Last week’s debut of the Riverfront Times’ dedicated cannabis section reintroduced readers to the case of Jeff Mizanskey, a small-time Sedalia pot dealer sentenced to life in prison in 1994. Although Mizanskey was ultimately freed in 2015 amid public outcry and a governor’s commutation, the law that empowered prosecutors to put a man in prison for life because of non-violent drug charges lived on — and on and on and on.

That persistence is apparent in the data obtained in 2020 by the RFT showing more than 200 drug offenders still serving decade-plus sentences without the possibility for early release or parole.

Their sentences and parole restrictions rival the range of punishments usually meted out to convicted murderers and rapists — an imbalance that Missouri lawmakers recognized when they voted to repeal the so-called “Prior and Persistent Drug Offender” statute in 2017.

Missouri law, however, isn’t so easily fixed. For one thing, the repeal was not retroactive, leaving behind all the drug offenders it had already trapped in prison. But further analysis shows Missouri courts didn’t abandon the statute even after its supposed repeal: Instead, records obtained from the Missouri Department of Corrections list 33 cases after 2017 where drug offenders were sentenced under the pre-2017 law, which mandated a ten-year minimum sentence and no parole for defendants with two prior drug convictions.

One such case is that of Berry Livingston. Already on probation from a previous drug possession case, Livingston was arrested in 2013 and charged with drug trafficking in Warren County.

Livingston, a St. Louis native, was hardly a serious dealer — he tells the RFT that before his arrest for a small amount of methamphetamine, his previously two strikes were for “residue” and a Valium pill police found in his car — but he’d spend the next three years in jail waiting for his case to move through the court system.

That wouldn’t happen until April 2017. At trial, a jury found him guilty on the new drug charge, but by then, he was on the other side of the repeal that had finally replaced the “prior and persistent” designation after years of work by drug law reformers and lawmakers.

Livingston believed his case came with a chance at parole, and he had good reason to: The charging documents showed he'd been charged under the post-2017 sentencing laws. He’d also faced a parole board.

“I wasn’t in prison very long, maybe a month-and-a-half, and I got a response from [probation and parole] that I would be released in a year,” he recalls now. “I was grateful. My dad was dying of brain cancer; my mom’s health wasn’t much better. I called them and told them I had a parole day, that I had credit for time served, and I’d be coming home.”

In October 2017, six months after his sentencing, Livingston finally received an official letter clarifying his parole eligibility — but the letter’s contents were devastating. His earliest release date wasn’t a few months or a year away, but given as December 8, 2025.

“You don’t know how hard it was to tell my parents I wasn’t coming home,” he says. “Mom was depending on that, and I couldn’t be there for them when I should have.”

Livingston tried to appeal the parole decision, arguing that his case should be judged under the post-2017 sentencing rules. But his arrest had taken place in 2013, when the old rules were in effect — and as many drug offenders have discovered, the 2017 repeal was not retroactive to old cases.

Livingston would spend the next several years mounting legal appeals, and he would become just one of three known “prior and persistent” offenders to successfully argue their way to parole eligibility and eventual release in 2018. Livingston and the others had argued that allowing drug offenders the opportunity to face a parole board didn’t change anything about their original sentences — it only meant that they could now serve their sentences through supervised release, not in a prison cell.

In the spring of 2020, the Missouri Supreme Court took up the argument but disagreed with the drug offenders. Parole, the court ruled, was an essential part of an inmate’s sentence and could not be tinkered with retroactively if the law was later changed.

It was another devastating blow. However, before Livingston could be sent back to prison, Governor Mike Parson stepped in, commuting Livingston's sentence to a form of modified house arrest. It meant Livingston stayed free.

But he had already lost so much. His father and mother had died while he was in prison. Even today, his grief is mixed with anger at the system that "pulled the rug out from under me."

“It was a shame,” he adds. “I still get so mad when I think about it.”

Livingston’s anguish isn’t unique. Since 2013, the RFT has interviewed and featured multiple drug offenders who experienced similar whiplash as they were informed, sometimes months after their trials and sentencings, that they were not eligible for parole.

Aside from Livingston, the RFT uncovered dozens of drug cases where the original arrests took place prior to 2017. In some instances, the slow pace of the legal system meant the defendants didn’t face sentencing until years after the fact, at a time when newly arrested drug offenders — and even prior offenders — could rely on being parole eligible after serving a percentage of their total sentence. Not so for the pre-2017 crowd.

Instead, many of these cases involve people who had been arrested while they were already on probation for previous drug crimes. Even if a new crime didn’t involve drugs, the arrest would trigger the full sentence of the previous drug cases — and, according to Missouri law, the sentence must be determined by the law as it exists at the time of the offense.

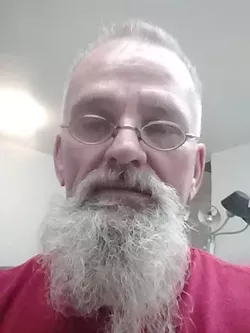

But time isn't a resource these drug offenders have to spend. Now 61 years old, Livingston is trying to rebuild his life as a retiree. He says he’s living off disability payments related to an old back injury, though he chafes at the restrictions of the “modified” house arrest that requires he wear an ankle monitor and maintain a curfew.

Of course, Livingston also recognizes how lucky he is, as hundreds of offenders convicted before 2017 remain in prison without hope for parole or a chance to demonstrate their rehabilitation.

That is starting to change, but slowly: To date, Parson's administration has paroled eight “prior and persistent” drug offenders. Livingston’s case is the only one whose conviction took place after 2017.

“I pray to God that they keep happening,” he says of the governor’s commutations. “There's a lot of people in prison shoved in that hole. They really don't deserve that much time.”