On the morning of May 24, Barbara Oswald visited Trapnell in prison in Marion. She'd visited seven previous times that month, four times with at least one daughter in tow. Her eighth visit would be her last.

Trapnell, skyjacker and supercon, was six years into a life sentence connected to a 1972 hijacking and ransom attempt — he'd smuggled a pistol on a plane as part of a caper that ended when he was shot by an FBI agent. Still, Oswald found the jailed Trapnell just as captivating as the book had promised, and in a few months her feelings for the skyjacker deepened to absolute loyalty. He promised her a life together. In Australia, he said, the laws couldn't touch them. He showed her a photo of the house where they'd live. She believed him.

After conferring with Trapnell, she drove back to St. Louis that day and packed a briefcase full of guns.

Then, at 5:25 p.m., Oswald arrived at Fostaire Helicopters for her flight with Barklage.

Earlier that week, she'd called in a reservation under the pretense that she was a real estate agent looking at flooded property near Cape Girardeau. In a statement submitted to the coroner's inquest, Barklage described her demeanor as friendly, even talkative.

But half an hour into the flight, Oswald reached into the briefcase and pulled out a pistol. She disconnected Barklage's radio and put the gun to his head. She told him to fly east.

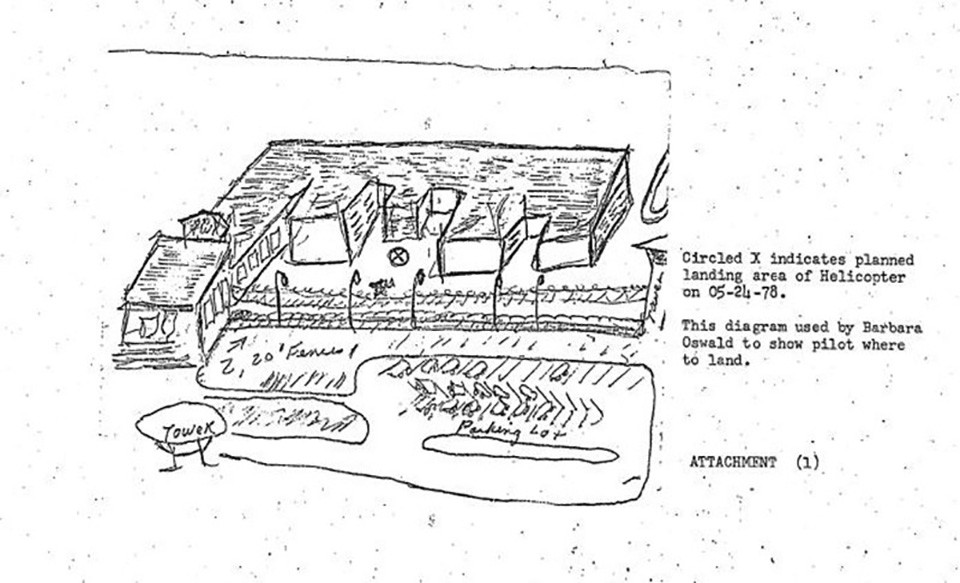

Cape Girardeau is 30 miles from Marion, a short hop for a helicopter. Oswald informed Barklage of the basics: They were picking up three prisoners at the federal penitentiary. In her pocket she carried a hand-drawn map; it showed a rough approximation of the prison yard. She'd made an 'X' on the spot where she wanted Barklage to land the craft.

Barklage later described his calculations for survival: He considered the prison, its tall guard towers and assuredly armed officers. He didn't trust Oswald or the three prisoners. He did trust the guards to try to shoot down all of them.

Barklage claimed he tried to talk Oswald out of it, but, he said, "it was to no avail." So he started his own scheme.

In Barklage's statement, he describes offering unprompted advice. The side door was heavy and difficult to open, he told her. Opening it in the air, he said, would save precious moments on the ground.

She believed him, and leaned forward to work the door's handle. Barklage recounted: "While she was trying to open the door, she put the pistol that she had on me in her left hand, I noticed her finger was not on the trigger."

All of Barklage's combat experience had taken place in the air, but it had generally involved spraying ammunition at ground troops. He'd never engaged an enemy in close combat, let alone disarmed one mid-air.

Still, he made his move, snatching the pistol from Oswald's hand. Of course, he also had to take his hands off the controls. But now he had the pistol.

"The heli was going down," Barklage wrote.

He turned back to the instruments to stabilize the suddenly falling craft, and in the mirror he saw Oswald rummaging in her briefcase. She selected a .45. "Well, I have another," Barklage heard her say.

Barklage turned back around, raised the pistol and fired five times, hitting Oswald twice in the torso and once through the head. A fourth bullet blew a hole in the helicopter's skin.

Barklage turned back once again to regain control of the helicopter. In the mirror, he could see Oswald slumped against the chair, unmoving.

The helicopter landed gently near the prison administration building. Barklage sprinted through the entrance and into a communications room. He stabbed at various buttons on the intercom system, desperately trying to make a call when the first group of guards found him.

Corrections officer Clyde Jones was among that group.

"I met Mr. Barklage right at the front steps," Jones later reported to his superiors. "He was running and waving his arms, he was extremely excited to the point of being incoherent for a few minutes, and I couldn't make it out just what he was trying to say."

Barklage's words came out in a jumble: "Hijacked," "I had to kill her," "She's dead, I know she's dead."

The guards took Barklage outside. The pilot was "in pretty bad shape," Jones wrote. The officer tried to reassure him. "I kept telling him, maybe she's not dead."

Oswald's blood had pooled along the helicopter's outer door, and it dripped from the side, thick and red, leaving drops like melted candle wax on the landing gear. A medical assistant was called, and the pilot and two guards lifted Oswald's limp form and placed her on the grass of the prison yard. She was pronounced dead at 6:35 p.m.

To this day, MR says she cannot reconcile her mother's descent into Trapnell's madness.

After all, Oswald had worked as a prostitute for years to support her family. She had left that life behind, yet suddenly at 43 years old she lost herself in a career sociopath — because of a book? It was all too much.

"Mom was somebody who really knew what was up, and had been around the block a few times. To see her fall underneath Trapnell's spell ..." MR sighs. "I think she just was tired of being alone."

But to MR, the mysteries of her mother's mindset are less troubling than the actions of the man who killed her.

"No one could figure out why he had to shoot her in the head," MR says.

For a long time, MR says, the Oswald children suspected a conspiracy behind Barklage's actions. The coincidence of a decorated Vietnam combat pilot being hired for their mother's flight seemed too outlandish to be real.

Facing new charges for kidnapping and air piracy, Trapnell encouraged the Oswalds' paranoia. In his arguments to the court, Trapnell claimed Barklage was actually in on the escape plan, alleging that the pilot had been paid expressly to ferry the prisoners to Perryville. They planned to leave him handcuffed to his helicopter to cover up the plot, Trapnell said.

The claim fell apart when Barklage took the witness stand. He pointed out that, if not for a 30-minute delay, it would have been Gene Hoffmeyer flying Oswald, not him.

In MR's mind, though, Barklage still went too far. "I think he had other options, and he didn't take them," she says. "I'll believe that until I'm gone."

One of Trapnell's accomplices doesn't agree. Martin McNally, 74, an ex-con now living in St. Louis, has described his mindset in Marion as "pure escape mode." That included the willingness to kill any guards who tried to stop them. Trapnell, he says, was a "phony monster" responsible for enticing and exploiting Oswald — and McNally, too, sees himself as a monster in this story. He admits, "We destroyed a family."

Both convicted skyjackers and residents of the same cell block, McNally and Trapnell had spent months in 1978 plotting their escape. McNally read over Trapnell's letters to Oswald, encouraging the web of lies that ultimately brought her to them in a helicopter.

Today, when asked about best-possible scenarios for that afternoon in 1978, McNally's mind conjures the escapees embarking on an epic crime spree, skyjacking planes and robbing banks in the South. "There's no telling how it would have gone, but we would definitely have been America's most wanted," he says.

And as for Barklage, McNally bears no bitterness.

"Heavens no," the old hijacker says, "He was a hero. He did what he had to do."