17 St. Louis Literary Cribs That Housed Great Authors

By Ryan Krull on Wed, Dec 20, 2023 at 6:00 am

So we present to you 17 great wordsmiths who have roots in, passed through or settled down in our fair city. Their rapturous descriptions of St. Louis can be enough to make us blush — although just as often they’re talking eloquent smack. We’ve also included info about the houses most closely associated with them — or at least the houses most closely associated with them that we could find still standing. (In some cases, this being St. Louis, the address leads only to a vacant lot.)

We hope the list inspires you to contemplate the streets where your favorite writers once lived. (Note that we intentionally chose writers who have been gone for at least five years, whether by death or moving van; it didn’t feel neighborly to send a flock of fans to, for example, Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Carl Phillips’ home.) If nothing else, we hope you can feel a little pride in St. Louis for having played — and for continuing to play — such an important role in American literature.

Credit goes to Lorin Cuoco and William H. Gass’ 2000 book Literary St. Louis: A Guide for providing key addresses for some of the writers on this list. And we have to give a shout out to all the people living in these homes who went above and beyond when a random reporter interrupted their already busy December. In reporting this feature, I remarked to one of the owners of William S. Burroughs’ boyhood home about how welcoming everyone had been when I showed up at this or that literary luminary’s old front door.

“I think that’s why we want to live in these places,” the Burroughs homeowner said. “Because we want to be a part of that history.”

Read on for more about the history — and the houses.

Central West End

Born in St. Louis in 1850, Chopin moved to New Orleans with her husband in her 20s but moved back to her hometown upon his death. It was here, in the final decade of the 19th century, that Chopin produced her best-known stories and her novel The Awakening, works considered scandalous for their depictions of women behaving badly by the standards of the day. In 1903 Chopin moved to the 4200 block of McPherson Avenue in the Central West End (shown above). Sadly, the following year she suffered a brain hemorrhage while attending the World’s Fair.

Webster Groves

Everyone knows that Smiley, who won the Pulitzer Prize for her novel A Thousand Acres, hails from Webster Groves. Less appreciated is the extent to which Webster and St. Louis as a whole have influenced her four-decade body of work. She tells the RFT that what made Webster a special place to grow up was that different social classes lived in close proximity to one another.

“Once I got old enough to walk around, I could see the fancy houses in Webster Park, the middle-class houses around Avery School, and the small, junk houses like the one my mother and I rented on St. John Avenue,” she says. “That got me interested in writing about all different classes — and races, since Avery School was peacefully integrated when I was in second grade.” The St. John Avenue house has since been torn down, but the house that used to belong to Smiley’s grandparents still stands tall not far away on Clark Avenue. (It's shown above.)

Later, Smiley’s family moved to a house on Wood Acre Road in Ladue, not far from the headquarters of the St. Louis County Library. “I used to walk to the library from the house on Wood Acre, pick a book off the shelf, and then lie down on the floor next to the shelf and read it,” she says. “I don’t know why they let me do that, but they did.”

Among other highlights from Smiley’s childhood include seeing shows at the Muny: Peter, Paul and Mary at Kiel Auditorium; and — most legendarily — the Beatles at Busch Stadium in 1966. She adds that she “probably wouldn’t have written” a number of her books had she not grown up here, including The Greenlanders (which fellow St. Louisan Jonathan Franzen called one of the best novels of all time) and her most recent, Lucky, which is due out in April.

Central West End, Midtown

In real estate terms, T.S. Eliot is most closely associated with the stately three-story brick home at 4446 Westminster Place in the Central West End. However, as outlined in Young Eliot: From St. Louis to The Waste Land, he only lived there for a year and was actually born at 2635 Locust Street, which was closer to downtown. In an unintentionally fitting tribute to a man whose best-known work is The Waste Land, that house is now a parking lot — not even a particularly nice parking lot, at that.

After moving from New Mexico to St. Louis, poet Dana Levin recently had some fun with the wasteland that is Eliot’s childhood home, with one section of a poem titled, “Standing Outside the Parking Lot That Was Your Childhood Home.” “It’s exciting to be living in the city that birthed / T.S. Eliot / even though he was a casual / anti-Semite/ like so many of his class and breed,” she writes. “I stand here DLev, / one of the roughs — aspirated, liberally / educated, / shtetl-fed.”

University City

T.S. Eliot is also name-checked in one of the all-time blistering depictions of our city, courtesy of Pulitzer Prize-winner Richard Ford. In Ford’s Reunion, the protagonist (who totally, for sure, definitely isn’t Richard Ford) bumps into an acquaintance with whose wife he’s had a liaison in the Mayfair Hotel downtown (which actually, totally was a real-life spot and is today the Magnolia Hotel St. Louis, above).

In that story, Ford writes that St. Louis is a “largely overlookable red brick abstraction that is neither West nor Middle West, neither South nor North; the city lost in the middle, as I think of it. I have always found it interesting that it was the home of T. S. Eliot and, only 85 years before that, the starting point of Western expansion. It is a place, I suppose, the world can’t get away from fast enough.” Ouch.

Ford does know a thing or two about high-tailing it out of St. Louis. After dropping out of Washington University’s law school here in the 1960s, Ford returned to the university’s English department as a visiting writer in residence many years later. The story goes that one of the writing program’s fiction students, a born-again Christian, sent him a note outlining what this student saw as many issues with his work. (The aforementioned philandering among them, perhaps?) That letter came on top of the fact that no students came to Ford’s office hours to seek his counsel, a situation that dismayed him. He packed up and drove off.

Is that story true? We couldn’t swear to its every detail, but it’s certainly true that it is a story.

Central West End, University City

Tennessee Williams left St. Louis when he was a young man and famously disdained the place for the rest of his life, bestowing on it the nickname “St. Pollution.” Not all that clever by world-famous playwright standards, if you ask us. But we’re the magnanimous ones here, throwing a very legit festival in his honor every year. During the pandemic, the Tennessee Williams Festival St. Louis even mounted his “memory play” The Glass Menagerie on a stage built to include the fire escapes of the Central West End apartment building where Williams once lived.

He shared that space (as well as another apartment in University City) with an abusive drunk of a father, which may to some extent explain his complicated relationship with the city. Today, the Williams family’s apartment at 4633 Westminster Place (depicted above) is an Airbnb, so you too can sleep under the roof that nourished genius.

And true Williams fans may want to make a second stop in St. Louis while following in the playwright’s footsteps. After dropping out of Mizzou, young Tom Williams took a job at the International Shoe Company downtown, the same firm that employed his hated father. Williams despised the factory job and eventually quit to enroll at Wash U, but his time there directly inspired the struggles of his Glass Menagerie protagonist.

The shoe factory today, of course, is St. Louis’ beloved City Museum — and so the building continues to spur the imagination of young people seeking to find their way. Only without, one hopes, the nervous breakdowns that Williams suffered as a cog in the shoe assembly line.

University City

William Gass did the opposite of ol’ Tennessee. Born in Fargo, North Dakota, he arrived in St. Louis in the late 1960s for a job at Washington University and hung around in the Lou long enough to become an institution unto himself. In 1968, In the Heart of the Heart of the Country established him as a serious voice in American fiction, but it’s Gass’ 1995 tome The Tunnel for which he’ll be forever remembered among that specific set of people who appreciate difficult, dense postmodern literature. If you’re into 652 pages of “endless coils of prose,” this is the book for you.

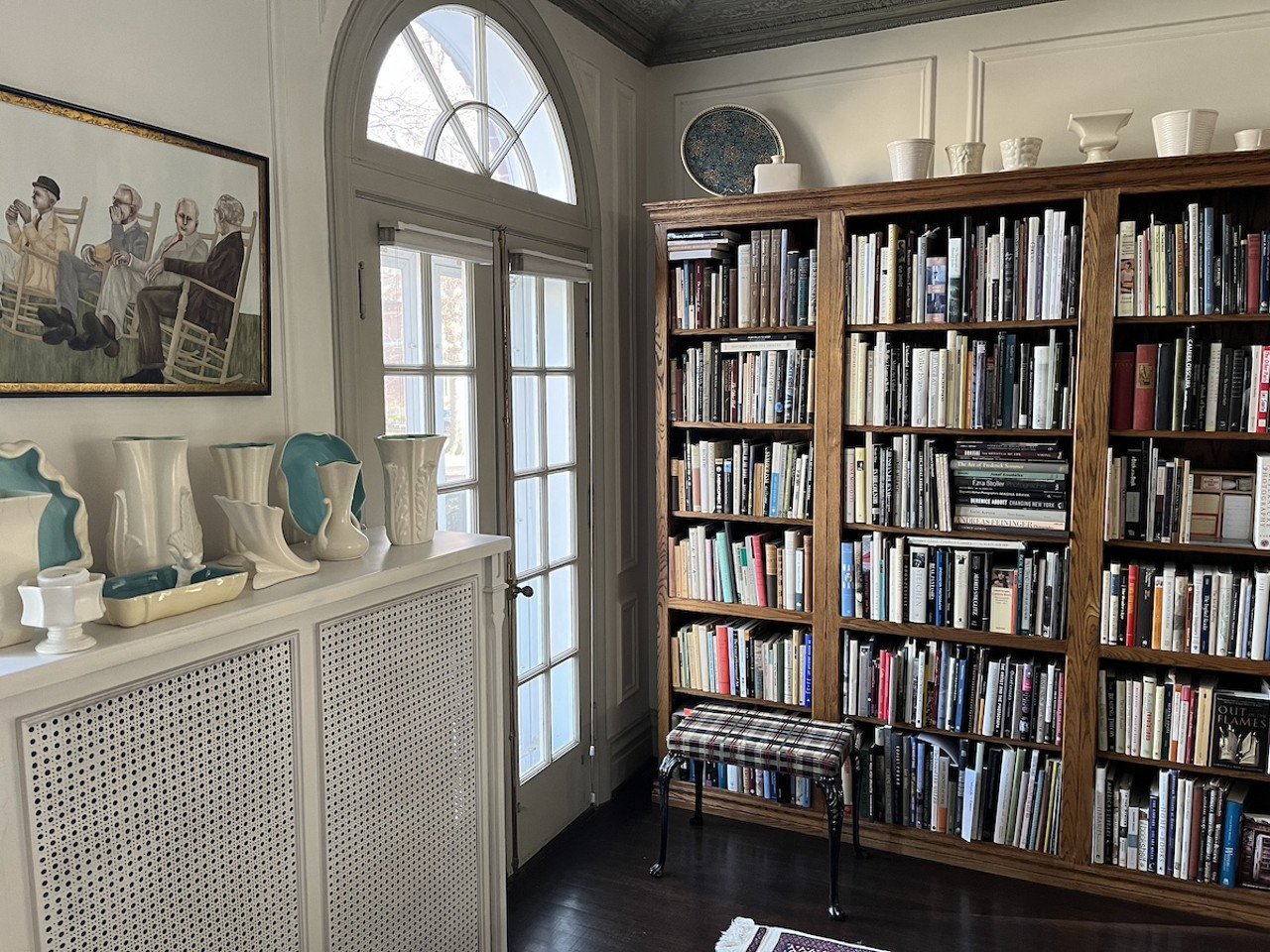

Gass and his wife Mary moved into their stately University City home in 1970. “It’s been a big part of our lives together,” Mary tells the RFT. “It’s the only house we ever lived in together. It always worked for us.” (Gass passed away in December 2017.) Though Gass had an office at Wash U, he did his writing at the home office, a second-floor study above the porch with windows on three sides overlooking the Limits Walk, which, prior to the construction of the Ackert Walkway, was the primary connector between the Loop and the university campus (shown in the photo above). Gass would often work with the windows open and pick up snippets of conversations coming from passersby. “He was sort of tickled every once in a while hearing a student talk to themselves or whistling or singing or something,” Mary recalls.

The interior of Gass' house is defined by books and bookshelves. As soon as the couple moved in, Gass set about building bookshelves in the house’s second-floor library, sourcing the wood and doing the construction of the shelves himself. When the Gasses’ twins moved out, their bedrooms were also converted to libraries, one for French literature and the other German.

Contrary to the stereotypes about the sort of people who write the kind of difficult books Gass did, the writer and professor didn’t take himself too seriously, at least if the following anecdote is to be believed: Gass once gave a lecture arguing a novel’s words were in fact true, and it was the readers who were the fictional entities. (It no doubt sounded more persuasive coming from Gass.) Some undergrad smart aleck only in attendance at the lecture for extra credit raised his hand and asked why he should care what some short man who may not be real had to say about reality. Gass was taken aback, but laughed. Then the whole crowd did, too.

University City

University City also features heavily in The Runaway Soul, an 835-page semi-autobiographical story by longtime New Yorker staff writer Harold Brodkey, who grew up in a three-story brick apartment building on Kingsland Avenue in the 1930s. The novel was hyped for years before publication but failed to meet those lofty expectations — however, it is probably more famous today for its flop status than it would have been had it been a hit.

A bit of a fabulist in his personal life, Brodkey claimed to have written his first published story “The State of Grace” in less than an hour, a physical impossibility. His body of work is replete with turns of phrase describing his hometown. “St. Louis swells out like a gall on the Mississippi River,” he wrote in a short story. “St. Louis is an island of metropolis on a sea of land.”

University City

When Brodkey came back to town during his New York years, he’d purportedly hang out with the local literati, among them Stanley Elkin, whom novelist Martin Riker called “one of the greatest writers of the 20th century.” Born in New York, Elkin grew up in Chicago and attended the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign before settling in St. Louis, where he was on the faculty at Washington University for three decades. His best-known story is probably the widely anthologized “The Guest,” centered on a traveling salesman/huckster who stays in St. Louis (University City, specifically) just long enough to get a house-sitting gig and get into antics.

In an essay titled “Why I Live Where I Live,” Elkin wrote, “The city of St. Louis is self-contained as an island, exists in no country, is, in a way, a kind of territory, gerrymandered as Yugoslavia, its limits fixed years ago, before the fact, staked out, one would guess, by a form of sortilege, a casting, say, of vacant lots, working farms and 19 miles of the Mississippi River into the equation…shaping a town like a stomach, stuffing it with ellipses, diagonals, the narrows of a neighborhood.”

A plaque adorning the backside of Stanley Elkin’s former home on Westgate Avenue reads “Stanley Elkin, 1967 -”, and the absence of a final year gives the sense that his energy still imbues the place. The current homeowners, a musician and a ceramicist, are certainly fitting stewards of that energy. The couple bought the home from an Elkin family trust after Stanley’s wife, Joan, an accomplished artist in her own right, died last year. The house came with two of Elkin’s books, including a collection of novellas, the first of which, Her Sense of Timing, takes place at the home.

“Oh, my God, this is my house,” the current owner says, recounting her experience reading that book. “It was crazy. I got such insight into the people who used to live here.” Another insight: Unusual for a city pad, the erstwhile Elkin estate has a kickass swimming pool.

The Gate District

Born in 1928 in what was then the Compton Hill neighborhood (now the Gate District), Maya Angelou is arguably St. Louis’ most decorated literary icon. Among her accolades are nominations for a Pulitzer Prize and three Grammys.

Angelou lived in this home until 1930, only to move to Arkansas and then return to St. Louis as an eight-year-old. In her seminal autobiography I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, she recounts her return: “St. Louis was a new kind of hot and a new kind of dirty. My memory had no pictures of the crowded-together soot-covered buildings. For all I knew we were being driven to Hell and our father was the delivering devil.” The trauma of that first year back in St. Louis would include Angelou’s rape and then the murder of her rapist at the hands of an uncle; Angelou then chose not to speak for five years.

The home has since been rehabbed and, in 2015, was given landmark status. The house itself still looks great, though it sits somewhat awkwardly in Saint Louis University’s ever-developing shadow.

Greater Ville, Webster Groves

Rachel Kushner never lived here, but the city would be wise to make some noise about its connections to the highly acclaimed author of Telex from Cuba, The Flamethrowers and The Mars Room. Fortunately, it isn’t too much of a stretch for St. Louis to claim the Oregon-born writer — at least a little bit — as our own. Her family has deep roots here. Kushner tells the RFT that her great-grandparents on her mom’s side ran Drosten Bakery, on north city’s St. Louis Avenue, where they also lived. Kushner’s grandfather, Fred Drosten, was to take over the bakery after graduating from Soldan High School, however he developed an allergy to flour which, combined with a scholarship to Washington University, sent his life on a different path. His future wife, Mary Lou, was a Webster Groves native who also went to Wash U and got a degree in architecture.

Their daughter, Pinky Drosten (also a Wash U grad: comparative literature), had her first date with her future husband, Peter, at Academy Barbecue on Academy Avenue, which Peter claimed had the best barbecue in St. Louis. In the 1960s, Pinky and Peter and their young family settled into a house in the Fairgrounds neighborhood at 4241 Prairie Avenue (now gone, sadly).

“On the corner of the street was a bar called Johnny’s Ghetto Lounge,” Kushner says of her parents’ old neighborhood. “Nearby was Sara Lou’s Kitchen, which sold frog legs and shrimp and was a favorite spot to eat.” (The building housing Sara Lou’s Cafe still stands, but like many north city landmarks, it’s owned by the city’s Land Reutilization Authority. It’s been considered a “place in peril” by preservationists for years now.)

Pinky and Peter often traveled across the Mississippi to the Harlem Club in East St. Louis, where they saw the likes of Ike and Tina Turner perform, treks that feature in the essay “Tramping the Byways” in Kushner’s book The Hard Crowd. Later, the family moved west to Eugene, Oregon, where Kushner was born. Kushner’s grandparents Mary Lou and Fred remained here, however, and young Rachel came back to visit every summer, staying with them at their house in the 900 block of Old Bonhomme Road in University City.

“I have fond memories, myself, of being taken by my grandparents to Miss Hullings Cafeteria many times,” she says.

Webster Groves

Webster Groves-native Jonathan Franzen has written three books that are (more or less) set in St. Louis: his debut novel, The Twenty-Seventh City; his memoir in essays, The Discomfort Zone; and his most-celebrated book, The Corrections, in which he disguised St. Louis as the fictional Midwest rust belt metropolis St. Jude. However, given the biting regard he showed for our town in his first novel, it’s probably best for everyone he used the pseudonym.

“Cities are ideas,” Franzen wrote. “Imagine readers of the New York Times trying in 1984 to get a sense of St. Louis from afar. They might have seen the story about a new municipal ordinance that prohibited scavenging in garbage cans in residential neighborhoods. Or the story about the imminent shutdown of the ailing Globe-Democrat. Or the one about thieves dismantling old buildings at a rate of one a day, and selling the used bricks to out-state builders.” We do make a fine brick.

However, it is worth noting that the National Book Award-winning writer was much warmer when writing specifically about the two-story brick, colonial-style home situated in a neighborhood just off Big Bend where he grew up — particularly in “House for Sale,” an essay about his selling the home in the wake of his mother’s death.

The house’s current owner tells the RFT she wasn’t aware she was buying the Franzen house until her sister-in-law typed the new address into Google Maps and “Jonathan Franzen’s boyhood home” popped up on the screen. The house on Webster Woods Drive is now substantially different from the one Franzen grew up in, she says, with an addition of a large family room and a primary suite expanding into what was once the backyard.

“I can only imagine what he’d say about it given his disdain for the changes he observed in the neighborhood upon a revisit 20 years ago,” she says. “But there are some remnants of his family remaining here too: Based on his essays, we know that the picture-frame molding in what was then the dining room, the brick walkway and the ’70s-era half-bath in the basement were all installed with pride by his parents.” One of the culs de sac in the neighborhood also has a greenspace at its center with a tree dedicated to the author’s dad.

After being inspired by her new digs to delve into Franzen’s oeuvre, the house’s current owner suggested her book club read The Corrections, which they discussed in the house itself. “I couldn’t help but visualize the characters — really, stand-ins for his parents — moving through the familiar rooms of our house,” she says.

Central West End

The original trust-fund hipster William S. Burroughs’ bust now stands sentry in front of Left Bank Books in the Central West End, just a few blocks from where he was born in a three-story, sturdy brick house in the 4600 block of Pershing Place, about a block from Kingshighway in the Central West End.

Burroughs’ life included wild stints in New York City, Mexico City and South America. Despite his itinerant life, he maintained a genuine emotional connection to St. Louis. He is perhaps the only person in its history who upon returning here fell into despair over how nice things had gotten. After visiting his hometown in 1965, he wrote in the Paris Review: “But what has happened to Market Street, the skid row of my adolescent years? Where are the tattoo parlors, novelty stores, hock shops — brass knuckles in a dusty window — the seedy pitchmen … Where are the old junkies hawking and spitting on street corners under the gas lights?”

Anyone new to Burroughs would be advised to start with his debut novel, Junkie, a work with an uncanny resonance in the midst of America’s current opioid crisis; just swap in the word “fentanyl” for morphine and goofballs and — if not for the dozens of other ways it would offend modern sensitivities and tastes — that book could be published today.

One description that has stood the test of time is Burroughs’ limning of the River Des Peres. In his 1976 memoir Cobble Stone Gardens, he describes our least favorite waterway as a place where “turds shot out into the yellow water from vents along the sides.” As true now as it was the day it was written, at least when it rains.

The current owner of the Pershing house says that she read Burroughs in high school, and even though his Beat style is no longer her cup of tea, she appreciates what he and other writers of his generation did to move the country forward in certain social aspects. Also, every time anyone in her family does laundry in the basement, they pass by an antique Burroughs Adding Machine, a proto-calculator invented by Burroughs’ grandfather whose success created the family wealth that allowed the Naked Lunch author to live a bohemian lifestyle, saving him from having to get a job like everyone else.

Central West End, St. Louis Place

Mark Twain is most closely associated with his hometown of Hannibal, Missouri, where he set his two most famous novels, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

But St. Louis is not without many Twain connections. He first came here by riverboat with his father when he was 10. Twain — who was of course then only Samuel Clemens — took to the city, and vice-versa. Clemens haunted the city’s rooming houses and piloted riverboats on the Mississippi to and from New Orleans. Later, as the world-famous Mark Twain, he gave lectures here, remarking that St. Louis was a place where “audiences are jolly, and where they snap up a joke before you can fairly get it out of your mouth.”

He often stayed with his cousin James Clemens on Cass Avenue in the St. Louis Place neighborhood. He spent an extended period of his late 40s here, researching and writing Life on the Mississippi, the book that Twain considered to be his finest. The Cass Avenue house stood as a city landmark until it sadly burned down in 2017. (The photo above shows it after the blaze.)

Twain’s sister’s residence downtown long ago was razed for Poelker Park. However, still standing is the home of his other cousin, JL Clemens, which is in the 3900 block of Washington Avenue in the Central West End.

That’s where Twain dined in 1902 upon his last visit to St. Louis, a trip during which he also attended a groundbreaking for the forthcoming World’s Fair. It is now a funeral home.

- Local St. Louis

- News

- Things to Do

- Arts & Culture

- Food & Drink

- Music

- Movies

- St. Louis in Pictures