a lot of things," she says. "He needed to forgive himself, so that he could move on."

Around Christmas, Cooke says, Phillips mentioned the potential settlement money, saying he would leave it to her so she could start the women's shelter she often talked about. Signing over his power of attorney had been his idea, Cooke says.

On New Year's Eve they went dumpster diving. Phillips, she says, "was like a kid in a candy store." In the dumpster Cooke found a white teddy bear, the same one in the background of the video she later recorded about Phillips.

The next day she and Phillips were planning to take their dumpster items to her storage unit. But when Cooke came downstairs to collect him, she found him collapsed on the floor, she says.

She claims it was his true desire not to be resuscitated. "Bobby told me that whenever he went he was ready to go," Cooke says.

She told me this as we whizzed past southern Illinois farmland, giving the account with her typical manic intensity. It seemed hard to fathom that anyone lying could speak so fast while keeping their facts straight.

As the Arch came into sight, Cooke turned her thoughts to the man she considered her archenemy: Jeff.

It bothers her that he has maintained his anonymity, even after pouring every detail of her life online. "He has fifteen years of my photos," she says. "I have not one photo of my child."

Back in south St. Louis, outside a post office where she picked up her mail, Cooke notes she'd been up and down every alley in the neighborhood, and maintained a mental map of which dumpsters were worthy of deep dives. She picks a few berries off a plant hanging over someone's fence. "That house always had the best garden," she says.

At one point, however, Cooke's sense of direction falters. She struggles to find the friend's house where she planned to crash. She knows St. Louis by its alleys, she says, not by its streets.

In the weeks following her return from jail, Cooke and William Overturf, her fiancé, clean vacant house construction sites in exchange for being allowed to sleep in the houses. They usually go without heat or electricity.

Cooke texts and calls me from time to time, usually either asking for a few bucks or a ride. I only give Cooke cash once, for cab fare after an interview.

In one of our conversations, she says someone she didn't know recognized her on the street, accosted her and shoved a phone in her face, recording video.

She also says she's been attacked twice by acquaintances pissed that their messages with her had gone public. One assailant wielded a baseball bat.

"People read what was posted online," she says. "They're pissed off about that shit. I'd be pissed too."

Cooke says she can't get legitimate work because of her criminal history, not to mention her Google search results.

She spent several days cleaning someone's yard for $40. Slowly, she has come to grips that the $1.7 million is not coming to her.

In January 2022, a storage unit Cooke had rented — but had missed payments on — was going up for auction. Jeff planned to buy it, hoping to find Bobby Phillips' ashes and return them to Phillips' family.

At the last minute, however, Cooke produced the necessary cash to keep the unit.

"I don't know how she did it," says Jeff.

And yet Cooke claims she no longer possesses Phillips' ashes. She says they were among contents she'd loaded onto a U-Haul truck, which U-Haul repossessed against her will, disposing of the ashes and everything else.

Phillips' daughter tells me she doesn't know what to think about the "conspiracies" surrounding Cooke and her father. Getting Phillips' ashes back, she says, is her main priority. Her mother died a few months before Phillips, and she had hoped to keep their remains together.

When I tell her that Cooke claims not to have the ashes, Phillips' daughter sounds flummoxed. "It sounds like [Cooke] did what she did best and got herself another storage unit and ..." she begins, before trailing off.

I spoke to Mike Clingman when the Cooke story first broke, but hadn't been able to follow up with him. He was a critical character in her trajectory, having ignited the murder conspiracy by alleging that Cooke and others had administered a "hot shot" to Phillips.

After weeks of texting, in mid-November I finally received a message back from his phone, sent by his fiancé. "Mike can't contact you," it read. He had died a week earlier, from COVID-19 exacerbated by methamphetamine, according to the Jefferson County Sheriff's Office.

Clingman and Cooke had met one day when the latter's car broke down in front of Clingman's dad's house. Clingman gave her rides from time to time.

Even though Clingman had stoked the online sleuths' murder theories, Cooke called him a friend. "Mike has a good heart," she told me before he died. "He really does."

In the summer of 2020, before Elizabeth Cooke met Bobby Phillips or Jeff, she made a video that now seems eerily prescient.

Speaking at Eco Village into her phone's camera, she mimics life as a celebrity. "Has anybody seen my show yet? It's called Life with Liz. I'm going to be fucking famous."

"I was [feeling] happy and goofy," she remembers later, about the video.

She indeed got famous, yet in the most destructive — and the most fleeting — ways possible. Six months after her story captivated true crime fans around the country, the online pages dedicated to her are now ghost towns. "When we realized that no one was submitting tips to us — it was more like, 'Let's make this funny meme' — we realized this wasn't going to go anywhere," Jeff says.

But Cooke's anger over her doxxing remains. "My life is shit right now," she says. "I'm in the cold, getting kicked out of vacant houses because I have nowhere to go."

One can understand the public's desire to solve a murder, and to hold the guilty party accountable. And yet, when I drove Cooke back from jail, she didn't come off as a conniving, criminal mastermind. She seemed like a free spirit who at some point had become un-moored. She struck me as tragic.

After she told me she was crashing at a friend's place in south St. Louis, I offered to drop her off at the house. She declined, however, not wanting me to know her exact location. And so, at her request, I let her off at the end of an alley.

"Thanks for the ride," she said, departing.

I waved goodbye, and prepared to drive away. After a beat, however, my curiosity got the best of me.

I turned around and peered down the alley, wondering where she was headed. But I couldn't see her. Cooke had already disappeared.

Additional reporting by Daniel Hill and Doyle Murphy

An earlier version of this article mistakenly stated that Elizabeth Cooke traveled with a performance group from Astral Valley Art Park. We regret the error.